supplied

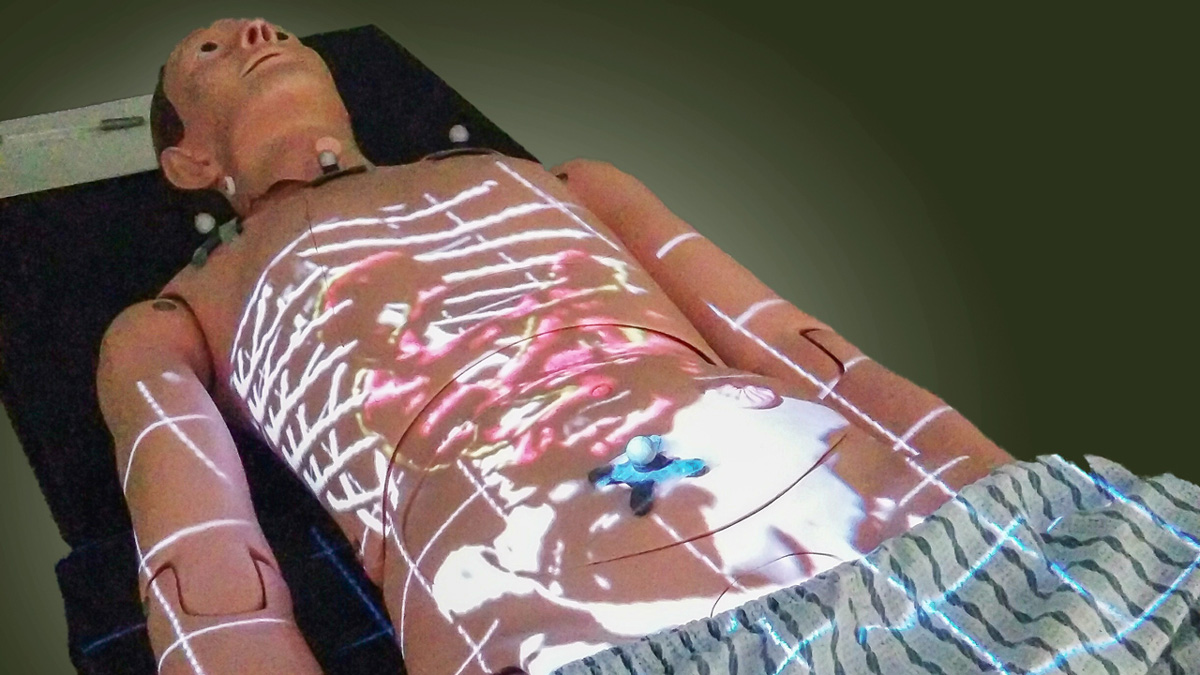

suppliedNew technology being developed at the University of Alberta could allow surgeons to project patient’s internal anatomy onto their body during procedures.

This is only one of the potential applications for ProjectDR, a system created by Ian Watts, a third-year computing science graduate student. ProjectDR is an augmented reality technology that allows projection of images onto an object. It uses a motion capture system to track landmarks on the object and adjust the image displayed from the projector in case of movement.

Watts’ original idea was to create a handheld projector able to accurately display images in one location even as the projector was moved. What began as an undergraduate class assignment over four years ago has now evolved into a technology that is currently being tested in pilot studies for teaching chiropractic and physical therapy procedures.

The development of augmented reality technology in medicine has garnered significant interest in recent years, Watts said. However, he said ProjectDR has features that set it apart from other technologies, such as augmented reality headsets like the Microsoft Hololens.

“The reason (we chose) projection is that it gets hardware out of the way,” Watts said. “It doesn’t have to be cleaned and it isn’t suspended on anybody’s head, so there’s nothing interfering with the interaction (with the patient).”

The first application of ProjectDR aimed to aid chiropractors. Since natural variation amongst patients, fused or extra vertebrae and injuries make this job error-prone, knowing exactly where to focus would greatly benefit this type of treatment, Watts said.

“Having the medical images displayed on (patients’) backs means you don’t have to spend so much time doing something invasive like poking around,” he said, “You can instead immediately find what you’re looking for.”

Another application for ProjectDR is in surgical planning, where preoperative images, such as CT-scans and X-rays, would be displayed on a model or directly on the patient. Here, infrared markers are placed on patients and lined up with markers on the images so that if the patient or surgeon moves, the motion capture system will adjust the projection.

Different layers could also be projected during surgery, such as the ribcage first, then the heart and major blood vessels, allowing the surgeon to avoid these, and finally the organ of interest. It could also help when the patient is at an angle different from the perspective the pre-operative images were taken from, such as lying on one side.

Laparoscopic surgery, a procedure where a camera and tools are inserted through small ports on the patient, could also benefit from this technology, Watts said. In this case, ProjectDR would allow surgeons to project the position of the tools in relation to the organs by tracking the tools.

Although the technology isn’t quite ready for surgical applications, Watts said there is a lot of interest to create these systems.

“This isn’t just some computer scientists coming up with their own thing, we actually had a lot of feedback and input from people in these fields,” Watts said. “They’re always looking for new technology to help improve patient outcomes, or to use for training. Most of them have been interested in this kind of technology for years and they just never had an opportunity to try it.”