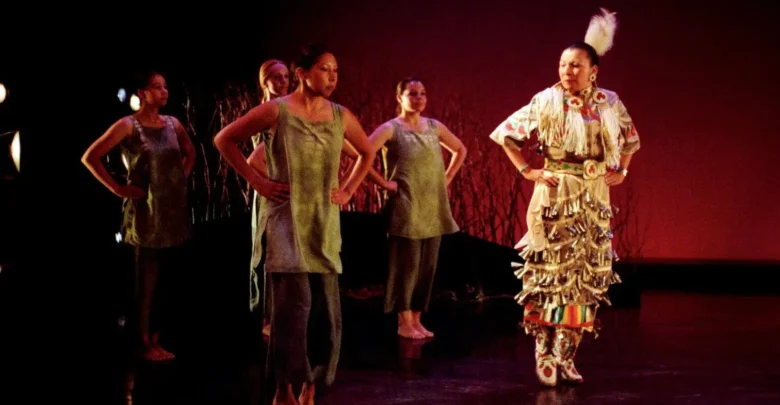

Karen Pheasant-Neganigwane’s grounding life of dance

Pheasant-Neganigwane was recently inducted into the 2023 Dance Collection Danse Hall of Fame. For her, this award is an affirmation of powwow as a dance form.

Supplied

SuppliedA lecture hall of 400 students answered Kahoot questions to review for their final exam. Over the course of 12 weeks, the students were taught about Indigenous history and of Canada’s historic treatment toward Indigenous peoples. One question asked students, “why do average young [Indigenous] people not succeed?” Responses included answers along the lines of, “they’re lazy, drunk alcoholics.”

Karen Pheasant-Neganigwane looked into the lecture hall after seeing these responses. As part of the class panel discussion, it was her turn to present.

“The air was so awkwardly silent,” she recalled. “I said, ‘how do you think I feel? How do you think I feel, or my children or my grandchildren, knowing that Canadian society thinks that of us?'”

Pheasant-Neganigwane was wearing a ribbon skirt that day. She didn’t know what to do, but she managed to “find song within herself.”

“I danced — I do a jingle dress side-step song, which is a healing song. I proceeded to dance in silence, but I could hear a song. [I danced] just enough to regain myself, to recompose myself, to capture my spirit in a good way,” she explained. After she finished, she told the class, “that’s what I do.”

“That’s what I do knowing what Canadian society thinks of us. I dance with my children [and] grandchildren, to remind myself of how amazing, brilliant, and courageous we are.”

Pheasant-Neganigwane is an Anishinaabe of the Three Fires Confederacy. She is also a scholar, writer, orator, and life-long powwow dancer. On November 5, she was inducted into the fifth-annual 2023 Dance Collection Danse Hall of Fame.

“My life of dance was a grounding force and a way of protection,” Pheasant-Neganigwane says

Pheasant-Neganigwane’s parents attended residential school. “They vowed that their children would not go through what they went though,” she said. So, as a child, Pheasant-Neganigwane attended public school in the city. But, every free moment was spent at home in Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory on Manitoulin Island, Ontario.

Pheasant-Neganigwane watched powwows all the time growing up, especially at Wikkwemkoong’s powwow celebrations.

“My mom has a story where I pleaded [her] to make me a powwow dress so I can go and dance,” she recalled.

“When I went onto the dance floor and the drums were going, I can say now as a scholar, the reverberations of the song and drum touched my soul. But when I’m a little girl, all I know is the bliss that I felt. My dance is always about finding that bliss.”

In 1981, Pheasant-Neganigwane left her home in Toronto to pursue dance. She later moved to Alberta in 1984. When she came to Edmonton, it was hard because all she had was her powwow community.

“It was my grounding force. I plugged along, raising my children. I raised my children as dancers, and now they raise their children as dancers,” Pheasant-Neganigwane said. “Dance isn’t like an art form for us. True, it’s an expression. But my life of dance was a grounding force and a way of protection.”

Pheasant-Neganigwane’s pursuit of academia

Aside from dance, Pheasant-Neganigwane knew that she wanted to pursue academia. Currently, she is an assistant professor at Mount Royal University, and a University of Alberta PhD candidate on the topic of Anishinaabe and Indigenous pedagogy. She received a Master’s of Education Policy Studies at the U of A in 2013.

As a teenager, she spent time at the University of Toronto. It was there her interest in academia developed.

“[There were] people around us all the time, prodding and researching us. And I was just always intrigued,” Pheasant-Neganigwane recalled.

During her first undergraduate year at the University of Lethbridge, her professors included Leroy Little Bear and Thomas King. This sparked her dream to become a scholar.

“I thought, wow! We have Indians here being professors. It set the dream. I just thought, I want to be here.”

Pheasant-Neganigwane’s journey in academia was not easy. At one point she stopped dancing and teaching dance workshops at the Canadian Native Friendship Centre.

“When I started grad studies in 2012, it was so overwhelming. So, I put my dance aside,” Pheasant-Neganigwane recalled.

But, at a job interview in 2019, she was asked about a teaching challenge she’s encountered. She told the story of facing a 400-student lecture hall and dancing.

“My dance is what saved me,” she said. “When I dance, it’s just a moment of beauty. It’s a moment of bliss. I get to be myself.” Now, Pheasant-Neganigwane starts all her classes with music on the first day.

Being inducted into the 2023 Dance Collection Danse Hall of Fame is “an affirmation of our dance”

Pheasant-Neganigwane is in the final stages of writing her dissertation. Coupled with being inducted into the 2023 Dance Collection Danse Hall of Fame, she “sees the light at the end of the tunnel.” She added the award is “an affirmation of our dance.”

“I do my dance to heal me. To save me. To ground me. And I raised my children that way because it’s something we did as a family,” Pheasant-Neganigwane explained. “In my three-minute acceptance speech, I acknowledge I’m just in amazement that they acknowledge the powwow dance as a form.”

“I’m really grateful that my mom and dad listened to that little girl. As a teenager, they took me. They didn’t know anything about powwow. They just knew that that’s where I wanted to be.”