Two years in review: Academic restructuring at the U of A

Two years in, where are we at with academic restructuring?

Emily Williams

Emily WilliamsOn the surface, the university seems to be thriving. Classes are back in person, the U of A has been performing better in global rankings, and there are more students on campus now than ever before. But underneath all those successes, the U of A is crumbling from the inside.

In the wake of academic restructuring, non-academic staff are trying to keep it all together.

Academic restructuring was first proposed in June 2020 by then-incoming President Bill Flanagan at a virtual town hall. Flanagan presented his plan for a “University of Alberta for Tomorrow,” just under a month before starting his term as president.

The plan was to reorganize the university’s faculties into groups over a two year period, to create a more financially sustainable model in light of unprecedented budget cuts from the provincial government. This resulted in a reduction of 1,050 staff positions, an anticipated drop in international rankings, and an overall feeling of uncertainty at the university.

A restructuring “must occur,” Flanagan said.

Restructuring was meant to pool administrative staff and resources, reducing administrative costs. Less resources to go around, meant more sharing of what remained.

Out of the different configurations presented, the college model was an effort to preserve the identities of different parts of the university. This was done by organizing faculties into three colleges: health and sciences, natural and applied sciences, and social science and humanities. Each faculty would be headed by an additional layer of administration: college deans.

The college model however, added more bureaucracy containing the highest number of senior leadership positions of all the proposals — a concern for some faculty. General Faculties Council (GFC), the governing body in charge of academic and student affairs, was not in agreement on whether the colleges required a senior leader.

GFC ultimately recommended the college model, with a caveat: no college deans. They approved a motion which recommended including a “service manager” who would report to faculty deans, as opposed to a college dean who would manage them. This recommendation was then overridden by the Board of Governors (BoG), the highest decision-making body at the U of A — meaning college deans would stay.

In a comment provided to The Gateway, Verna Yiu, interim provost and vice-president (academic), said that work is still being done to refine the college model.

“Since they were launched in summer 2021, work has been ongoing to define and operationalize responsibilities of the colleges. This past fall, a new operating model was released that articulated those responsibilities and authorities.”

Yiu said that an 18-month review of the model is underway and will be presented to GFC and BoG when complete.

At one of the final town halls before the 2020 BoG decision, Matina Kalcounis-Rueppell, the current interim college dean of natural and applied sciences, assured concerned students that they “will really not feel this organizational change in [their] student experience.”

So, just over two years later with the model now implemented, does this ring true?

Alexander Dowsey, a fourth year ancient medieval history student, says it does not.

Dowsey said the most prevalent impact of academic restructuring on his student experience was the loss of immediately accessible services. Previously quick and efficient processes were now taking much longer to complete, which could potentially derail students’ degrees.

According to a survey done by the Non-Academic Staff Association (NASA), academic restructuring left a profound impact on the quality of services. One respondent said that academic restructuring posed a “significant challenge to offering exceptional service.”

In March, Dowsey reached out to Arts Undergraduate Student Services (USS) for help in his BearTracks and received a response almost six weeks later.

“They told me I contacted the wrong administrative branch and had to go talk to a different branch, because they couldn’t do anything about it,” he said.

To say the current model is unsustainable would be an understatement. For those who are new to campus, trying to get help on top of long wait times can be a daunting and stressful task.

Dowsey’s mother is a history professor, so he’s familiar with the university’s resources and processes. Even then, he said that the process was grueling and long.

“I don’t think that’s ideal for our university. And it doesn’t speak to our administrative health that it takes so long to deal with relatively small requests.”

The feeling that services are now requiring extra steps, and extended periods of time, was also shared amongst many faculty members The Gateway interviewed for this article.

