Community and connection: What is the future of safety and security on campus?

Jin He

Jin HeCampus safety has been an ongoing issue for several years, but the conversation climaxed at the end of the Winter semester this year with a combative council session that revived stories of student assault, raised questions about a mid-exam season consultation process that left some feeling unheard, and the colonial practices of the police, the university, and students themselves.

Final council meeting stretches six hours: a tension-filled ending to council’s term

During the April 19 Students’ Council meeting, council discussed their Campus Safety and Security Policy.

This policy outlines the University of Alberta Students’ Union’s (UASU) advocacy for the municipal and provincial governments to invest in harm reduction security services and strategies to be used off-campus. The policy also prioritizes inclusivity for Black, First Nations, Métis, and Inuit (FNMI), 2SLGBTQ+, and disabled leaders on the U of A’s campus while undergoing a review of safety and security practices on campus, including University of Alberta Protective Services (UAPS).

This policy is heavily guided by the results of the Campus Safety and Security Survey done in August of 2021. One-fifth of the facts provided in the preamble come from that particular survey. Based on the feedback of that survey and movements such as the Black Lives Matter movement, the policy says that “while security and policing personnel make some feel safe, security and policing present both a real and a perceived threat for many marginalized groups.”

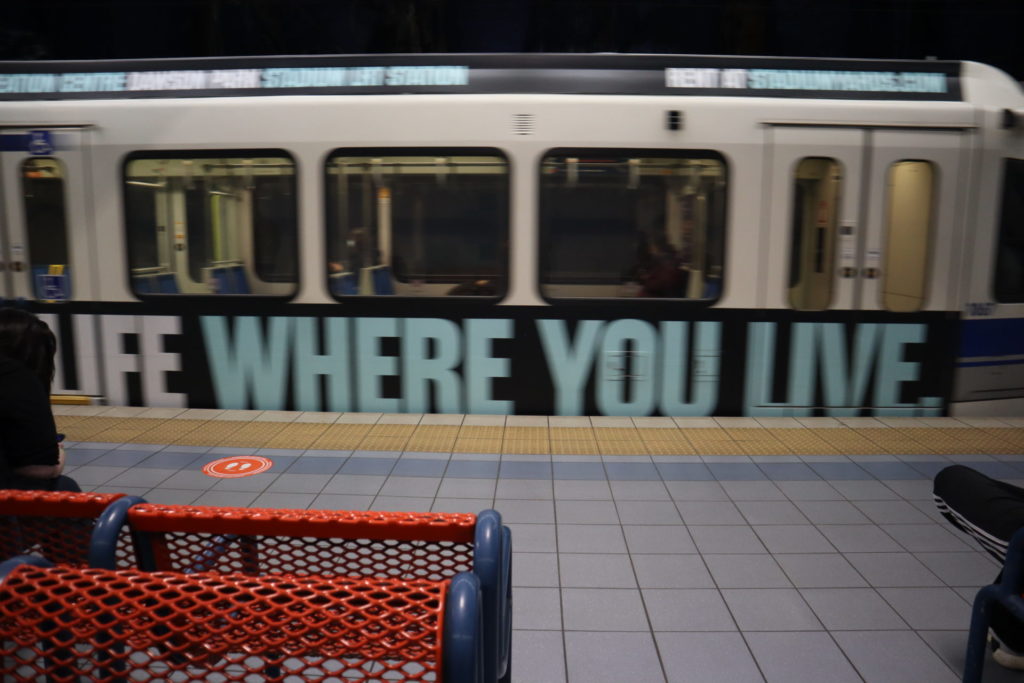

In opposition to the policy, the International Students’ Association (ISA) gave a presentation, which voiced concerns that safety measures in the policy were not properly considered for international students. Notably, the presentation gave various examples of international students who had experienced violence on transit near the university campus.

The ISA’s presentation also highlighted a survey they conducted, in which 88 per cent of 248 respondents expressed they “feel comfortable with the presence of Edmonton police on campus.”

