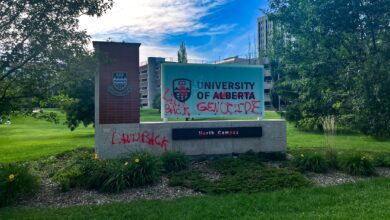

Reconciliation in health care is essential for Indigenous communities, U of A professor says

When looking to the future, Dr. Lafontaine expressed the need for concrete action past "performative" statements.

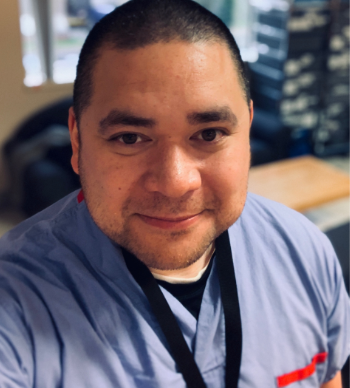

Supplied

SuppliedA University of Alberta professor has expressed the need for proper reconciliation to address the inequalities faced by Indigenous communities in the Canadian healthcare system.

For Dr. Alika Lafontaine, associate clinical professor in the U of A’s faculty of medicine and dentistry and recent president-elect of the Canadian Medical Association, reconciliation is essential to provide Indigenous communities with proper health care. He expressed the need for proper education on the historical medical mistreatment of Indigenous communities, alongside concrete steps towards addressing current inequalities.

Dr. Lafontaine described the COVID-19 pandemic as showing Canadians “a sliver of the challenges that Indigenous peoples face day-to-day.” He described the current limited access to health care facilities and proper patient care as comparative to the care Indigenous communities have received for years.

“The fact that there’s not enough health care workers to provide services we’ve come to expect, not having facilities available near the places where we live, and not being able to have that visit or follow up with your physician… all of these things are comparative to what Indigenous peoples have experienced, for a much longer time, in a much more magnified way,” he explained.

According to Dr. Lafontaine, pre-existing inequalities contribute to some of the reasons behind the disproportionate effect COVID-19 has on Indigenous communities. He also noted that Indigenous communities are subject to vaccination inequalities, something he attributed to previous mistreatment in the Canadian health care system.

“One of the busiest and the most notorious Indian hospitals was actually just outside of Edmonton — the [Charles] Camsell Hospital,” he said. “If you look at the history of Indian hospitals, which isn’t as well known as residential schools, autonomy wasn’t respected. There were laws in place where if you were told to go to the hospital, and then you left the hospital without the consent of being signed out by your provider, you [could] actually go to jail. It was actually illegal to make any of those choices yourself.”

“The average Albertan resident will sit back and shrug their shoulders and say ‘what’s the big deal with the vaccine,'” Dr. Lafontaine described. “When you look at the history of Indigenous peoples in Alberta… it is logical to see how [vaccine mistrust] would extend into the experiences of [Indigenous] patients within these institutions.”

According to Dr. Lafontaine, the inequalities faced by Indigenous peoples amplify the need for addressing historical trauma within Indigenous communities.

“When you look at vaccination in the time of COVID-19, it illustrates why dealing with that trauma is so important in ensuring that there’s a response from the system that accommodates people’s lived experience, but also understanding how approaching Indigenous communities with vaccination is quite a bit different than approaching your average residency and in an urban city like Edmonton or Calgary,” he said.

When looking to the future, Dr. Lafontaine expressed the need for concrete action past “performative” statements.

“There’s a difference in me saying ‘I’m going to provide care’ and actually providing the care,” he said. “We are starting to see growing calls for a shift from talking about what needs to be done to actually doing it.”

For non-Indigenous individuals, Dr. Lafontaine recommended using the National Day of Truth and Reconciliation to educate themselves on the histories of Indigenous communities. For those in healthcare, he suggested being intentional in making safe spaces for Indigenous patients.

“Get yourself educated about what happened with Indigenous history… and for those in medicine, we have the opportunity to change the ways that we treat Indigenous patients, and the spaces that we make available for them,” he said. “There’s ways that we interact with each other that we can change in the moment. That’s the starting point that I encourage non-Indigenous peoples to think about, especially on this National Day of Truth and Reconciliation.”