Suppl

Suppl A University of Alberta research project is exploring the harrowing effects of permafrost thawing on water quality, land deformation and wildlife habitats.

For the past fifteen years, David Olefeldt, assistant professor in the department of renewable resources at the University of Alberta and Campus Alberta Innovates Program (CAIP) chair in Watershed Management and Wetland Restoration, has been conducting research on global warming and permafrost thawing.

According to Olefeldt, permafrost is any ground that has been frozen for two or more years straight, while in actuality, it’s been frozen for longer than that — usually hundreds or thousands of years.

On top of the permafrost, there is an active layer — the layer of ground that freezes and thaws every year.

Permafrost stores old plant material. Normally, plant material decomposes and turns into carbon dioxide, but when it is incorporated into permafrost, the plant material will stay undecomposed for a long time. When permafrost thaws, the plant material decomposes, which releases carbon into the atmosphere.

The release of carbon is the same greenhouse gases (GHGs) released from burning fossil fuels, like carbon dioxide and methane. As a result, this adds to the greenhouse effect, further warming up the climate.

For Olefeldt, permafrost poses a significant danger to our atmosphere.

“There is more carbon in permafrost than there is in the atmosphere,” Olefeldt explained. “So we’re asking this question with permafrost ground thawing so quickly and much of that organic material starting to decompose, how fast and how much of it is going to enter the atmosphere as GHGs and thus act as an accelerator to human emissions of GHGs?”

According to Olefeldt, the rate of decomposition changes depending on the type of plant material and how much of the matter decomposed before it froze up. There are also different types of soil with different amounts of soil carbon to consider, Olefeldt said.

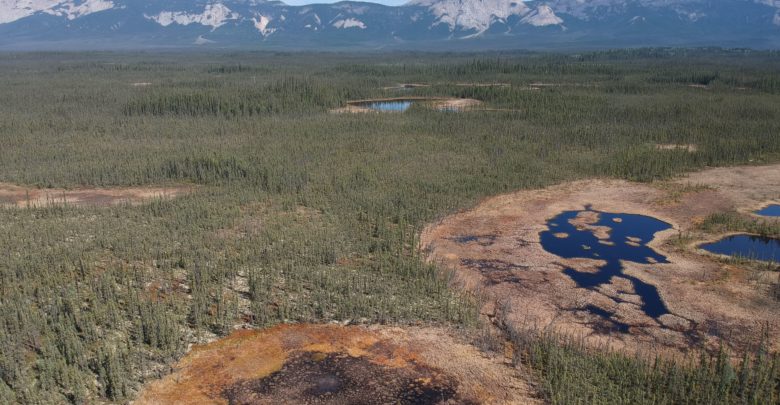

Olefeldt and his team of student researchers mostly study peatlands, which are wetlands with peat — old mosses that are not fully decomposed — soil on top. Because peatlands are wet and wetness reduces the rate of decomposition, Oledeldt discovered that these peatlands are thawing out and are becoming waterlogged or undulated, making peatlands the least risky at emitting GHGs. Although, when something is placed underwater, it will decompose anaerobically and would instead release methane, a more potent greenhouse gas.

“It’s a tradeoff if you put the organic matter underwater or not after it thaws,” Olefeldt said.

Permafrost thawing poses additional hazards, Olefeldt says

Olefeldt believes this permafrost thawing poses a massive threat to our world on many different levels.

“If we start comparing to human emissions of GHGs, we release about 10 pentagrams of carbon to the atmosphere and our current estimates of what the Arctic can do per year is up to about 10 percent of human emissions, which is our current upper limit,” Olefeldt said. “That’s more GHG emission than many large industrialized nations are releasing.”

It’s not only carbon in permafrost that is an issue, Olefeldt said, but also about how when it thaws it will affect water availability and water quality. When the ground thaws, water can move in different ways.

“It can infiltrate the interground water. [It can] move through soils that may have contaminants,” Olefeldt elaborated.

One of Olefeldt’s students is looking at mercury in permafrost and how thawing releases mercury into downstream ecosystems.

In northern Canada, all land is permafrost, meaning almost all communities are built on top of it. Some lands are more susceptible to deformation after thaw. For example, frozen bedrock is less of an issue, but when icy soil thaws, a deformation collapse called thermokarst is formed. As a result, many communities are at risk as houses start sagging and becoming damaged; Russia, Alaska and Scandinavia are some of the areas that are negatively affected by this thawing.

“A lot of Indigenous communities and cultures are based on practices on permafrost ground, so they’re all being affected by permafrost thaw,” Olefeldt said.

Another consideration is permafrost along the coast keeps the coastline firm. When that permafrost is thawed, it can lead to coastal erosion, so many communities are falling into the ocean, Olefeldt clarified. Roads begin to deform as a result of permafrost thawing.

Not only is this rapid thawing a danger to humans, but to animals, like Caribou, as well. The landscape changes due to global warming, leading to issues in the migration patterns of Caribou.

For Oledeldt, permafrost thawing is irreversible and the only way to help this problem is to reduce our emissions elsewhere so the Arctic doesn’t warm up.

“There’s nothing we can do to prevent permafrost from thawing in the Arctic,” Olefeldt said. “It’s all about how we are using fossil fuels.”