To address their concerns, the ISA proposed to either table the policy until one more consultation session was done, or take out Second Principle 13, and pass it that night. The ISA proposed that if the latter was not possible, then a compromise should be reached where the UASU does not advocate for peace officers to be removed from transit stations.

Second Principle 13 of the policy states that “the UASU will advocate to the municipal government for improved safety on transit. This advocacy should focus on harm reduction and community-based strategies to improve safety in transit.”

Following all presentations, open forum gave guests the opportunity to speak. Representatives from the Indigenous Students’ Union (ISU) recalled their own experiences with policing and the use of policing as a colonial tool.

Shannon Cornelsen, vice-president (consultation and engagement) of the ISU, said that the policy’s mandates “reflect [their] own safeguards that [they] feel are necessary on [their] own traditional lands.”

Non-councillors who were executives of the ISA gave statements about their experiences on transit and opposed the policy — in particular, Second Principle 13. Other international students were also present at the meeting to oppose the policy.

Prior to voting on the policy, claims about length of consultation cropped up. The UASU asserted that the policy had been in the consultation process for over one year, while the ISA claimed that they had seen the policy for the first time on April 6 — just under two weeks ahead of that night’s council meeting.

So they had this timeline. They were rushing on it, but I think they should have consulted well in advance — not in the last week.

Dhir bid, ISA president

When it came time to vote on the policy, a motion to vote by roll call in lieu of a secret ballot vote was suggested by Chanpreet Singh, former ISA president. “This decision needs to be transparent, and the students who voted for you all need to [know] what you decided … council should vote for their constituents.”

The motion was struck down by the speaker in the interest of time. The Campus Safety and Security Policy was passed with 94 per cent votes in favour, after which the ISA called all attending on their behalf to participate in a virtual walkout.

UASU says proper procedure was followed for “modest proposal”

Christian Fotang, vice-president (external) of the UASU, was present when the policy was presented to council. He noted that the policy is purposefully vague, leaving room for further interpretation and nuance.

“[The] policy offered a very modest proposal,” Fotang said. “So really, our stance right now is just to review the current processes of security on campus and address the different student needs.”

Specifically, issues that were mentioned included advocating against a UAPS plainclothes unit and shifting wellness checks in residence from UAPS officers to social workers and mental health workers.

Concerning the claim that the policy did not receive adequate consultation with the ISA, Fotang said that he believes the committee that put the policy together “did [their] due diligence.”

“We had various meetings with different groups,” he said. “We ran the polling. We did everything we needed to do to pass the first principles, worked some more, and then we’d gotten all the feedback we needed.”

“All the proper processes were followed.”

Fotang also urged students to read through the entire policy. He states that the policy “does not call for the removal of UAPS on campus,” or necessarily a reduction of their responsibilities and power.

“[The policy’s preamble] mentioned abolition, but that is not reflected in the resolution.”

In Second Principles eight through 11, the policy advocates for the university to invite marginalized communities “to determine what should be changed, abolished, or improved on campus to make U of A a safe(er) and secure place.”

