Gregory F. Funston, Tsogtbaatar Chinzorig, Khishigjav Tsogtbaatar, Yoshitsugu Kobayashi, Corwin Sullivan and Philip J. Currie

Gregory F. Funston, Tsogtbaatar Chinzorig, Khishigjav Tsogtbaatar, Yoshitsugu Kobayashi, Corwin Sullivan and Philip J. CurrieWhen Gregory Funston took his first trip to Mongolia in 2014, he didn’t know what adventure the next few years would bring. Flash forward six years and he’s published findings from that trip.

University of Alberta alumnus and current Royal Society Newton International Fellow at the University of Edinburgh’s School of GeoSciences, began his journey in palaeontology began much earlier at the young age of four or five when he watched a documentary on the National Geographics Channel about digging dinosaurs in the Gobi Desert. Combined with summer camp experience at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumheller, Alberta the young boy was spurred to pursue his dream of becoming a paleontologist.

“I often call dinosaurs the gateway drug to science because for a lot of kids, the first exposure to science is through how we understand dinosaurs,” Funston said.

Less than 20 years later, as part of his PhD project, Funston flew to Mongolia with his supervisor Phillip Currie, a renowned Canadian paleontologist and professor at the U of A, to study dinosaur specimens related to those found in North America. As a learning exercise, Funston was assigned to analyze some specimens which recently came to their team.

“[Currie] essentially showed me this bucket of bones and said these are closely related to what I was working on,” Funston recounted. “Maybe I would learn a little more about these groups by working on these skeletons.”

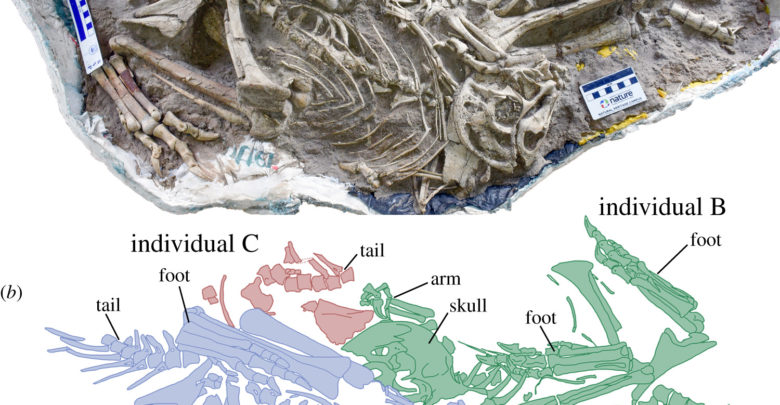

Many specimens were brought to Funston, but one truly caught his attention — a fossilized block and a skeleton from the same assemblage which contained three dinosaurs buried together.

“Every moment that I was sitting in the room working on this specimen was surreal because these are the best fossils I’ve ever worked on,” Funston exclaimed. “Not many paleontologists get the privilege of working on such excellent materials.”

After extensive work on the specimens and comparing them with already known animals, one major difference stood out: the hand. Oviraptorids, the group to which this dinosaur belongs to, have three fingers on each hand. However, this particular specimen seemed to be missing a third finger.

At first, this was seen as the result of millions of years of mother nature wreaking havoc or lack of care at the excavation site. But, further digging revealed otherwise.

“I excavated [another hand] from the main block and was able to confirm that what we thought initially was damage to the third finger was actually that there was no third finger,” Funston said. “Instead there was this stub at the end that wouldn’t have been able to make a joint.”

The find was a two-fingered oviraptorid. Unlike many well-known dinosaurs which are big, fierce and toothy, this oviraptorid was small, weighing about 75 kg, and also displayed a toothless beak. Covered by plumage, it is comparable to a modern-day cassowary, a large, flightless bird native to Southeast Asia and Australia.

However, how these oviraptorid specimens were collected is the real story.

“These specimens were poached, which means they were collected illegally by non-professional paleontologists and this is a really big problem in Mongolia,” Funston explained.

In 1998, a famous Tyrannosaur skeleton, Sue, was auctioned off for $8.36 million dollars and ever since then, a steep price has been placed on dinosaur fossils. Funston says that this has led to nations such as Mongolia, which have rich fossil reserves and high amounts of poverty, experiencing augmented occurrences of fossil smuggling. Unfortunately, this means that these specimens become lost to science.

“We’ve lost a lot of contextual data about how they were preserved together,” Funston explains. “Excitement is one of the main emotions … but there is a bitter-sweet disappointment when you think about what we could have known if it had been collected by us.”

In honour of the way it was discovered, this dinosaur was given the name Oksoko avarsan. Oksoko is a triple-headed eagle from the mythology of the Northeastern Asian area, representing the three skulls found together and avarsan is the Mongolian word for “rescued,” paying homage to the way the specimens were confiscated from poachers and to the numerous fossils every year that are lost to poaching.

“One of the things that I have been trying to emphasize … on this project,” Funston asserts. “Is the aspect of poaching and how detrimental it is to science to have fossils looked at as commodities rather than as part of our shared heritage”