Supplied

Supplied Diane Haughland and her team made a big discovery of some tiny species. Haughland is a taxonomist by trade, specializing in lichenology, and is an assistant lecturer in the faculty of agriculture, life, and environmental science (ALES) at the University of Alberta.

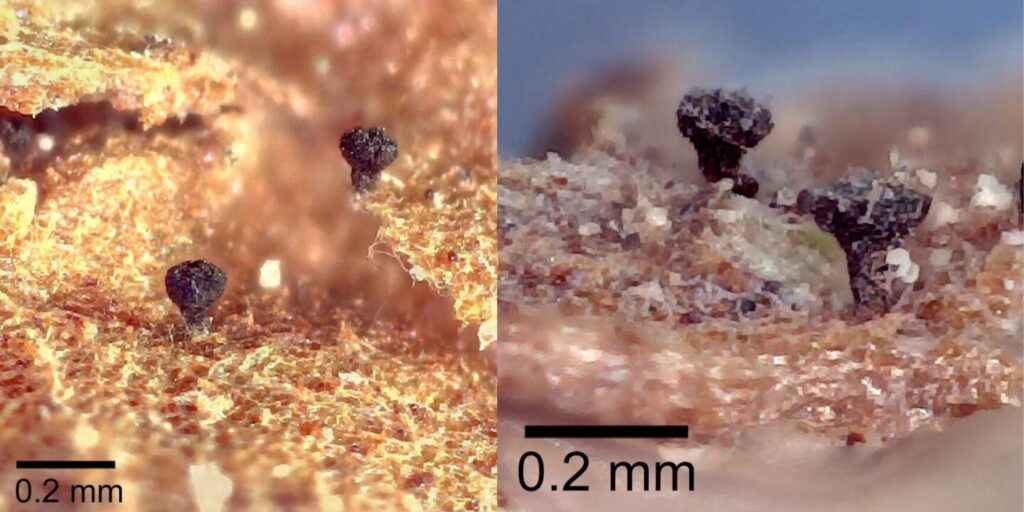

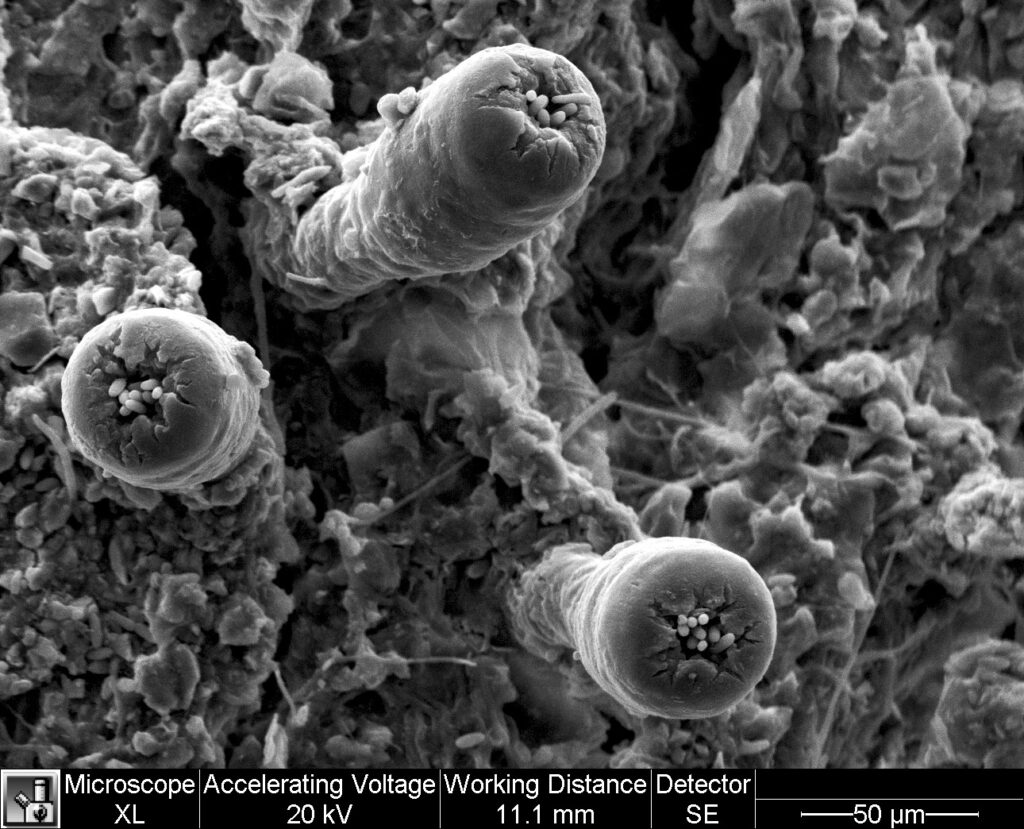

She was working as a lichenologist for the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute (ABMI) and was working to update the taxonomy of Alberta’s lichen when she and her team discovered new species of calicioids. Calicioids are very small, pin or stubble-like lichen and fungi.

“Nobody had really updated our taxonomy in probably 20 or 30 years so we’re working kind of from scratch,” she said.

They discovered 13 new species in Alberta over the course of the 13-year project. The aim wasn’t necessarily to discover new species of calicioids, but it didn’t entirely surprise Haughland.

“Big, hairy mammals, we think we know all the mammals that are in the province. We’re pretty good at knowing all the birds,” Haughland explained. “But as you get tinier in scale, there tends to be a higher rate of discovery.”

The size of these new discoveries range from being 0.2 millimetres tall to two millimetres tall.

They had teams of technicians across the province collecting samples. The teams would send back hundreds and thousands of collections that Haughland’s team would sort through. Discovering something so small, though, requires a certain technique.

“You know how people on the cover of a romance novel [are] staring off the horizon, in the distance? Kind of just insert a branch in that view,” she explained. “You don’t look right at a substrate, you kind of look past it and you’ll see these little stalks pointing up.”

“It’s always exciting to just figure out who our co-existing travellers are,” Haughland says

The new discovery of calicioid species shows Alberta’s biodiversity, but part of Haughland’s excitement isn’t purely scientific.

“It’s always exciting just to figure out who our co-existing travellers are,” she said. “I’m one species, but I’m just one species, and I really love to honour the other things that I co-exist with in this province.”

“Particularly in urban and parkland areas. We tend to underestimate how many fascinating things live around us,” she added.

For Haughland, these other species have inherent value, having evolved over the last “many millions of years.”

But the function of stubble fungus is relatively unknown from an ecological perspective.

“They have a tiny biomass. We don’t think that they’re harming plants in any way that they’re growing on. They may be helping with some decomposition, they may be providing a tiny food source for some other tiny critters. But in general, I just think they’re really fascinating.”

She also noted that the presence of stubble fungi tells her something about a habitat. When there’s more stubble fungi and lichens, the habitat is usually more interesting and it’s been around for longer. More variation in microhabitats also points to a richness.

And for her, that’s worth preserving.