Wintering Bees

Ab Sch

Ab SchWintering Bees

Written by Josh Greschner

Photos by Kevin Schenk

Video by Oumar Salifou

Gerard Sieben, a commercial beekeeper of over 40 years, usually wakes on winter days before the sun rises.

“If I’m melting wax, I have a schedule,” Sieben says. “If I start at 8 o’clock then I have to switch (barrels) at 8 o’clock every day. If I’m not melting wax, it doesn’t matter when I get up.”

Sieben is 63 years old. He has white hair, sideburns, enormous arms and hands like bear paws. He calls his beekeeping operation Apiaries of Alberta Pride. On his acreage 40 km outside of the city and 1 kilometre north of Highway 16, he must, in addition to melting wax in the mornings, shovel the snow from the concrete pads in front of his three shops and plough his driveway with a Bobcat.

“I do what I want to do,” Sieben says of working in the winter. Compared to the summer, he says “there’s no stress, there’s no push.”

Before spending the day repairing his machinery, Sieben sweeps the dead bees from the floor of a cold, temperature-controlled shop housing 450 beehives and approximately 9,450,000 live bees.

The art of beekeeping is the strategic manipulation of various components of a bee colony’s environment in order to yield products not limited to honey and wax. Bees produce honey by sucking nectar from flowers and, through a series of physiological processes that occur in individual bees and within colonies, evaporate the nectar into honey, which contains around 18 per cent moisture. Honey is a colony’s primary source of feed. Bees produce honey naturally, and methods in modern beekeeping cause bees to produce excess honey which producers harvest.

Summer is a beekeeper’s busiest season. As the season progresses, boxes called “supers” filled with nine frames of honeycomb, in which bees store honey, are placed atop hives. Standard beehives are usually at minimum two boxes high. Once the supers are full of honey, beekeepers manually lift the boxes from the hives, replace the full supers with supers containing empty frames, and return the full boxes to their farms. This process is called “pulling honey.” Full boxes can weigh up to 80 pounds, and given that Sieben’s 3,000 hives each produce numerous full supers, he says that pulling honey is beekeeping’s most laborious practice, even after vast technological and experiential developments from his early days when he worked with his uncle Len, a Catholic priest. In one of his first experiences pulling honey, Sieben’s bee suit was a parka and a cardboard box he wore on his head.

“I got the shit stung out of me,” Sieben says. He received an adrenaline shot from a nearby hospital and went back to work.