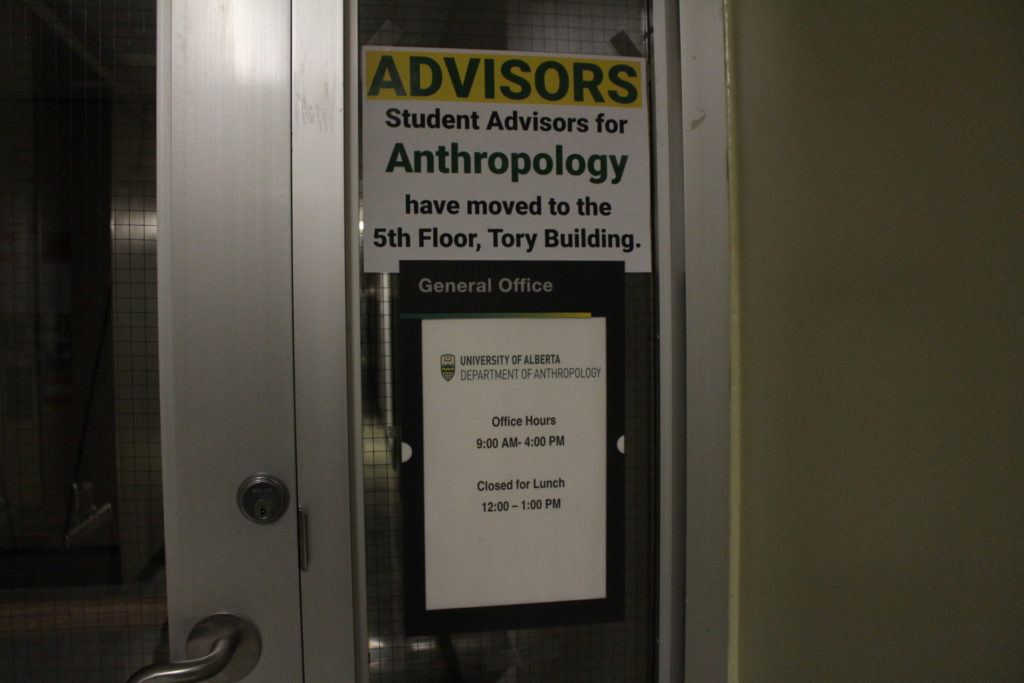

Marko Zivkovic, an associate professor in the department of anthropology, said that in the new model, oftentimes faculty don’t know who to ask for things. To illustrate his point, Zivkovic asked: how many people does it take to screw in a lightbulb?

“In the old ways, it was usually one or two. Now, we are talking about three, four, or more,” he said.

“I at least need to know who to ask, who may know who to ask, who will probably in the end know, who to ask really.”

“Whole environment changed” after academic restructuring

These extra layers of complexity are the result of centralized services. Many faculty had an administrator they knew well in the office next door who may have been laid off, relocated to another building, or are now working for multiple departments rather than one.

Laurie Adkin, a professor in the department of political science, talked about how COVID-19 exacerbated the effects of academic restructuring, as both events happened at the same time. Despite now returning to work in-person, the office is largely empty.

“The whole environment changed. We used to relate to people who had faces and names, and we knew who to go to if we had a problem,” Adkin said. “Those people are essentially gone.”

Now, in place of a team of dedicated administrators, faculty have been redirected to a staff service portal that operates on a ticket system.

Heather Coleman, a professor and an associate graduate chair in the department of history, classics, and religion, described the ticket system as “very clunky, compared to just having the name of somebody and emailing them.”

On the surface restructuring is nothing more than the addition of college deans, longer wait-times, and a new shared services portal. This may be an annoyance for some, but for non-academic staff, restructuring has been nothing short of a major overhaul of their lives on this campus.

“It was an ugly, embarrassing situation,” staff member speaks on fall contract delays

The Gateway spoke to a non-academic staff member, who works as an administrator, about their experience of working at the university after academic restructuring. Because of concerns regarding job security, The Gateway granted them anonymity, and will be using Jones as a pseudonym.

When academic restructuring was still in the planning and consultation process, there was lots of talk about creating economies of scale. By pooling the faculties into three colleges, the university was hoping to provide efficient and centralized administrative services for a fraction of the cost. Jones felt like this was anything but true.

I pity the people who are coming into this workplace. [They are] just making mistake after mistake and just having to swallow [their] pride and figure out how to not do it.

Jones, non-academic staff member

“That’s been a complete misnomer, almost an outright lie, because the only economies of scale that have been achieved [are jobs done] by two people [are] now being done by one,” they said.

To Jones, the processes are unstable. Either non-academic staff are doing jobs they are unfamiliar with, or they worry that jobs they used to be responsible for won’t get completed. Many tasks that used to fall to support staff have now been taken out of their hands, Jones said. As a result, many jobs go undone for long stretches of time, or they are done poorly.