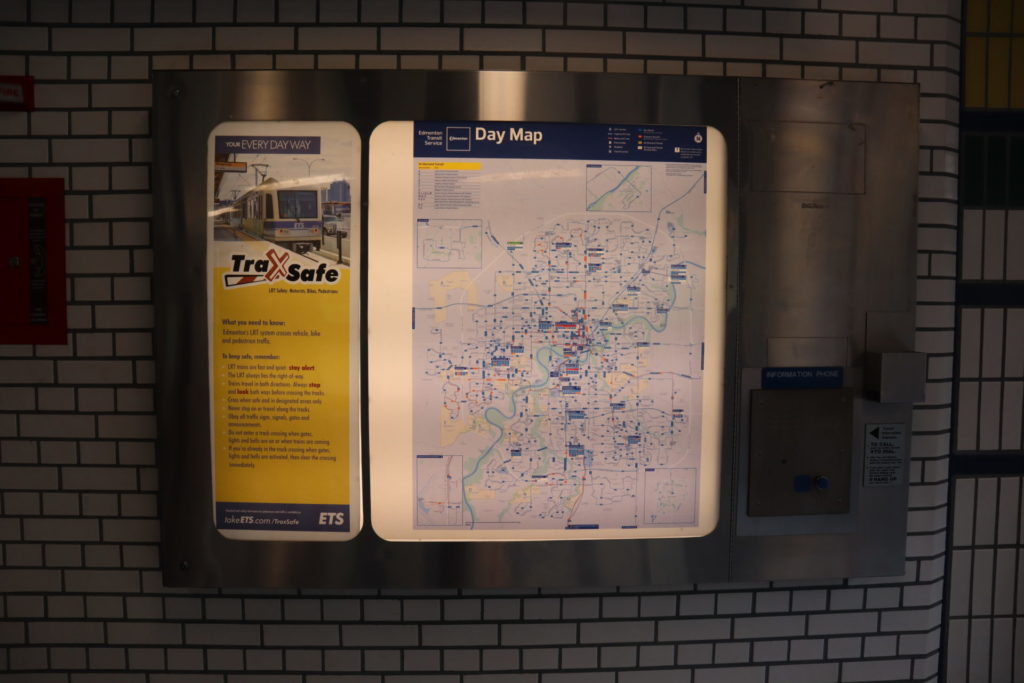

In the short-term, the policy hopes to address student concerns about transit safety and increasing UAPS transparency such as: funding information to be made publicly available, tracking average response times, and tracking and reporting their ticketing.

International Students’ Association concerned about contradiction in policy

While Dhir Bid, the president of the ISA, was not yet the head of his organization, he was at that council meeting. He explained that for international students, this policy came at a time when safety is on their minds.

“I think international students are finding it unsafe to use transit and that’s the only option they have,” said Bid, explaining that most international students do not have a car. “This may affect international student enrolment, and may make international students hesitate to use transit.”

The policy came at the end of the year, the last council meeting of the term, with consultation during exams season. Bid said this is also right before the Students’ Union executive turns over.

“They wanted to make sure that this policy is passed … before they leave, because they didn’t want it to be lying around and no one takes action on it the next year,” he said.

“So they had this timeline. They were rushing on it, but I think they should have consulted well in advance — not in the last week.”

Bid explained that for international students who have to take a full time course load, this was an extremely busy time for advocacy and consultation. That said, there was one key change made during consultation in light of concerns raised by international students.

“Initially, they were planning to advocate against UAPS and … we were trying to push for more security on campus,” he said. “So then they removed [the clause which said they would] advocate against UAPS … to keep it more general.”

However, there were concerns that the wording of the policy made it clear that it was originally advocating for decreased police presence on campus, despite being general.

“If you look at the pre-ambulatory clauses, it’s all talking about the wrong things that protective services have been doing to minority groups and underrepresented groups — which I think is right,” Bid said.

However, this didn’t line up with what the ISA was being told the policy was about.

“Their policy doesn’t want to advocate for more transit officers, more peace officers, more security, but they’re telling the ISA that you can do all this — in contrast to our policy.”

The end result was the ISA left feeling like international students were inadequately consulted and their voices were not being heard. That was the lead up to the ISA organizing a protest for that council meeting.

“The ISA has never been against community-based strategies and harm reduction strategies, we think it’s a great idea,” he said. “But this is a long-term solution.”

“If there’s an incident tomorrow, it’s not going to solve it. So in the short term, we still need transit police officers, we still need UAPS to be on site, because they are a deterrent for any crime happening.”

While things in council got very divided and heated, Bid said that he thinks there can be a middle ground struck.

“The system is broken — the best way is to take the best of both worlds,” he said.

“So you’re going for harm reduction strategies, community-based strategies, but also take the good from what is working.”

He also emphasized that while things became tense between the ISA and the ISU during the meeting, he wants that to change.

