Renowned journalist got head start at The Gateway

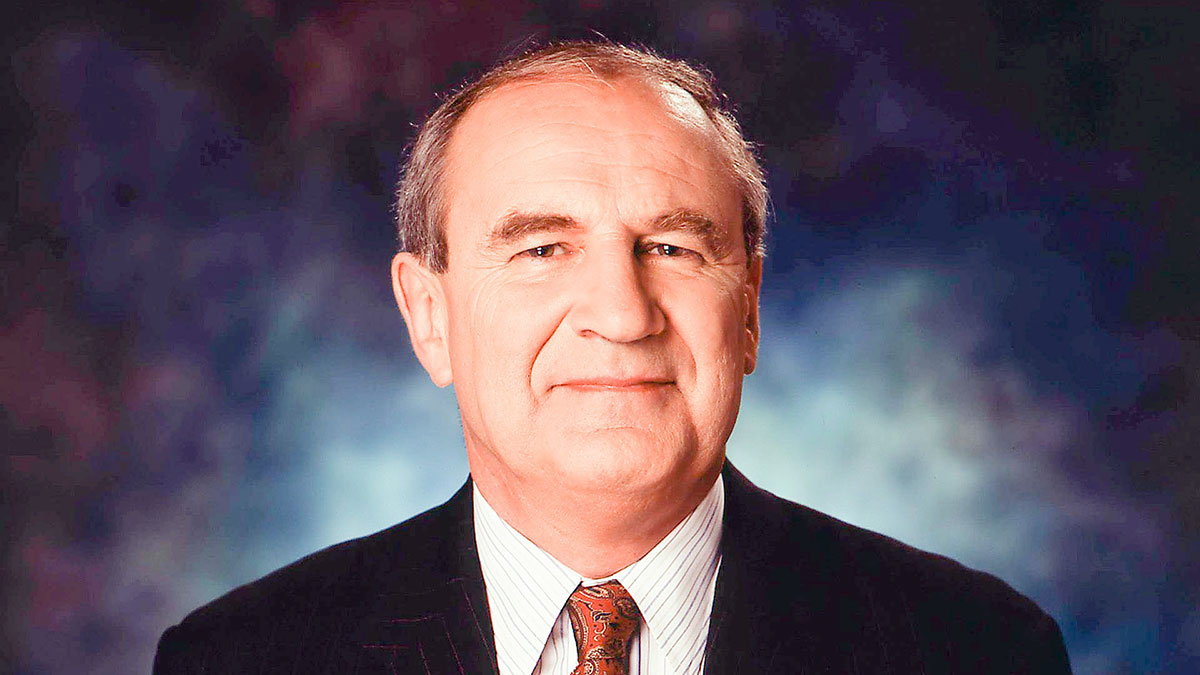

Supplied - CBC

Supplied - CBCIn 1927, Matthew Halton was a third-year student at the University of Alberta with great aspirations to climb the ladder in the world of journalism. But what he didn’t know then was how fast or how far these aspirations would take him.

His career began with a rapid transformation from a reporter at the U of A’s student newspaper, The Gateway, to a European correspondent for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), reporting stories from the front lines of the Second World War.

His son, David Halton, also an acclaimed former CBC correspondent, examines his father’s successful career in journalism in his latest book, Dispatches from the Front: Matthew Halton, Canada’s Voice at War.

“Alberta was a very important part of my dad’s growing up, and his formative influences at the U of A,” Halton said.

In the biography, Halton explains how his father came from a poor English immigrant family settled in Pincher Creek in the early 1900s. As a U of A student, his talent for writing was recognized “very quickly” as he became the Editor-in-Chief of The Gateway in his third and fourth school year, Halton said.

“He wrote very well, in an elegant way,” he said.

In Matthew’s time at The Gateway, he wrote a controversial editorial criticizing organized religion. Halton said that his father’s writing on the subject resulted in some of the religious students on campus pushing towards cutting off funding for The Gateway, an attempt that ultimately failed.

Matthew also quickly expanded his credentials as a journalist by reporting for both the Edmonton Journal and the Edmonton Bulletin — which published between 1880 and 1951.

A year after he joined the Toronto Star, the Alberta-born journalist went to Berlin as a CBC correspondent to write about Adolf Hitler’s seizure of power — and was one of the first correspondents to sound the alarm about Hitler in 1933.

But at the time he was accused of being a fear monger and sensationalist in Canada, something Halton uncovered in researching his father’s past.

“There were surprises when I wrote about (his career),” Halton said. “It’s remarkable to think of what people actually thought of Hitler at the time.”

Matthew’s career soon saw him speaking with an exiled Haile Selassie and Leon Trotsky, being brushed off by Lawrence of Arabia, receiving warnings of degrading violence from Gandhi, and getting scolded by Babe Ruth about cricket.

But his success took a toll on him as concerns that he was suffering dementia were looming when he died of an apparent stroke in 1956 at age 52, following a stomach surgery to remove ulcers.

Halton said he vividly remembers his father as supportive and caring.

“He was a good father,” he said. “He would always help me with homework and take me out to expensive restaurants if I did well at school.”

Halton, who was only 16 years old when his father died, said he never had much of a chance to talk to him about his career — which led to several interesting realizations when he was writing the book.

He started writing Dispatches from the Front when he discovered that his father’s name was largely forgotten to most Canadians upon returning to Canada after 14 years of being a correspondent for CBC in Washington.

“(I wanted) to reawaken people’s interests in a guy who has been often described by historians as Canada’s greatest foreign war correspondent,” Halton said. “Dad was quite brave.”

— with files from Andrea Ross