For example, payroll functions and expediting contracts became centralized tasks. Initially, Jones had high hopes, since the spring and summer rollouts were so smooth. Very quickly, it became apparent that the job would not be completed on time this fall.

Prior to academic restructuring, payroll and contracts were handled at department level. However, the Shared Services unit has since taken them on.

Launched July 2021, the unit is a hybrid model of centralized and decentralized student and staff services at the university, currently operating online.

In the fall, contracts for positions that began September 1 were not issued until September 29 — leaving graduate students working for nearly a month with no contract. Several graduate student associations said the delays were the result of restructuring, and spoke out strongly against the process.

Despite working in “what had always been the normal time frames,” Coleman described the fall contracts as “the key problem” her department experienced with the Shared Services model so far.

“It was totally unacceptable,” she said. “The students were waiting to be paid, and it was just appalling.”

Non-academic staff watched from the sidelines as jobs they used to do were mismanaged.

“HR went way over capacity. Shared Services didn’t have enough people doing the job, they were working evenings, weekends. People were leaving, because the stress of it was so awful,” Jones said.

“It was publicized, a lot of students came out and talked about it, professors talked about it. It was an ugly, embarrassing situation.”

Whole academic restructuring process is “unnerving,” administrator said

According to Jones, the issues around contracts were just the beginning. They said they are deeply concerned, calling the whole process “unnerving.”

Although they can help each other, each person’s job is so different that another person can’t take it on, Jones said.

“That’s been a huge myth of this whole restructuring process.”

Administration across campus all do things in similar ways. But, the information and functions are specific to the department, and the people within them, who have been in their roles for years.

Now, those people are gone, and there are huge gaps left in their wake.

Despite having 10 years of experience working at the university, Jones said they feel as though they’re on day one of the job again.

“Together we make it work and we can pool our wisdom, but when a large segment of that wisdom pool is pulled out, the rest are scrambling and it’s very difficult.”

There’s been an effort to fill holes and gaps, but there’s not enough manpower to effectively train and still complete their workload. Jones said that a “sink-or-swim technique” was developed in lieu of training — new hires are just given a set of keys and passwords, and largely have to figure it out on their own.

“I pity the people who are coming into this workplace. [They are] just making mistake after mistake and just having to swallow [their] pride and figure out how to not do it.”

Ever since the cuts, Jones said many people tell them that they should be thankful they still have a job. Instead, they find it hard to see the positives.

“That’s a bittersweet thought, because you do get survivor’s remorse. You have to stick around and watch … processes and traditions that have been so robust and so good in the past, just completely decimated for no good reason.”

The feelings of staff are unsurprising when taking into account the scale of cuts the U of A received since 2019. The effects of lay-offs, retirements, and attrition are felt through the incredible workload of current administrative staff and the now-empty floors and offices where previous staff once stood.

Effects of managerialism have “demoralized staff”

Zivkovic spoke out against the managerial model that the university has headed towards.

“From what I can see, it has demoralized staff,” Zivkovic said. “And the demoralization is a part of the restructuring, because … what managerialism does is put people who know less in charge of people who know more.”

He said that supervisors are missing local knowledge and the only reason there has not been more breakdowns is because of the extra work being put in by existing staff.

“My worry is that you are overworking people, and paying them less to do more,” Zivkovic said. “And if they can, they will jump ship.”

Like Jones, Zivkovic felt this contributed to a loss of local knowledge. “And I think that’s one of the aims of restructuring: to make people interchangeable,” he said.

I don’t think we’re in it yet, but there is also a sense in which we’re on the verge of a death spiral of diminishing returns, in recruiting good students.

Marko Zivkovic, associate professor

The university hired a management consultancy firm called the Nous Group to assist in planning and strategizing restructuring. University of Sydney (U of S) hired the same firm during a similar restructuring process, with staff saying that the restructuring contributed to a decrease in the quality of education and experience at their institution.

Zivkovic said that when the same consultancy firm was announced, faculty knew “this is the worst case scenario” based on the results from U of S’s restructuring process.

“I personally find that it’s just insulting to our intelligence to have a very highly-paid management consultancy come in and tell us how to do things,” Zivkovic said.