“Our message to Indigenous students specifically, is that we are one, and we recognize all their experiences and what they have gone through,” he said. “We will make sure that international students who arrive to this country who are new are also educated in Indigenous history.”

“But we didn’t want this process to play out the way it did. Our prime motive was to advocate for international students’ needs. And during this whole process, I think things got escalated. And we didn’t want it to happen that way.”

Indigenous Students’ Union executives reflect on colonial history of policing

To help facilitate an equitable and safe interview process, a group interview was conducted with executives of the Indigenous Students’ Union.

When asked about the policy, Shannon Cornelsen said that the right balance was struck.

“The Students’ Union was very thoughtful in how much time and effort they put into consulting all the members across campus, and they tried to address all of the concerns while staying true to truth and reconciliation — and that’s a really major point for us,” said Cornelsen. “So without going back and going against the [Truth and Reconciliation Commission] Report, I think that this is the best solution that they could have come up with.”

The timeline of the policy may have been last minute, but this was more “student behaviour” than anything, said Shauna Stace, vice-president (finance).

“I think I heard a comment from the ISA that it was rushed, they did it on purpose, and people are busy so they wouldn’t notice that this policy would come out. I don’t think that was it, I think it was that they hadn’t completed their goal,” said Stace.

Chantel Akinneah, vice-president (internal), added that the council meeting left the ISA and the ISU in opposition.

“I think it’s a privilege that when you feel unsafe, you can turn to the police,” she said. “The international students, their stories resonated with everyone in the room, but they tended to make it seem like their experience is isolated.”

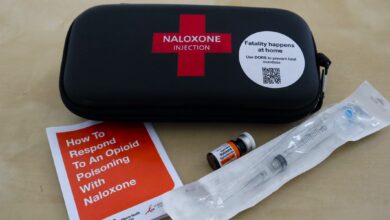

“We’re tackling the same problem, but the Indigenous people are also tackling the additional incarceration rates, stereotypes, and the opioid crisis — which all contribute to making the environment kind of hostile and unsafe.”

It’s not about us, per se, it’s about the future generations.

Shannon Cornelsen

The differences from that council meeting are still felt, Akinneah said.

“We didn’t leave on the same page and I don’t think we are still on the same page.”

When asked what the future of campus safety is, Cornelsen said it was education and groups on campus working together “in a gentle manner.”

“We’re having the same experience. It’s not any different. We’re all the same. However, sometimes those houseless people could be our family — and that just makes it more heartbreaking,” said Cornelsen.

Stace added that she did not see understanding of this in the council meeting.

“I think that the language used in that particular meeting, we’re calling them houseless people and vulnerable people and people we are afraid of in the LRT … [but] let’s not pretend that the majority of these people aren’t Indigenous,” she said.

“You know, these are our relatives.”

Followed by nods of agreement around the circle adding that the language used was hurtful and dehumanizing, Stace gave a tearful account of why the advocacy work the ISU does goes so much further than just campus and student issues.

“It hits close to home when you have relatives on the streets, addicted to drugs, because of intergenerational trauma,” she said. “That is not our fault. It’s not our fault. It’s not. It’s perpetuated by stereotypes. It’s perpetuated by lack of education. These are our lives.”

“And what we’re doing here is really important work when we’re representing and advocating for not just Indigenous students, but Indigenous peoples.”

Stace explained that because many Indigenous peoples do not have the opportunity to go to university, the ISU feels an obligation to advocate for the Indigenous community at large on campus.

“It’s our duty to protect how people view Indigenous peoples, in general and historically,” said Stace.

“We’re participating in these spaces because it’s the right thing to do for our people and it’s not very comfortable to have conflict. But if we have to stick our necks out and be uncomfortable to make it better for Indigenous peoples, then we will.”

“It’s not about us, per se, it’s about the future generations,” Cornelsen said, nodding in agreement.

Cornelsen said that what she would like to see going forward for campus safety is education, particularly for police and security. “I would like to see them take some Indigenous history, some training on why we do have that aversion to the heavily armed police and all of our policing issues.”

