Campus sexual assaults and how they are handled

Joshua Storie

Joshua StorieSexual Offences in 2015-2016

There were between 41 and 45 alleged victims of sexual offences on campus reported in 2015-16. Eight of the 12 student perpetrators were suspended or expelled.

Gender-based violence, an “ad-hoc” category in the annual Student Conduct and Accountability Report, includes stalking, intimate-partner violence, sexual harassment, drugging, and sexual assault. Deborah Eerkes, the Director of Student Conduct and Accountability, said it’s hard to interpret the reported number of offences as it only includes formal complaints to the university.

“We know these kinds of offences are severely underreported,” she said. “Do these numbers reflect what’s happening? I have no idea. And I kind of doubt it.”

While Eerkes couldn’t talk about specific cases, she explained that many behaviours fit into gender-based violence, ranging from “someone who couldn’t take no for an answer when attracted to someone else” to sexual assault with multiple complaints.

“These twelve alleged perpetrators, that’s the full range of behaviours,” she said. “It’s not that all these victims were sexually assaulted.”

In some cases, such as someone receiving unwanted texts from a student, the university could put restrictions (that don’t restrict their ability to attend classes) on the perpetrator’s movements so they can’t “run into” their victim, Eerkes said.

“You have certain privileges as a person on campus and then you have certain rights,” she explained. “It is not your right to get in the space of someone who doesn’t want you there.”

But once a student commits a sexual assault, especially with multiple victims, that student is “pretty much guaranteed suspension or expulsion,” Eerkes said.

“It’s a safety issue, and we’re balancing a whole bunch of interests,” she explained. “The person who was harmed, the person who’s accused, who by law we have to give procedural fairness to, and a whole campus of people who we need to keep safe. None of those things can be compromised.”

Complaints & Disclosures

Survivors of sexual offences on campus can take two routes of action: complaint or disclosure.

A complaint is a formal process that initiates an investigation to potentially impose charges. Complaints usually involve the Code of Student Behaviour, UAPS, Student Conduct and Accountability, and medical processes. Official complaints make up the 41 to 45 victims reported in 2015-16.

In a disclosure, the survivor tells someone such as a friend, professor, or someone at the Sexual Assault Centre, about their experience. For example, a student may disclose by asking faculty or staff to defer an exam or move to a different residence. Pearson said it’s hard to gauge how many disclosures are happening on campus.

“The amount of reports that we receive officially through UAPS or Student Conduct and Accountability probably don’t even approach the amount of disclosures and actual experiences on campus,” she said.

The university’s response to disclosures vary with the range of possible offences, according to Eerkes.

“It might be, ‘This person grabbed my breast and I want you to know but I don’t want you to expel them’ versus two people naming the same person having assaulted them,” she said.

Nuances of protecting campus

There’s a “loose team” of people who are made aware of individuals who pose threats. The team includes the Office of the Dean of Students, University of Alberta Protective Services (UAPS), the Sexual Assault Centre, and sometimes Residence Services. When someone is on their radar, an investigation is considered.

In extreme cases, the university can enact Protocol 91, a General Faculties Council policy that applies to everyone on campus. The protocol allows university officials to quickly remove a person from campus and have them subject to arrest if they come back, Eerkes said. This removes the person until a full investigation has been conducted. Unlike a suspension or expulsion, it doesn’t go on a student’s transcript.

Samantha Pearson, Director of the Sexual Assault Centre, said that if perpetrators are allowed to stay on campus, they should be receiving rehabilitation — something that’s not currently happening at the U of A.

“There’s a lot of backlash that can be received for expelling somebody,” she said. “We have a responsibility to all students on campus as well. It’s really hard to strike that balance but it’s something we strive to do.”

Repeat offences and their solutions

Pearson said 12 perpetrators with more than 40 victims last year makes sense, based on what is known about offenders on campus. Dr. David Lisak, an American clinical psychologist, found that 90 per cent of campus sexual assaults are committed by serial rapists. He also found that campus perpetrators of sexual violence averaged six victims, which backs up what the Sexual Assault Centre has seen anecdotally for a long time, Pearson said.

“We have a lot of stereotypes around what a perpetrator looks like, that sort of ‘stranger danger’ perspective on serial perpetration of sexual assault,” she explained. “But the more common profile we see on campus is somebody who’s very charismatic and has a lot of connections and social power.”

Pearson believes restorative justice could help combat repeat offences on campus. Restorative justice is not being used in sexual offences at the U of A, but is used against lesser offences, such as vandalism in Lister. Restorative justice can involve conversations with trained mediators or people who have experienced harm, Pearson said.