Zivkovic quoted the book The Management Myth by Matthew Stewart to describe management consultancy firms:

“How can so many, who know so little, make so much, by telling other people how to do the job they’re paid to know how to do?”

Faculty anxious about direction university is headed, fear a “death spiral of diminishing returns”

Zivkovic said that the U of A will get through this.

“I’ll say that universities have been around for about 800 years, that we are obstinate and resilient people,” he said. “And so we will survive.”

“But whether you want to have an institution feeling that [it] is just surviving, is a different question.”

He described how there could be lasting negative impacts on the university as a result of this restructuring. “I don’t think we’re in it yet, but there is also a sense in which we’re on the verge of a death spiral of diminishing returns, in recruiting good students.”

He described this cycle, particularly in light of the university goal of increasing enrolment to 50,000 by 2026.

“If you want to have more students, you need to have undergrads, you need to have more teachers, and you need to have more graduate students to have [Teaching Assistants],” he said.

But the issue is that in order to attract graduate students, the university needs to offer more competitive funding, or more graduate courses.

“How do you attract graduate students if they look up the courses that are taught at graduate level and there’s precious few?” he asked. “That’s a death spiral for you.”

“Invisible ceiling” traps administrators in their roles, with no hope of promotion

Looking at the bigger picture, Jones expressed worry about the university’s future. For them, there are many feelings associated with academic restructuring: resentment, sadness, and complete distrust.

“[I feel] never ending frustration at the roadblocks that keep appearing in front of me. I just want to enjoy my work and enjoy my workplace as I did before.”

Because of academic restructuring, and the subsequent loss of so much knowledge, non-academic staff are now stuck in their roles. Jones said there’s no room for promotion, since they’re now too valuable to lose.

There’s no real reward for the work they’re doing, they said, and especially not additional monetary compensation. Jones described it as an “invisible ceiling” — they have the credentials, the expertise, and the knowledge to be promoted to better positions, but they just see other people take their place.

“We can just take what’s being delivered down to us. And notice all the holes in it as it comes down and know that it’s gonna be a bumpy ride, and just fasten our seatbelts and hang on with all the power we have to do.”

Despite all the difficulties, non-academic staff who care about students will continue to care. Eventually though, the student-oriented experience will be lost.

“If you’re someone on campus that’s worked with students and you’d like to work with students, you will do right by them. The university has to stand behind that more.”

When thinking about where the university is headed with this new model, Coleman said she feels worried about the sustainability of their work and their administrative staff.

“I’m actually quite anxious and I am not a negative person. I care.”

A review of the faculty of graduate studies and research in progress

Melissa Padfield, deputy provost of students and enrolment, told The Gateway that the faculty of graduate studies and research (FGSR) is currently under review. This faculty was not included in the original restructuring proposals.

FGSR is a faculty dedicated to providing support and services to graduate students.

“We’ve been pretty open, that we’re doing a review process of the faculty,” Padfield said. “And that’ll help to determine what our next steps are in terms of the FGSR structure and relationship to the new college model.”

Roger Epp, the current interim dean of FGSR, is meeting with deans and chairs about the review, but no formal consultation process has started, Padfield said. She told The Gateway that we could expect a lot more information in about three months.

“It would be talking about restructuring for [FGSR] so that it is able to be really effective within the new operating model and the new academic structures.”

Coleman said that this review is welcomed, as the faculty was not included in the original restructuring proposal and the faculty is “very hard to work with administratively.”

“I am delighted that they’re doing this,” she said. “One of the constant questions in fall 2020 was: why is FGSR not part of this process?”

Two years in, restructuring seems to have created a lot of anxiety for the university community. People are putting in more work, and have less resources, than ever before at the U of A. While it seems that the worst of cuts and restructuring is over, the impacts will continue to be felt as the university adjusts.

The U of A’s global rankings have started to recover from the downward trend seen in the wake of budget cuts. That said, many still fear that our university will not be able to sustain the same level of student experience, and academic success, that we had held previously.

The only thing holding the university together is non-academic staff. Even with a nearly doubled workload, they’re doing their best to maintain the same level of excellence students and faculty expect. But many are unhappy. If nothing changes going forward, the U of A could experience an incredible loss of invaluable faculty and non-academic staff, changing this institution for good.