She explained that settler colonialism has been a historic problem that is still ongoing in Canada today.

“So I would like to just see a little bit more education, respectfully, because they are in Treaty 6 territory. And if we’re all educated, and if they know why some of these social issues are happening, then perhaps they can be a little bit more compassionate.”

Since leaving Edmonton, student who was stabbed at LRT transit stop last year feels “peace of mind”

In April of 2021, a U of A student was stabbed at the University LRT station. This student, who wishes to remain anonymous, was an international student from China. Recently, the man who stabbed the student has been given a 16-month sentence.

Regarding the sentencing, the student felt that the man who stabbed him did not receive an adequate sentence for what he experienced.

“I don’t know where the justice [is] if they don’t give a long enough sentence.”

However, the student noted that transit security has been a long-time issue for the city, recalling an incident before his stabbing where a Muslim woman was harassed on transit, which was one of many similar incidents.

Maybe [Edmonton’s] not suitable for me as an outlier. I do not feel included.

The student noted that during his incident, there was a transit worker present on the Corona LRT station who did not intervene or call security after the man yelled at him and followed him onto the train. Following his stabbing, bystanders who saw the incident happen on the train did not intervene or call for help. In an interview with The Gateway last year, he described the experience as “lonely.”

Now over a year later, the student says it was “ironic.” When he was attacked, the student was in his last week of a co-op opportunity where he worked for the Edmonton public transit system. He had also worked for the government’s pension plan.

“Everything made me feel like they just played a joke on me,” he said. “I tried my best to have passion for the public sector and they tried to ruin my trust.”

“Maybe [Edmonton’s] not suitable for me as an outlier. I do not feel included.”

Being so far away from home, this student was a captive transit user. In order to get to campus, he had to take transit every day. He noted that after being stabbed he saw comments online saying “because he’s poor, he cannot afford to get a car so it’s his fault tak[ing] the LRT at night,” which made him feel like the issue was not being addressed properly by the community.

He also felt that the university did not handle the situation properly, as he was told the LRT station was not university property, and UAPS could not respond to his situation or give him first aid on the platform.

“[It is your] duty of care, it’s your community member, it’s your staff, [and] students,” he said.

“I have to take transit to go to the U of A campus. And this happened in a campus area. So it could be addressed — rather than saying that is not my property.”

The student also felt that part of the reason why the incident happened and why transit safety is an ongoing concern is the lack of funding going into existing transit facilities.

“Although they’re expanding the LRT transit system [to] try to create more mobility and connected equitable communities, that is quite ironic,” he said. “Honestly, those bigger objectives trying to improve the communities’ prosperities failed, as safety is a fundamental thing.”

He feels that accountability needs to come from the municipal level, but other bodies like the U of A should also be pitching in to help improve transit.

When asked about the Campus Safety and Security Policy’s Second Principle 13 around community-based solutions to transit safety, the student noted that it “sounds very abstract” to him. Because there are no specific examples of how the UASU plans to go about their community-based approaches, he felt that he did not have enough information to make a judgement.

However, he was concerned about the advocacy against the Liaison Officer program. When the stabbing happened last year, the student had told The Gateway that he wished that UAPS could have responded to his emergency.

His concern is that advocating against the Liaison Officer program would slow down the response of UAPS, especially in response to emergencies like his. He mentioned that although UAPS did not perform first aid for him, the man who stabbed him might have “never be[en] caught,” if the university did not collaborate with the Edmonton Police Service (EPS) to share the footage of that night.

“I think the Students’ Union, especially the student groups, Students’ Council — they are very, very biased,” he said. “I don’t think [they] considered all the factors needed to be taken into account.”

“I think [the] Students’ Union or student representatives who are elected should be more sympathetic … to urgent or emergency issues.”

Since moving away, the student says he now feels “peace of mind.”

“[Edmonton] gave me good memories but [also] gave me a bad end for my university story.”

