‘Three words for three years:’ How has COVID-19 affected the U of A community?

"It's clear that a lot of people had things in their head about the pandemic that they wanted to note, and interact with others about as well," U of A assistant professor and Kule Scholar says.

Lily Polenchuk

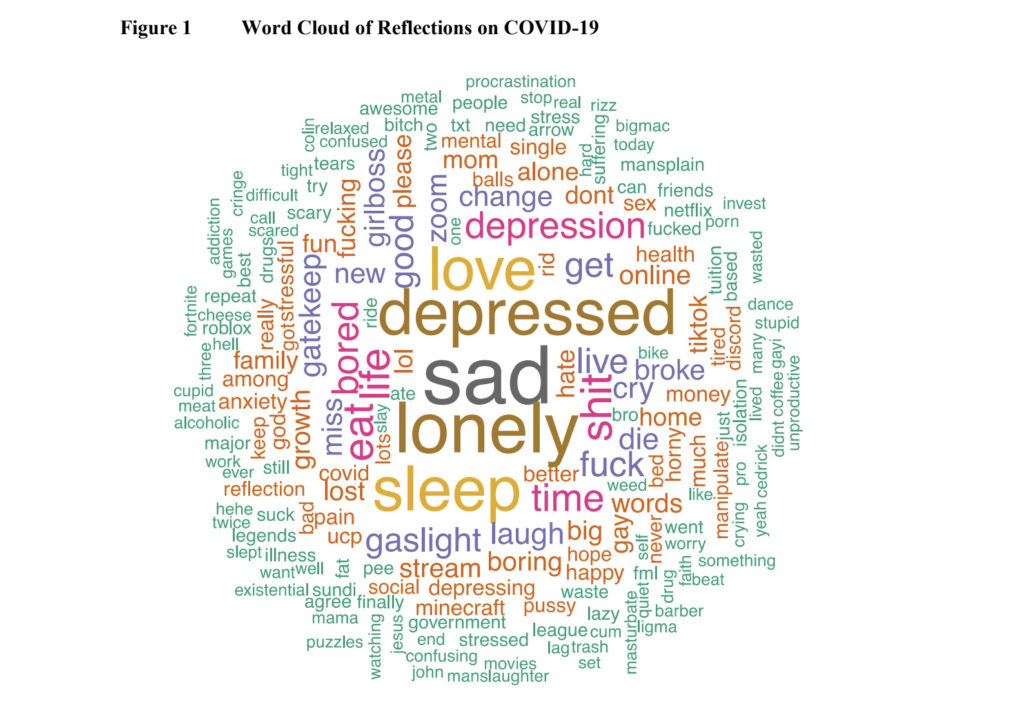

Lily Polenchuk“Sad,” “lonely,” “sleep,” “depressed,” and “love” were the five most common responses from the University of Alberta community when given the following prompt: “Three words for three years: The COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020. What three words describe your life during COVID-19?”

The 2022-25 Kule Scholars Cohort posed the prompt to the U of A community on whiteboards set-up at five U of A libraries in the last two weeks of March 2023. The results found that “many individuals in the U of A community faced a profound life experience over the pandemic.”

The cohort is a group of researchers from different disciplines whose work focuses on the theme “Politics, Pandemics, and Misinformation.” Michelle Maroto, an associate professor in the department of sociology at the U of A, is a member of the cohort.

“Our goal is to put together a lot of different projects around these issues over the next couple of years,” Maroto said.

“We decided to give people a place to think about the pandemic, about how their lives have changed,” Maroto says

Maroto explained that the prompt aimed to get people to reflect on the past three years. The use of whiteboards gave people the chance to read and interact with other responses.

“I think we all know our lives have changed a lot since March 2020. There have been ups and downs, and we’ve all ended up at different places,” Maroto said.

“So we decided to give people a place to think about the pandemic, about how their lives have changed, and to try and describe that in a very short form.”

Across the five libraries — Augustana Campus Library, Cameron Library, the John A. Weir Memorial Law Library, Rutherford Library, and the John W. Scott Health Sciences Library — there were 1,080 valid responses. After taking out whitespace, punctuation, and unclear phrases, the scholars created a word cloud of 1,333 separate words.

