From street life to student life: Moving the Mountain pilot program takes young indigenous women in to an educational environment at the University of Alberta

Christina Varvis

Christina VarvisWhen Aimee Bellerose walks around the University of Alberta, she’ll overhear other’s “struggles”: a girl complaining about her hair being four inches too short, a guy talking about the party coming up on Friday, or someone else gossiping, “Oh my God, did you see her shoes?” As a 22-year-old indigenous woman who’s lived through homelessness, incarceration, addiction and mental illness, Bellerose’s concept of a struggle is much different.

The city is a different place for an indigenous person who has been in and out of the system. Bellerose, and other women in similar situations, worry about things like whether they’ll eat tomorrow or find a place to sleep tonight. Or about whether they’ll get stopped by Edmonton Police Services for jaywalking and arrested for something completely different, which Bellerose said she has seen happen.

“Go downtown, even on the south side” she said. “When you’re a native person and you walk down the street people look at you like you’re an outsider.”

Like many enrolled in university, Bellerose has gone through the provincial schooling system, and possesses a high school diploma. The challenges started early, when Bellerose could never finish mad minutes in time. She remembers being kept from recess for a whole two months as a result.

High school is harder to remember, but Bellerose’s diploma proves she got through. She was homeless during that time, and often under the influence of drugs. Those days were cold, hungry and numb, she said. What got her through was the art teacher, who’d walk Bellerose to school and make her toast and coffee every morning.

“A lot of people think (food) is a necessity. People think that only happens in Third World countries. No. In Canada, in Edmonton, food is a luxury for a lot of people. And that’s the reality,” Bellerose said.

As for clothes, Bellerose looks down at her outfit and wonders what everyone else on campus thinks of her.

Bellerose is one of the 21 young women attending the newly-piloted Moving the Mountain program, a learning initiative for high-risk youth, mainly of indigenous descent, between ages 12 and 22.

Many of the women in the program haven’t completed high school and have struggled in the education and criminal system. The majority of them are, or have been, homeless. Some have been diagnosed with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, while all have had severe problems with substance abuse.

Program facilitator Wallis Kendal said traumatized youth with neurobiological problems will cost between $2-3 million per person. Those millions flow to the system of police, group homes, disability support and social services.

The cost group home living at $15-20,000 a month and the cost of incarceration at $30,000, Kendal said. Upwards of age 20, youth are put solely on disability support. That’s $1,500 a month. Having grown up in the system, they’re directionless with money, which will likely be spent on alcohol, bad food and drugs. They become the “shadow people of the streets,” Kendal said.

Funding for preventative measures and reconstruction of traumatized lives is zero, Kendal said. That’s the mystery Moving the Mountain is trying to solve: whether these traumatized youth that have been rejected and abandoned by the system can recover their ability to learn.

In 2014, a 15-year-old girl in the Moving the Mountain program committed suicide at her group home. Right now, there’s a girl in the program who’s missing. Another girl has punched out workers in her group home. Others have been sexually exploited, or are in abusive relationships. A lot of them experience manic-depressive swings. These individuals easily fall off the radar, Department of Education Psychology neuroscientist Jaqueline Pei said.

“(The traditional system) says, ‘So why don’t you sit in a classroom and like everyone else?’ And (the youth) are like, ‘I would just like to know that I’m actually going to get food today, and maybe that I can sleep somewhere other than a street corner tonight,” Pei said. “I’m really not all that concerned on how I performed on that math test.’”