UAPS recognizes they haven’t “cracked the code”

While the position of student leaders across campus is not entirely united on campus policing, Marcel Roth, director of the University of Alberta Protective Services said their role on campus is to keep all people safe.

“We see our role as providing a safe environment for our community,” he said. “Our community being multilayered staff, students, faculty, contractors, [and] visitors.”

He explained that doesn’t mean he wants to maintain the status quo. Roth said he is aware that there are student concerns about UAPS and that this policy is hoping to address those. He expressed that he is looking forward to engaging with the new Students’ Union on the policy to re-examine the value they add to the community.

“There’s always room for everyone … to look at improvement, and we’re no different.”

That being said, there are a number of changes UAPS has made in their structure in the past few years. Roth explained that something they have been striving for is being more involved in the community through a Community Liaison Officer. This officer splits their time between residence life and UAPS for information sharing purposes and to answer questions students and staff in residence may have.

That didn’t just all come about, that was learned and absorbed through really watching and learning how the Edmonton Police Service and some other agencies deal with some of these social issues.

Marcel Roth

In addition to the Community Liaison Officer, there is also now a Community Assistance Team which consists of two officers that are intended to provide assistance to anyone on campus.

“It’s really focused on trying to provide them with the resources that they may need,” he said.

He explained that this team can be used to address a variety of things, but primarily substance use, housing, mental health, and finance, like assistance in obtaining government identification.

Roth said that UAPS looks to the Edmonton Police Service for increasing these community supports.

“That didn’t just all come about, that was learned and absorbed through really watching and learning how the Edmonton Police Service and some other agencies deal with some of these social issues.”

Roth spoke particularly of the EPS health unit, as an inspiration for UAPS’s approach to community outreach.

“We’ve learned a lot from what they do,” he said. “So [we are] very proud of that recent work, and the different way of doing business in the last couple of years.”

While EPS is a point of reference for UAPS, the two also collaborate and there is a dedicated member of EPS who works in the UAPS office called the Liason Officer. Roth said that the role is primarily about efficiency.

“So instead of placing a call through to the communications line, who then dispatches to patrol cars and southwest division in Edmonton, we have someone that can take many of those calls.”

Roth added that the role also has the added benefit of having a member of EPS who understands the issues of the university community.

While a plainclothes unit was something included in the policy as something the UASU would advocate against, and a question about it in the UASU survey, this appears to be based on a misunderstanding.

“UAPS does not have a plainclothes program,” said Roth.

While there is no plainclothes program or unit at UAPS, Roth explained there are very rare circumstances where officers may go out without uniform.

“I’ll give an example: we have a rash of bike thefts in a very specific location,” said Roth. “There are times that we have in the past, set up an organized approach to deal with that. And yes, on a very finite basis, that can include officers who are not in a uniform — that is about as far as it goes.”

The original plan for the community assistance team however, was that one would be without uniform.

“I would hazard a guess that that is probably where this topic of conversation came from,” said Roth.

The idea behind this was that some people may prefer or be more compliant with someone not in uniform, Roth explained. It does not mean that one of the officers would be able to go out alone without uniform.

“They’re working as a team together, they’re going to calls together, they’re driving a marked patrol vehicle together,” he said.

“It is far different than what probably comes to many people’s minds: that UAPS is sending out people … into the campus trying to blend in.”

Roth emphasized that UAPS is focused on continuous improvement. While they have equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) and mental health training in place, he recognized there are always ways to improve this to ensure it is not “checkbox training.”

“I will continue to explore new ideas that address safety … I don’t feel that we don’t feel that we’ve solved it or cracked the code in any way.”

City leaders announce funding for increased policing on transit in response to safety concerns

Edmonton’s city council recently approved a base budget of $407 million for 2023 for EPS. This approval comes after lengthy discussions about the city’s expenditures on policing. In the fall, the city will also be discussing a four-year budget.

Sarah Hamilton, councillor for ward sipiwiyiniwak and council-appointed commissioner for the Edmonton Police Commission, described the desire for more community-based solutions as “not surprising.” She acknowledged the increased demand for solutions aside from policing, or a “tiered response” that would address concerns about urgency and effectiveness.