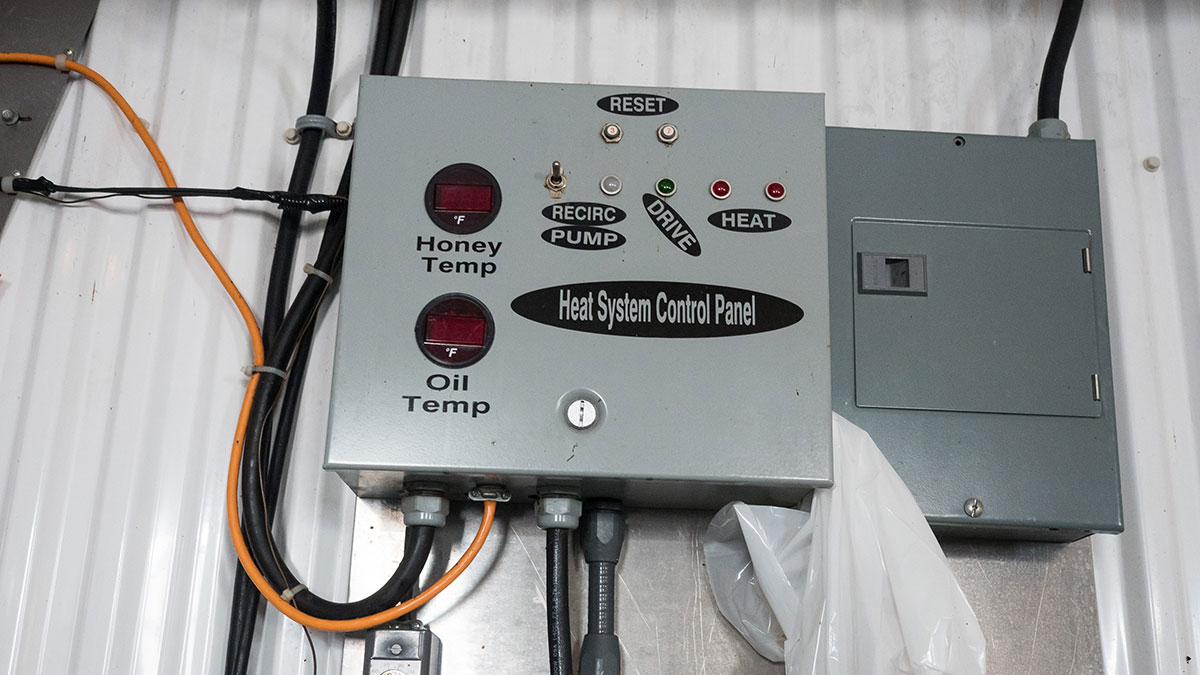

In what is called the “honey house,” individual frames full of honey enter a centrifuge called an extractor and honey is spun from the frames and pumped into storage tanks before being poured into barrels. Beekeepers often employ temporary foreign workers for the honey producing season, and from April to October, five Mexican beekeepers live with and work for Sieben. Commercial honey producers sell their honey to large companies such as BeeMaid. 2015 was an exceptional year for Sieben and he produced over 900 barrels of honey.

“When we’re shipping everything away, every load that goes out makes me smile,” Sieben says.

Sieben grew up on a farm in western Saskatchewan with seven siblings. Rather than finishing grade 11, he moved to Edmonton to weld truck bodies. He says he excelled at his job but it was repetitive, low-paying and unsatisfying.

“Alcohol and loneliness played a big part of it,” Sieben says. “You really didn’t know where you were going.”

In his mid-twenties, Sieben became interested in bees after he found out that Len and Len’s friend, Archie Demers, worked hives in the summer.

“I went out there one day and they were pulling honey and extracting. Archie had a building that had maybe 100 barrels of honey sitting in it. I did the math and he had about $35,000-40,000 of honey sitting there. And I thought ‘He’s going to do this how many times this year? And I’m working for $2.50 an hour? There’s something wrong with the way I’m thinking.’”

Sieben learned his craft from Archie, an all-around handyman who built his own hives and honey house. Archie was also an eccentric.

“He lost one eye, he cut a few fingers off building bee hives, and he had one old truck,” Sieben says. “I had a lot of good times with Archie. He loved to drink. The thing about him was that he never took life seriously.”

Honey production slows into September and beekeepers must eventually decide how to winter their bees. Until Canada closed its borders on bee imports in 1987 to prevent the spread of harmful mites, beekeepers in Canada would often kill their colonies at the end of the honey producing season and rebuild their colonies in the spring.

“We killed them with kindness,” Sieben says.

Rebuilding entire colonies was expensive, time-consuming, and made borrowing money from banks difficult because collateral had to be regenerated each season. Sieben’s first attempt at wintering bees was a failure.

“I put 250 hives in this building, built shelves, insulated the building, and what I had heard is you have to have a lot of air circulating because these bees use up a lot of oxygen, so I had two fans blowing in all winter. I went back in the spring and there were two hives alive. I took them outside in April and then they frickin’ died.” Sieben laughs. “It’s been a learning process ever since. I’m still farting around with it.”