“The key is really creating connections and allowing (perpetrators) to recognize the ways in which their behaviours were problematic,” she explained. “Do I think that that’s going to work for absolutely everyone and is going to be a quick fix? No, it’s something we have to put a lot of hours into doing really well.”

Restorative justice hasn’t been called for in the U of A’s upcoming sexual assault policy, but it is being talked about in the policy’s committees and working groups.

“We really want to do (restorative justice) right and are putting lots of thought into how we enter into this,” Pearson said. “Most institutions haven’t engaged in those processes yet. It’s kind of blazing new ground.”

A new sexual violence policy

Gender-based violence is not an official category in the Student Conduct and Accountability report, but Eerkes has been noting each case in her database. Sexual offences fall under the official category of “Violations of Safety and Dignity,” which also includes physical offences such as fist fights.

“We have not had any way through the charges to figure out how many of these were sexual in nature,” she said. “I just started to monitor it on my own, because to me that’s an important thing to know.”

- Read the policy draft: Sexual violence policy anticipated for July 2017

Future annual reports will look different once the new Sexual Violence Policy is approved by the Board of Governors, Eerkes said. The new policy will provide better data on campus sexual offences by including more accurate categories to record them on campus, Eerkes said.

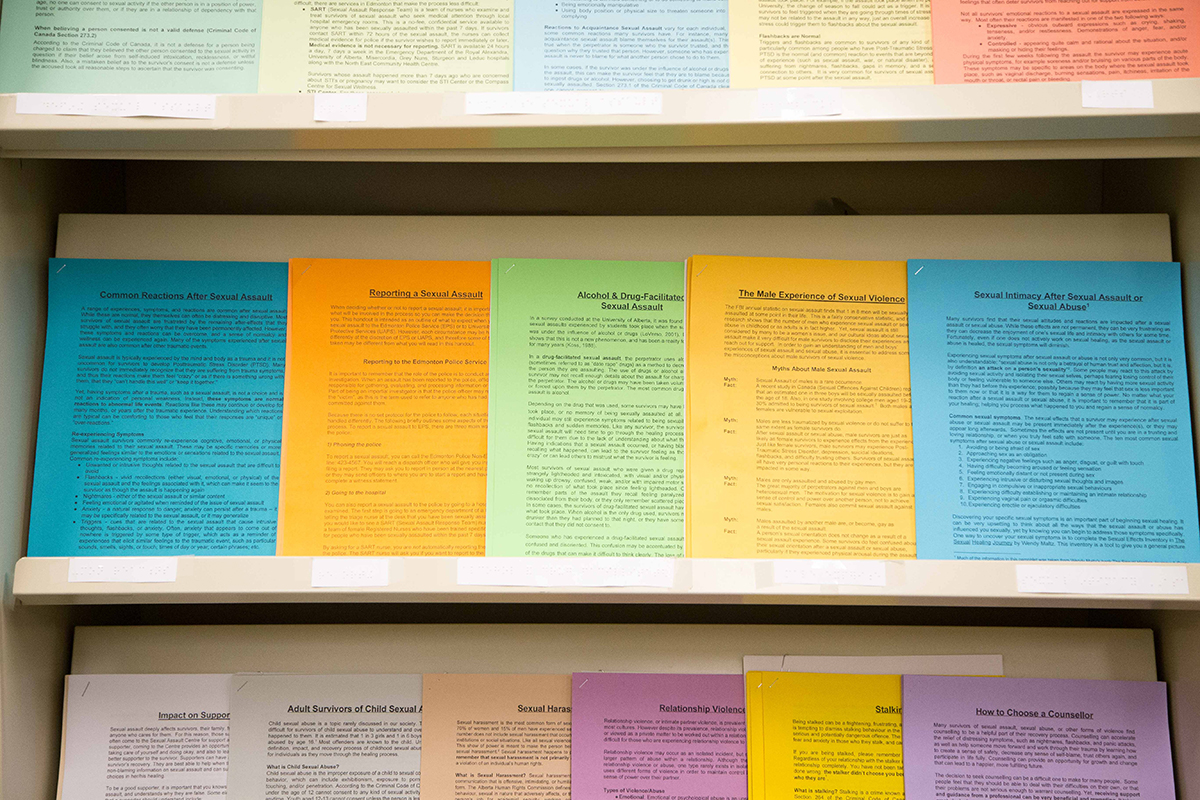

The upcoming policy also mandates training for investigators and decision-makers about how to handle disclosures. It calls for a document to communicate options for victims in one place, including counselling services and directions to resolve academic, work, or residence-related issues.

Eerkes thinks the numbers of sexual violence complaints are going to rise when the policy is finalized.

“I suspect that because all of these mechanisms will be in place and more students will know about them,” she said. “More students will disclose, and more students will make complaints.”