“EPS is involved, and you need them to be [because] some of the events … they’re very violent, and that has escalated,” she said. “That’s a serious response, but there’s also stepped down approaches … [like] in terms of opioid responses.”

“This [transit safety issue] has escalated over the course of the pandemic, as the pandemic has increased inequity across the country in every jurisdiction, but we need to figure it out.”

She added that fighting discrimination from policing bodies has been a “huge focus.” Hamilton noted that while some issues with the EPS are solved through a disciplinary process, a restorative justice approach has been “well received.”

However, Hamilton explained that when restorative justice happens, there needs to be a level of accountability that she believes isn’t currently present in policing bodies of the city right now. For example, she highlighted that peace officers do not have a commission like the EPS does to hold them accountable.

“Our peace officers do good work and are often seeing a lot of the same stuff that police officers are but … the accountabilities aren’t always as transparent,” Hamilton said.

When talking about safety on campus, Hamilton highlighted that knowing your community can be a safety measure, as she noticed it worked for her mother and their neighbourhood.

“One thing that I noticed that we lack, regardless of [the] geographic communities that we live in, is that we don’t get to know our neighbours,” she said. “I think it’s harder in an urban environment and it’s harder on campus because people have more dynamic housing situations.”

“You might see somebody you never see again, but something I’d [ask] is how do you be a good urban neighbour [using] that bystander training?”

Following an incident on April 25 where a U of A hospital worker was pushed off an LRT platform, City of Edmonton Mayor Amarjeet Sohi announced that the city would be spending an additional $3.9 million to hire 20 more transit peace officers and deploy more social workers, increasing the total number of social worker and transit officer teams from two to nine.

“I am confident that having more peace officers on transit trains [and] LRT stations will deter people from engaging in some of the problematic behaviour that is causing disturbance and that’s causing safety issues,” Sohi said.

“That will definitely make students more comfortable when getting on transit.”

Hiring more police officers has been a point of difficulty because of long training times, Hamilton said. She also noted that it’s important for peace officers and support staff to ensure that the mental and physical health of responders is kept up.

In response to student concerns that peace officers have failed to or have not been permitted to act in emergency situations on transit, Hamilton said that having police is unavoidable.

“There are situations in which there is no more appropriate response than a sworn police officer and I think what has been highlighted is the need for more police officers.”

Sohi also acknowledged the concerns students had about the ability of different transit officers to respond to issues. To address these concerns, he mentioned that the city was looking into expanding the authority of transit peace officers. Additionally, the city also has transit security guards at stations. These security guards are neither police officers nor peace officers; Sohi explained that unlike the traditional notions for security officers, these personnel are eyes and ears on transit and act as deterrents to crime.

However, the solution to problems on transit aren’t just being solved by increasing security officers. Community-based solutions are also being explored by the city, among them being a daytime space led by Indigenous organizations where houseless peoples can be taken for “more culturally appropriate” services and programs.

“We are implementing solutions and we are working closely with the Edmonton Police Service as well as Indigenous partners from Bent Arrow Society and our city, working together,” Sohi said.

Despite not being a captive transit user, Hamilton emphasized that transit safety for post-secondary students would be a prioritized concern for council come fall when deciding what to do with the four-year budget. She urged those with ideas for the city and the future of safety and transit to bring them to city council during the budget’s public hearing process.

Policing and security on campus remains a divisive conversation, with multiple visions for how the university and transit system should look in the future. With so many suggestions currently on the table, how safety on campus is going to look is unpredictable — even in the short term. The only thing students can expect is for the situation to remain pliable, with strong voices advocating for students’ interests throughout.

While the UASU’s Campus Safety and Security Policy has passed, it is clear that the University of Alberta community remains somewhat divided on this issue. As this debate develops on campus parallel to the city-wide debate around policing, further discussion needs to take place to develop a more tangible, collaborative, and specific approach to safety and security for all.