Wintering (also called overwintering) is a series of processes that preserve bee colonies throughout the winter to prepare them for the following honey producing season. According to researcher Adony Melathopoulos (whose 2007 paper The Biology and Management of Colonies in Winter informs this paragraph) bees don’t hibernate; rather, they cluster in their hives when temperatures drop below 18 degrees Celsius in order to keep warm. Beekeepers must ensure that there is enough honey in hives for bees to feed on during the winter, and the cluster slowly inches from empty to full honeycomb in an upwards and sideways motion, never downwards. This movement, along with bees “pumping” their flight muscles, creates heat. Thus wintering bees relies on maintaining temperatures that are cold enough to allow bees to cluster and to consume a minimum amount of feed, but not so cold that bees must stay warm at the expense of feeding. Sieben finds that maintaining temperatures between -5 and 5 degrees best serves his purposes.

In order to conserve resources in cold temperatures, colonies produce winter-specific bees. It is generally known that summer worker bees have short lifespans, ranging from about 4-6 weeks. As early as mid-August, says entomologist Dick Rogers, colonies begin producing winter bees that can live 4-6 months. It is dead winter bees that Sieben sweeps from his shop floors.

There are two primary methods beekeepers use to control the temperature of their hives during prairie winters, and Sieben uses them both. The first is temperature-controlled interiors. Fans activate at relatively high outdoor temperatures to cool the space while interiors effectively protect from extreme cold. Sieben’s space can hold 800 hives but he chose to house only 450 this year because of the mild winter. His remaining hives are in farmers’ fields wrapped with insulated tarps and topped with fastened plywood to prevent moisture from seeping into the hives and to protect them from strong winds. Outdoor wintering has the advantage of allowing bees to fly outside their hives on warm days and defecate during what are called “cleansing flights.” Bee excrement looks like small brown spots.

“If you don’t know it and you got your car parked close by, they’ll shit all over it,” Sieben says. “The snowbanks are brown. A lot of people don’t know that or they wouldn’t be letting us put our bees where they are. That’s nature, man.”

Another wintering option for beekeepers is to transport hives to warm regions with flowers; popular destinations for Canadian bees include the Fraser Valley in BC and in Ontario’s Niagara region to pollinate a number of fruit flowers including blueberries, cherries and raspberries. Pollination is the stimulation of fruit production in plants. When bees gather nectar and pollen for their hives, additional pollen sticks to their hairy bodies which they disseminate into numerous other flowers. Earning pollination contracts can be lucrative and Sieben says that they can pay beekeepers around $140-150 per hive. Sieben used to pollinate in BC’s warmer regions but he admits that hauling his bees halfway across the country is no longer worth the trouble.

Winter bees die off as the weather warms in March and April, and after mass cleansing flights, hives that remain alive after the wintering period are ready for spring flowers. Colonies dying in the winter is inevitable, and winter losses have been higher in recent decades than they have in been previously. Spring is nonetheless Sieben’s favourite season.

“It’s like opening up Christmas presents. You’re curious to see if your work paid off. Some days you’re going to come in happy and other days you’re completely pissed with yourself. When I can come home and say ‘I opened up 300 hives today and I found 20 dead ones,’ it’s great. But if I come home and open 300 hives and I find 20 live ones, it’s not a very good time of year.”

Although Sieben has extensive beekeeping experience, he avoids complacency because of beekeeping’s dynamic nature.

“If you ever think you figured it all out,” Sieben says, “it’s going to bite you in the ass.”

Beekeeping has been complicated in the past few decades as a variety of bee diseases and pests have not only been discovered by researchers, but covered in the media. Some of the most common afflictions to bees include verroa mites, which feed on the haemolymph (essentially the blood) of bees and make bees susceptible to a virus that deforms wings; American and European foulbrood infects and kills bee larvae; nosema is a parasite that causes bees to defecate in their hives and eventually die.

