Former Supreme Court Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin reflects on law career

In her talk at the U of A, McLachlin talked about her initial decision to go to law school in the 1960s

Adam Lachacz

Adam LachaczFormer Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada Beverley McLachlin spoke at the University of Alberta about how she first decided to enter the profession of law.

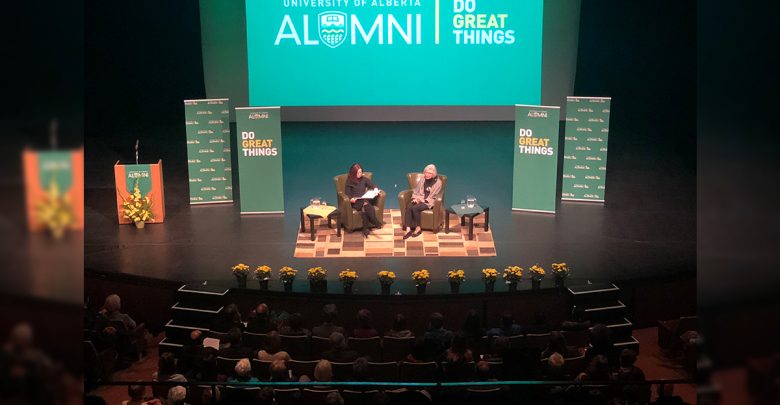

As part of U of A Alumni Weekend, an annual event allowing alumni to reconnect, McLachlin spoke at the Myer Horowitz Theatre on September 22. She recounted her time on the court, the highlights of her career, and how she got into law. McLachlin also listed some hopes she has for the future of the justice system.

McLachlin is the longest-serving chief justice and the first female to serve in that role. She oversaw several significant rulings in her career, including striking down anti-prostitution laws, and legalizing gay marriage and doctor-assisted death.

McLachlin earned four degrees from the U of A, including a bachelor of arts, master of arts in philosophy, a bachelor of laws, and an honorary doctorate.

In her talk, McLachlin said it “never occurred” to her consider law as a profession while attending university in the 1960s.

“The only lawyers I ever knew were men,” she said. “And I didn’t know too many of them.”

She said she wrote a letter over the summer to the dean of the faculty of law asking for information about law to help her decide whether to attend.

“He wrote back by return mail, ‘You’re admitted,’” McLachlin said.

She gave law a chance and “loved it from day one.” McLachlin said since then, she’s never left the profession.

“I felt at home,” McLachlin said. “I enjoyed… getting to the bottom of something and picking a complicated situation apart.”

McLachlin said a highlight of her career included overseeing the implementation of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms into the Constitution of Canada. According to her, in 1982 no other country had a comparable document and it created a new precedent for law in Canada.

“The development of the equality right and the rights and freedoms under the Charter was an enormous jurisprudential venture because there was no blueprint for it,” she said. “It was up to the courts to fill in the blanks and interpret all these new rights.”

One area of law McLachlin said she was most passionate about was Indigenous rights.

“You could hardly talk about Indigenous rights when I [first] became a judge,” McLachlin said. “They were just starting to emerge… Now, we have an impressive body of jurisprudence setting out Indigenous rights.”

She added that all Canadians, not just lawyers or judges, should seek out the Indigenous perspective to learn from their culture and knowledge systems.

“I think our goal should be to ensure that the legal system is seen by Indigenous people as theirs,” McLachlin said. “It is not an alien or colonial system imposed on them, it is a system in which they are welcome and fairly treated.”

McLachlin said society has outpaced the current legal system and that the Canadian system is plagued by long wait times. She added that future governments should work to ensure that there are no wait times for court proceedings and that everyone can access justice since the courts are the most important apparatus of the state.

“If a citizen comes before you… [judges] should not and cannot say go away, we do not want to hear your case,” McLachlin said. “We have to take the case, we have to listen, and give the best possible decision that we can. That is what I have always tried to do.”