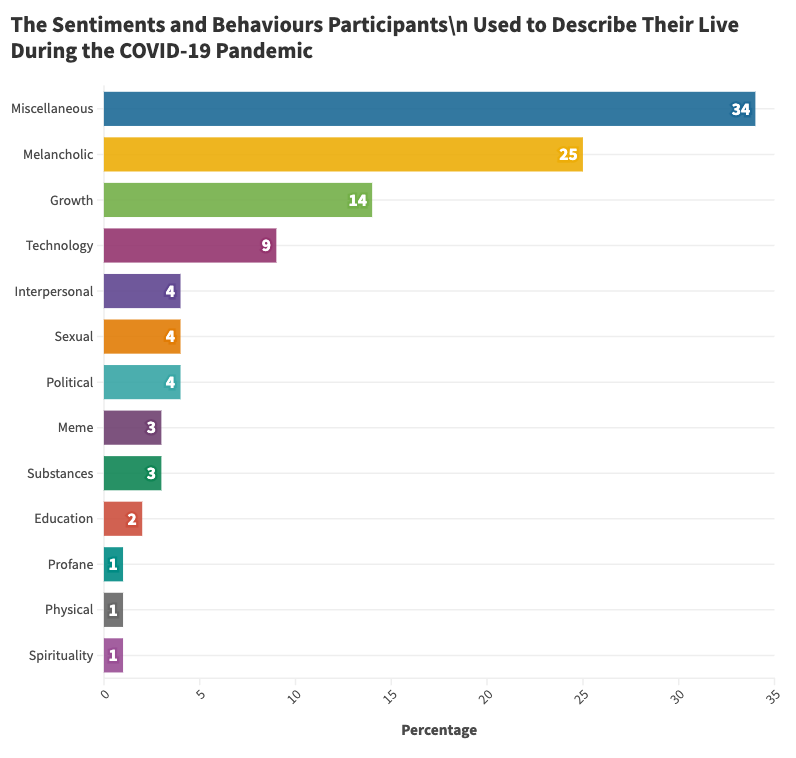

From the sentiments and behaviours that came out of the responses, the scholars made 13 categories. The most common category was miscellaneous, with 34 per cent of responses. Responses under this category lacked a clear connection to the prompt or a consistent theme.

The second most common response category was melancholic, with 25 per cent of responses. This category’s responses “illustrated a moody, dull, uncertain, or disruptive experience during the pandemic,” according to the results summary. Out of the 1,333 words, the most common words were “sad,” “depressed,” and “lonely.”

Maroto said that the pandemic came with people getting sick, loss of loved ones, isolation, financial struggles, and unpredictability.

“We get the sentiment that there is this sadness that was going through people’s minds when they were thinking about how life was over the past three years throughout the pandemic,” Maroto said.

“It seems like in a lot of ways with COVID-19, we just want to be done with it and not talk about it anymore,” Maroto says

The third most common response category was growth, with 14 per cent of responses. Responses under this category described the pandemic as a positive, reflective, and developmental experience. Maroto said that this could be due to the extra time people had during isolation.

“I think that’s partly because the pandemic gave people time to focus on themselves in different ways, and maybe do things that they wouldn’t have necessarily been able to beforehand,” she said.

“There’s a balance — people were sad, lonely, and depressed. But I think a lot of people also tried to use that time in different ways.”

According to the results summary, the number of responses in the melancholic and growth categories shows that “many individuals in the U of A community faced a profound life experience over the pandemic.”

For Maroto, the results show how the pandemic affected people in many different ways. She added that COVID-19 is something people do not seem to talk about.

“I don’t think we’ve necessarily had enough time to sit and reflect upon it. For other big crises over time, there’s been more opportunities to reflect and talk about it. It seems like in a lot of ways with COVID-19, we just want to be done with it and not talk about it anymore,” Maroto said.

“Which is partially why we wanted to give this opportunity for reflection. It’s clear that a lot of people had things in their head about the pandemic that they wanted to note, and to interact with others about.”