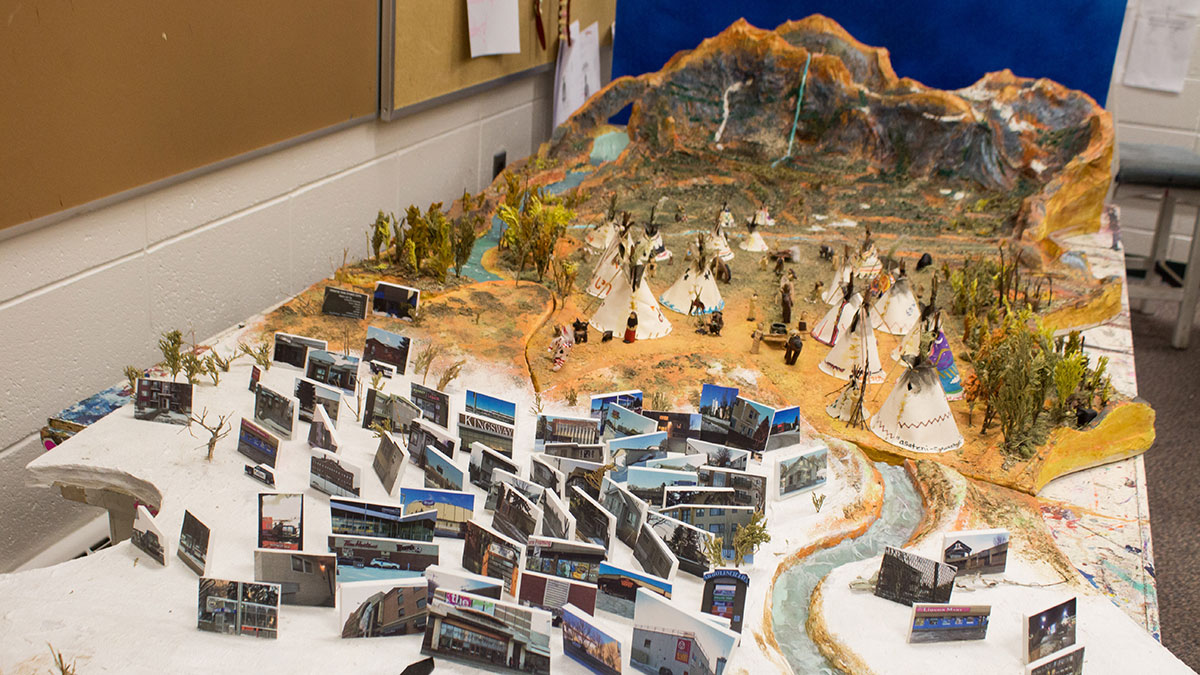

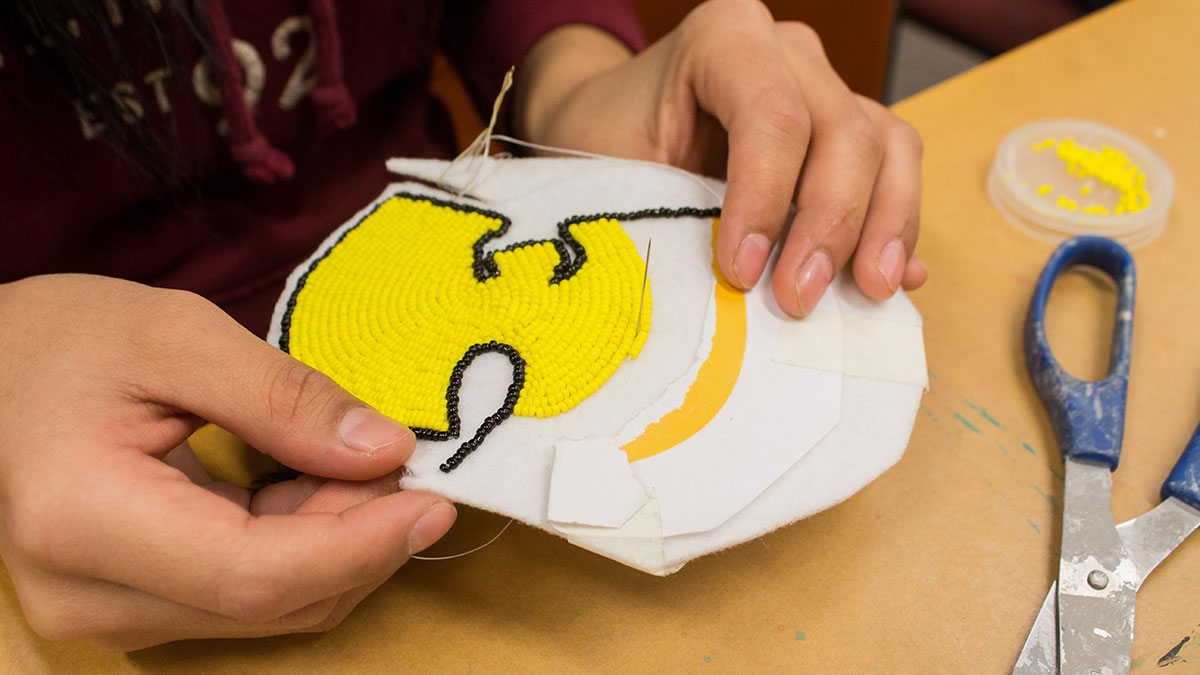

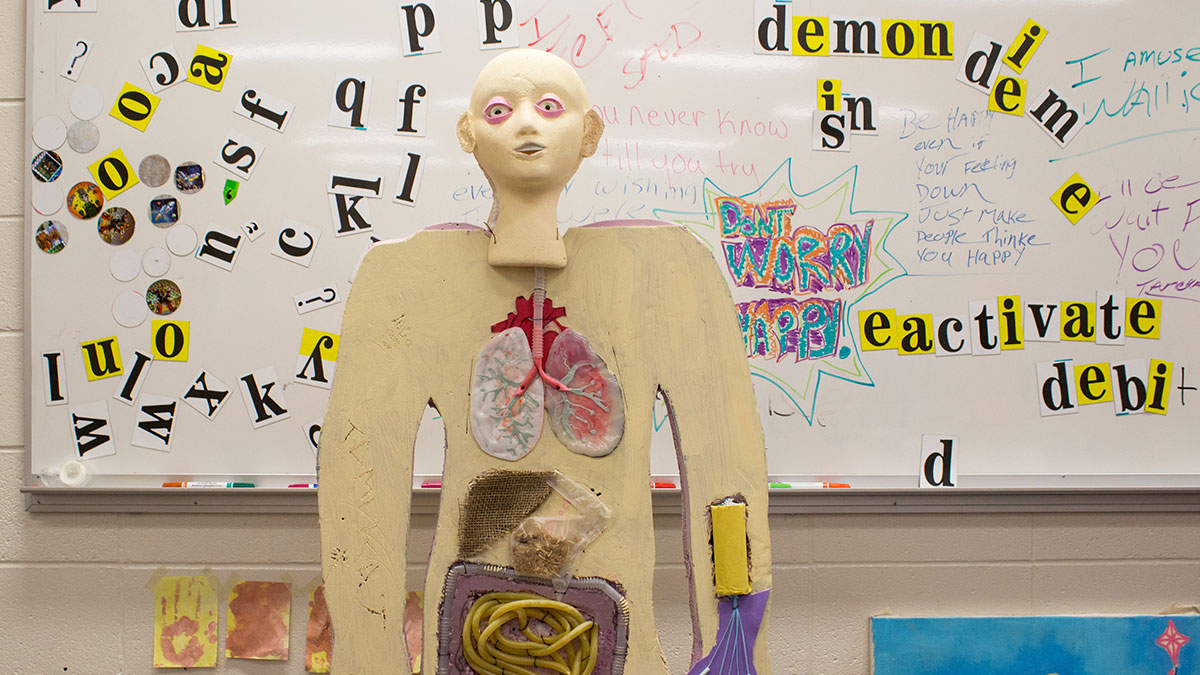

There’s no set schedules at Moving the Mountain, but youth are asked to attend three days a week. Under the guidance of Kendal and volunteers from Edmonton Public Schools, youth learn about science and history through projects and practical work. They decide to learn, which is the key point, Kendal said.

