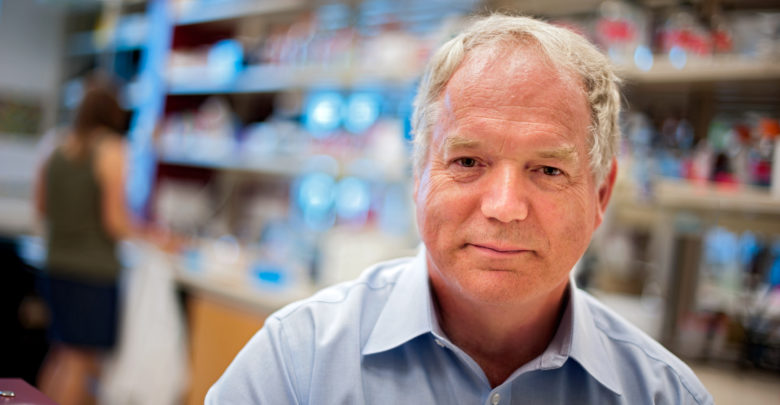

Richard Siemens

Richard SiemensWith the first win dating back to 1923, a University of Alberta researcher is the second Canadian to receive a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Michael Houghton, U of A Canada Excellence research chair laureate in virology and Li Ka Shing and department of medical microbiology and immunology professor, was awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for discovering the Hepatitis C (HCV) virus and subsequently working on a vaccine.

Houghton discovered the virus previously called non-A non-B hepatitis, in 1989 while working at American biotechnology company Chiron. He joined the U of A in 2010 as the Canada Excellence Research Chair in Virology in the Li Ka Shing Institute of Virology, where he began researching a vaccine for the disease.

“It’s a great honour and a great pleasure to receive this prize as a member of the University of Alberta,” he said regarding his award.

For Houghton, it was his passion in medical research that fuelled his discoveries.

“We have a duty to address unmet medical needs at the research level and at a medical level, and that’s what Lorne and I are trying to do at the Li Ka Shing Institute of Virology.”

It was D. Lorne Tyrrell, the founding Director of Li Ka Shing Institute of Virology, who actually informed Houghton of his win after the winners were announced at 3:30 a.m. on October 5, 2020. Houghton, who is currently in California, was woken by a call from his long-time colleague.

According to Tyrell, Houghton’s discovery 31 years ago revolutionized the safety of blood exchange. In the 1980’s, thousands of Canadians were infected with hepatitis C from infected blood products. Houghton not only named the virus but also developed a way to test blood for it.

“Everyone in Canada should be so grateful to Michael because he was the one who discovered the virus that caused the tainted blood scandal that hit Canada very hard,” he said. “This discovery was accompanied by developing diagnostic tests that have made blood safe for the whole world.”

“Canada is so very proud to have their second Nobel Prize winner in Physiology and Medicine, the first one being [back] in 1923. We’ve waited a long time.”

Vaccines necessary to prepare for future impending virus pandemics, Nobel Prize winner says

Houghton came to the U of A to collaborate with Tyrrell to create a vaccine for HSV. Fast-forward ten years and the vaccine is currently in pre-clinical trials — the phase right before human testing.

Highlighting the consequences of COVID-19 and HCV, killing around 1 million and 400,000 people respectively, Houghton emphasized that viral infections need to be met with a corresponding vaccine. Currently, Houghton is working on a COVID-19 vaccine.

“These viruses are a permanent threat and we need diagnostics, anti-virials, and a vaccine — we have to have a vaccine stop pandemics,” he said.

“With the COVID epidemic underway, all governments and all citizens around the world are now well aware that we can have these terrible epidemics… I think COVID has taught us that we need to be better prepared in for the next pandemic because it will come.”

Though multiple effective anti-viral drugs exist to treat HSV, Houghton said it’s not enough to prevent the spread of disease.

“Diseases like gonorrhoea, syphilis, and chlamydia — we’ve had cheap drugs available for decades, and yet we still have big epidemics of those diseases.”

Houghton believes the current vaccine will be able to treat all different versions of HSV around the world. He’s also optimistic the U of A can create enough vaccine in-house to treat at HSV-risk populations in Canada such as intravenous drug users. This move can prevent the Canadian government from spending $1 billion dollars to treat new patients through anti-viral drugs.

“We believe we can prevent the transmission of 90 per cent of cases from vaccine produced at the University of Alberta,” he said. “Not only will that stop a lot of suffering…. but it’s going to be cost-saving to the country.”

Houghton’s Dad wanted him to become an accountant

Born in England, Houghton studied physics, chemistry, and math in high-school.

Unsure of the career path he wanted to take, he ignored his father’s suggestion to become a charted accountant and took a trip to a reference library where he spent a week combing through the career section of books.

After reading a book on microbiology and Louis Pasteur — renowned microbiologist — Houghton knew what he wanted to pursue.

“It was a very wise decision to not become a charted accountant because I still struggle with me taxes these days,” he joked.

“I picked up a book on Louis Pasteur… and I realized that’s for me — that’s what I want to do.”

Reading this book on Louis Pasteur launched Houghton into his career and he attended the University of East Anglia, one of the few schools not requiring a high-school background in biology. He went on to get his PhD at Kings College at the University of London studying virus transcription.

From his start at that library to being a Nobel Prize winner, Houghton has taken away one main piece of advice for for current science students: find what you’re passionate about.

“You gotta figure out what you really want to do in life,” he said. “For some students, it’s making money — if that’s your passion than do it.”

“I honestly believe students need to find what they’re really motivated to do because if you have that passion, you’re likely to be successful and to have an enjoyable life where you can contribute to society.”