The most publicized threat to bees is colony collapse disorder, in which bees disappear from hives with sufficient brood and feed but without the microbiological causes of verroa or nosema. The condition has been mysterious to researchers and a serious cause for concern among beekeepers, specifically in regions of the US and Europe. Hive mortality rates have been exceptionally high in the past decade, but according to a 2010 paper by Geoffrey R. Williams et al., colony collapse disorder is too often speculated to be the explanation of dead colonies. Meanwhile, apocalyptic language (“bee holocaust”) stimulates the public’s imagination. Yet in 2009, American beekeepers rated the threat of colony collapse disorder as the eighth most important contributor to hive mortality.

Researchers also examine other threats to colonies such as small hive beetles (which feed on pollen, honey and brood, and secrete slime), neonicotinoids (insecticides) and various viruses. Nonetheless, beekeeping and honey production in Canada has thrived. Statistics Canada reports that the total number of colonies in the country has increased from 592,120 in 2009 to 721,106 in 2015, and honey production, while fluctuating, has increased in a general upward trend from 70 million pounds in 2000 to 95 million pounds in 2015 (2006 saw Canada produce over 100 million pounds while the next two years didn’t see 70 million). Alberta has the most hives in Canada and has been Canada’s top honey producer for decades.

Furthermore, beekeepers and honey producers occupy a singular position in our cultural consciousness. They are fundamentally farmers, but beekeepers aren’t typically associated with greed and environmental disregard as livestock producers sometimes are, and arguments about the ethical treatment of animals don’t apply to beekeepers. Beekeeping is seen to be a leisurely activity which retirees or free spirits perform often with a kind of mesmerized love for their bees. After knowledge of diseases became widespread, connotations of vulnerability and fragility in beekeeping followed, and the stereotype of the victimized, financially unsound “poor old beekeeper” appeared. Sieben says beekeepers play the stereotype to their advantage — for example, driving nice new trucks into farmers’ yards is inadvisable, even though a beekeeper can often make more money off a farmer’s property than a farmer can.

Sieben’s attitude toward diseases and pests, many of which can be eliminated with practical solutions that require diligence, organization and hard work, is the same attitude he had after his first wintering attempt: beekeepers must adapt.

“We’re learning a lot more,” he says. “Definitely, if a guy closed his mind and said ‘I’m not going to treat,’ he would disappear.”

Sieben returns to his newly-renovated home after checking his wax melter, his hives, and the temperature of his cold room. His wife Kathy usually cooks for the two of them but Sieben often insists on preparing chicken — rather than laying a chicken flat in a pan, he sits the chicken up as if the pan was its tub and stuffs the chicken’s skin with discs of onion.

“There’s Johnny,” Sieben says, referring to his creation.

“There’s Howdy Doody,” Kathy says.

After dinner, he watches the Oilers, of which he has multiple opinions. For the first time in his life, evenings are a time to relax.

“When I turned 60 I quit working evenings,” Sieben says. “Most of my life I worked 7 in the morning to 11-12 at night. For a lot of it too, I worked full time and kept a part-time job and kept bees on the side. I did the two to keep one going. It got to a point where bees started making more money than anything else and finally, you kept rolling the money in. It came to a point where it looks after you.”

He puts his arm around Kathy.

“If you’re fortunate enough to know what you want when you’re 20, you’re lucky. But most people look back and say ‘This is what I am now’ and don’t know how the hell they got there.”

Sieben seems to remember how he got to where he is, but it’s the task of Kathy, his two sons and their wives, his grandkids and his extended family to get the stories out of him. He’ll continue making stories because he isn’t interested in retiring. In the upcoming years, he plans to work as many hives as he does now, if not more.

“You never retire,” Sieben says. “Even guys that retire still fart around with bees.”

“He’s going to keep going until he can’t do it anymore,” Kathy says.

“I don’t know how anybody retires,” Sieben says. “What are they going to do? Sit in a corner and watch every nickel? You might as well be working.”

In spite of his youthful boasts (Sieben convincingly advocates for the rejuvenating effects of daily honey consumption), age slows him to the pace of wintering bees.

“I usually don’t last past 10 o’clock,” Sieben says, sleepily.