“If you can’t be independent and direct yourself to learn because you want to, you’ll never do anything,” Kendal said.

Challenges arise with the way the youth come and go. Progress harder when the youth also have to deal with group homes, bus passes, court trials, and the like, Kendal said. Funding is also troublesome. Last year, the Jaqueline Pei received a nearly $40,000 grant for Moving the Mountain from the Alberta Centre for Child, Family and Community Research. Those funds are running out though, Wallis said. Currently, the program mostly runs on donations.

For some individuals like Aimee Bellerose, the end goal with Moving the Mountain will be to attend classes and receive a formalized education. For others, it might just be learning how to manage mental illness and finding stable work.

“Sometimes little steps can take you a really really long way,” Pei said. “It just takes a while to get there.”

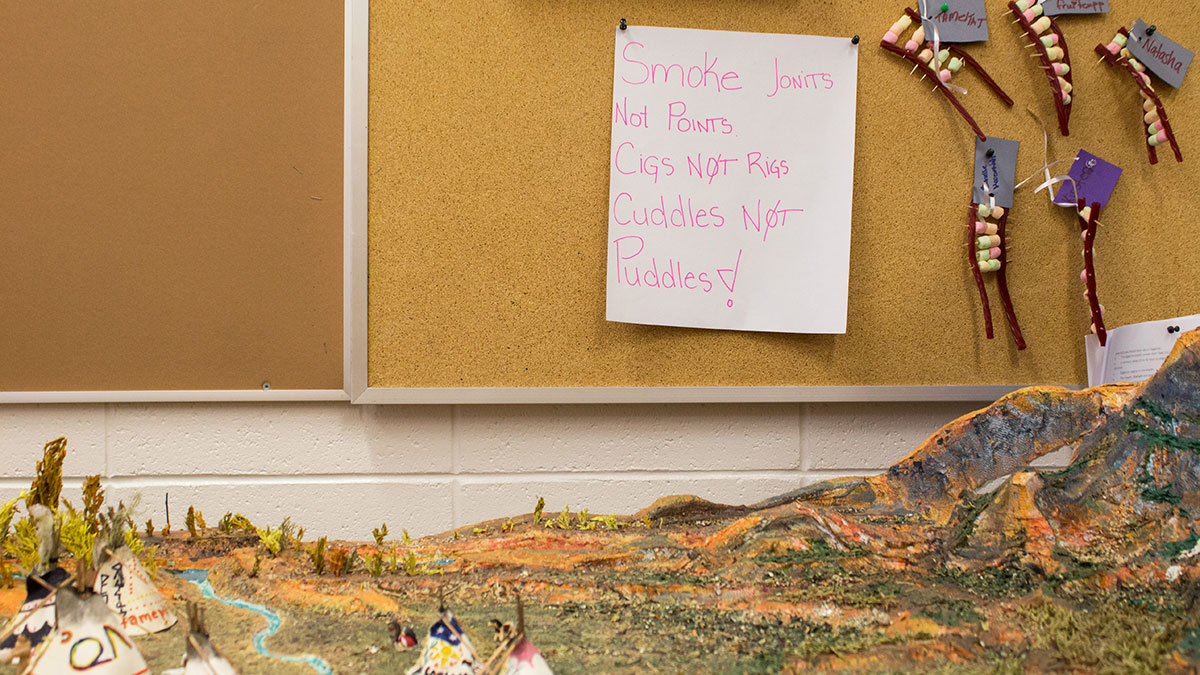

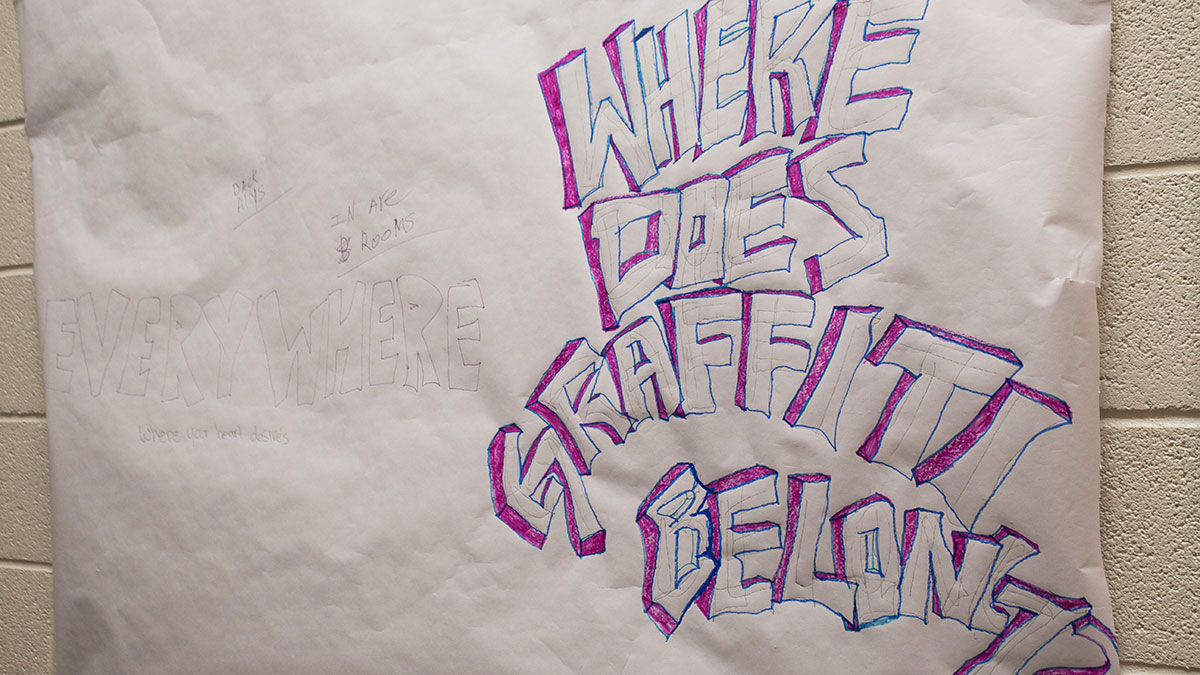

Today, Bellerose arrives at her Moving the Mountain work space at 9 a.m. There’s a decent view, she can look to the right and see whatever’s happening in the Education Gym. To the left, numerous records hang on the wall, representative of her love of hip hop music. Bellerose’s first album is set to release December, 2015 under her rap pseudonym “Persuasion.” She also knows a bit about the broadcasting aspect as well, as a volunteer at the CJSR campus radio station.

She’s also part of a Youth Action Against Poverty Team, which discusses the problems she faced growing up: homelessness, lack of opportunity, marginalization, among others.

Bellerose’s weeks are busy, they involve going to class — just to audit for now, but the goal is to enroll in classes full-time next year. Right now she’s in an early childhood development class, even though she’s not particularly fond of kids, she said. Outside of Moving the Mountain and CJSR, she feels somewhat adjacent to campus.

“Classes are weird. I’ll walk down the halls and I’ll feel really ghetto. Everyone stares at me like I shouldn’t bring a backpack or something. I feel judged sometimes here,” she said.

Like most people on campus, Bellerose will tell you she’s not sure what she wants to study. But she’s okay with it, in indigenous culture life is believed to happen in cycles, and she’s comfortable with following many different paths.

“We’re not meant to decide what we want to do forever,” she said.

Bellerose calls herself “blessed with opportunity.” She’s free to create art, free to engage in campus community, and free to simply go for a smoke when she wants — which is nice for when class gets stressful.

Next year, Bellerose is probably going to be taking courses in art therapy and psychology. She loves the former, and is fascinated by the latter.

“I’m scared. But I know that I’m smart, and I know that I can handle it,” Bellerose said.