Melanin mental health: A Black student’s pursuit of culturally responsive therapy

Stigma surrounding therapy that Black students face adversely affects their ability to seek mental health support.

Richard Bagan

Richard BaganThis guest column is written through a partnership with the University of Alberta Black Students’ Association and The Gateway.

Trigger Warning: This article discusses topics related to sexual assault and violence that some readers may find upsetting. Resources are available at the end of the article.

In the pursuit of a healthy mind, students of colour anticipate cultural insensitivity from mental health professionals. Disappointing experiences with psychologists validate the fear that our experiences will not be handled with care and attention. Unfortunately, it dissuades us from seeking help in the future.

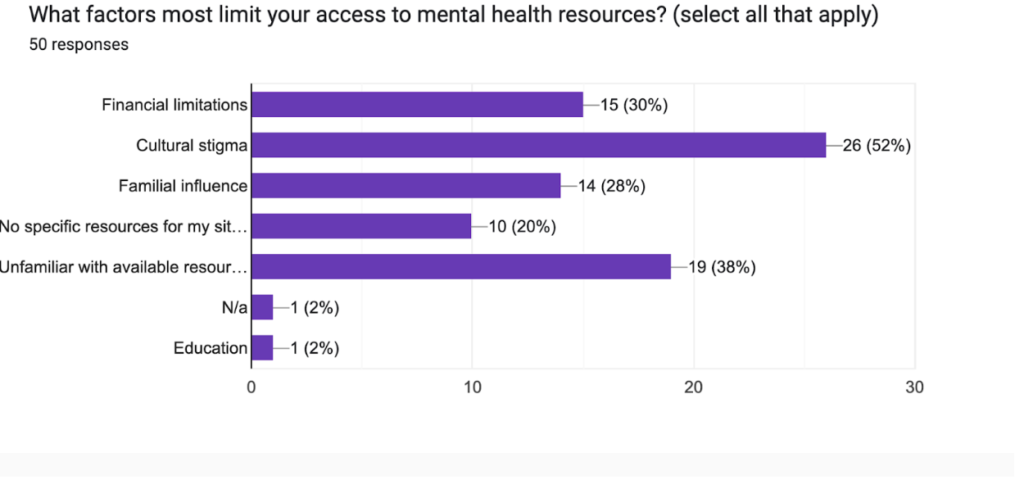

The University of Alberta Black Students’ Association (UABSA) conducted a survey in 2020. It identified stigma as the leading barrier to accessing mental health services on campus.

Studies show that stigma fosters fear that culturally-insensitive counselors will misunderstand or minimize problems, worry that disclosing negative information in counseling sessions could contribute to the cultural stereotyping of the students’ racial group, and concerns that treatment will be ineffective or even oppressive. In order to understand the stigma, and consequent mistrust in mental health services, we consulted Suman Varghese, a registered psychologist at the University of Alberta’s Counseling and Clinical Services (CCS).

In our interview, we asked if psychologists and counselors at CCS receive training in cultural and racial diversity.

Varghese noted that in postgraduate school, cross-cultural training is now part of the coursework. As a staff member in the clinic, she has been a part of training sessions. They cover a range of marginalized communities, with one of them being a historical trauma workshop specific to Indigenous students. Learning how to handle the life experiences of marginalized communities is emerging as a mainstream priority.

“The profession as a whole is coming to a reckoning,” Varghese said.

A tide is turning, albeit slowly. These workshops are raising the standard for mental health care providers — offering cultural sensitivity is becoming more common, and thus is becoming more expected from clients.

“Training and awareness has always been lagging, but we are at a turning point now where it’s starting to shift.”

Black students can request psychologists who are Black, Indigenous, and people of colour (BIPOC) to ensure their care is managed by someone who understands the nuances of a marginalized person’s struggles.

Unfortunately, the demand CCS experiences for their services means that Black students’ requests for therapists of colour cannot always be met, increasing their chances of encountering culturally unresponsive therapy. We settle for the available, and in the process risk sacrificing the ability to relate to our mental health care provider.

Outside of the CCS, my own experiences with culturally unresponsive therapy have been shallow and littered with omission. The racial elements to my life were not deemed worthy of exploration, so I chose to not include them entirely. When your life is intertwined with your race and ethnicity from day one, a mental health professional not prioritizing the issues of racism and microaggression seems absurd.

If our life experiences are shaped by our race and ethnicities, how can we expect therapy to be effective if these factors are ignored? Encouraging people of colour to seek therapy without discernment is reckless. It very well might cost them their time and money with little to show.

In response to this deficit, the BIPOC community is calling for culturally-responsive therapists to serve our community. Culture is the diverse expression of our shared humanity. It is the sense of belonging within a group of people, and it shapes perspectives and feelings. Both of these have a direct impact on relationships with others and oneself.

Often, therapy conversations may start with culture, but end up being about race. Appreciating the intersection between the two is critical. It is equally important, however, to recognize culture as being separate from race. Race focuses on skin-deep issues that divide, while culture allows for the appreciation of the human experience as the accumulation of customs, beliefs, and values. Someone cannot change their race, but the effort to learn about race relations and its effects on mental health is a cultural responsibility for providers who plan to serve minorities.

That being said, it would be refreshing to see mental health care providers who are knowledgeable, and willing to learn, about the cultural nuances of their clients. Incorporating such training is the first step in deracializing the broader field of psychology, and lessening the fear Black students carry in their search for mental health care.

The Black Students’ Association recognizes Counseling and Clinical Services’ (CCS) efforts to provide support that is receptive to the cultural and racial experiences and concerns of students and we encourage students to seek out mental health resources available for students.

The CCS offers free psychological treatment services to students. In order to assist students in successfully navigating their university experience, CCS uses a short-term behavior model focused on their current level of mental health or illness. To see a counselor on campus, a student must first complete an Initial Consultation (IC). Book an IC by calling CCS reception at 780-492-5205 on weekdays, between the hours of 8:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m..