Helen Zhang

Helen ZhangAlmost as far back as I can remember, I’ve had issues with food. Whether I was eating too much, too little, or too much junk food, I’ve never quite been able to get the hang of eating a healthy, balanced diet.

This wasn’t really an issue for me until recently. I had a fast enough metabolism to keep up with whatever I threw at it, despite the fact that I’m allergic to the gym and I eat worse than anyone I know. However, after some time in university, things are catching up with me in a visible way.

The freshman 15 is not a myth. The scientific journal PLOS ONE published a study in July 2019 which concluded that during their first year of university in Canada, female students gained an average of four pounds, while male students gained eight. They also concluded that “during first-year university, both male and female students undergo unfavorable changes in nutrition.”

But why is this happening? Shouldn’t a large group of educated, driven young people be able to maintain a healthy lifestyle? There’s more to it than that.

Many factors can contribute to weight gain, perhaps most notably poor nutrition and lack of exercise, but there are other culprits too. Stress and sleep loss can also lead to weight gain, as both have been associated with hormonal imbalance and tendency to overeat. Sound familiar? I can’t speak for everyone, but I can honestly say that my first year of university was one of the most stressful years of my life, and I slept less than possibly ever before. During that short year, it can be hard not to feel like the whole universe is conspiring to make you unhealthy.

On top of being stressed out and tired all the time, many university students are buying and preparing their own meals for the first time. Figuring out how to make food can be hard in and of itself, let alone making that food healthy. And finding the time to cook wholesome, homemade meals? Forget it. You’ve got enough to worry about with that 3000-word Spanish paper due on Monday!

Chelsea Laronde, a fourth-year anthropology student, says she still struggles with making healthy choices on campus, where she has lived in residence since her first year. “A lot of [undergraduates] don’t have a private kitchen they can use, and it’s very time-consuming to plan healthy meals. I eat the most at Starbucks. After every single class that I have in the same building with a Starbucks, I will go get Starbucks.” She goes on, “It’s probably more expensive to eat out like I do, but for convenience sake it’s worth it.”

All of these factors work against students trying to maintain what might’ve been healthy lifestyles. Even going into university with an admittedly unhealthy lifestyle, mine only got worse than it already was.

Robyn Adelman, a fourth-year Kinesiology student majoring in physical activity and health, puts much of the blame on the nature of university itself. “University in general isn’t exactly set up for the healthiest of living styles,” she says. “We spend two to eight hours in classes a day sitting, and then the rest of our time sitting and studying… coupled with the lack of healthy options on campus, it can be really difficult to balance your time to grocery shop or prepare meals for yourself.” She’s right. There are many more options for fast food on campus than there are healthy options, and even those are usually further away and more inconvenient to go to. If I have a class in Humanities, I’m far more likely to just grab A&W or Subway from HUB mall than I am to walk to Van Vliet and get Chopped Leaf.

Time and a sedentary lifestyle are things many university students tangle with. But even more difficult to balance than those things, perhaps, is money.

Yes, the big dollar sign. The age-old struggle between university students and their own empty wallets is well-known and highly satirized. Even in more serious films, like the recent J.R.R. Tolkien biopic, students grapple nearly constantly with debt, finances, and trying to balance the cost of studying with the cost of living. If you go to school full time, it can be difficult to offset these extra costs with a job.

“Most students aren’t working,” Adelman says. “If they are it’s in a really limited capacity, making minimum wage, which is enough for like a meal a day… Like, do I want to sleep and not work tonight? Or do I want to take a student loan out and then have to pay it back?” This is partially true; Statistics Canada posits that over 50 per cent of post-secondary students have jobs, but that number includes freelance and part time work. So while most students are actually working, the perceived full time income still isn’t there.

In large part, we can do nothing for the state of our finances. If, like me, students are self-reliant all the way through university, they will invariably face the same question more than once: do I buy the healthier, more expensive option, or do I choose the unhealthy, less expensive option? Almost every single time, they’re going to choose the cheaper option. If I have to choose between spinach and paying my heating bill, I’m always going to choose heat.

This is a common struggle — so common in fact, that it has become a widespread inside joke among students. From personal experience, I can assure you that students don’t want to eat ten-cent ramen noodles for dinner every night, but sometimes we have to.

“The college experience is all about junk food,” Laronde says. “All the memes are about college eating, and going home and having a home-cooked meal that isn’t from a can or a plastic package. That’s like the number one thing everybody [makes] jokes about.”

But not all of us are gaining a so-called “freshman 15.” Some of us are losing it, and not in a healthy way. A recent study conducted by Temple University and the Wisconsin Hope Lab concluded that 36 per cent of college students in their survey weren’t getting enough to eat. Not eating enough is just as bad — if not worse — than eating too much. But the problem concerning a lack of food doesn’t stop there.

College campuses have become well known over the years for being breeding grounds of mental illness. Burgeoning adulthood, frequent drinking, stress, and other factors all contribute to things like a heightened rate of alcoholism, drug addiction, and mood disorders. Alongside all of these is an increased risk for eating disorders.

“I skipped out on so many family events and social events with my friends. Anything that involved food, I was terrified to go.”

Eating disorders— specifically anorexia nervosa, which causes sufferers to chronically restrict caloric intake and exercise to the point of exhaustion— have long been cited in the DSM-V (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, used by professionals to diagnose mental illnesses) as the most deadly type of mental illness, with about one in five sufferers dying within 20 years of diagnosis. The National Eating Disorders Association, or NEDA, conducted a survey between 1995 and 2008 to study the prevalence of eating disorders on college campuses. Shockingly, they found that the incidence of anorexia in males increased from 7.9 to 25 per cent, and 23 to 32 per cent in females during that time. The national rate of anorexia is between 0.3 and one per cent, according to Statistics Canada.

There is a huge gap between the national average and the average among university students. It could have something to do with the average age on campus, but it’s likely more than that. Adelman, who opened up about her ongoing struggle with disordered eating, says, “I skipped out on so many family events and social events with my friends. Anything that involved food, I was terrified to go.” She goes on, “I see all these [people], women especially, doing the exact same thing I was [doing] two years ago.” Adelman wonders how the situation got to this point. “Like, none of us are stupid. We’re all in university. We for the most part know what we’re doing.”

Laronde describes it more broadly. “I feel like it’s very [true] that a lot of students go through some form of body dysmorphia,” she laughs uncomfortably. Body dysmorphia, or Body Dysmorphic Disorder, is a condition characterized by a strong dissatisfaction with some aspect of how a person looks. Those who are affected often spend hours obsessing over perceived flaws, even when those flaws are so insignificant no one else would ever notice them, or outright imaginary. Depending on the person and which particular flaws they’re obsessed with, body dysmorphia may lead to the development of an eating disorder, and is almost always present in cases where an eating disorder already exists.

Having struggled with an eating disorder myself, it was an odd experience walking around campus with so many clearly disordered men and women while I carried a relatively clean bill of health. I suppose it was easier to resist the temptation of falling back into old habits for me because it’s been years since I was labelled “recovered,” but I still felt the pull. It seems like everywhere you go on a college campus, droves of men and women are overeating or obsessively exercising and restricting their calorie intake, and no one intervenes. Perhaps this too has an effect on the sky-high frequency of eating disorders in college students.

NEDA says that “screenings for eating disorders on campus are seriously lacking.” In my own experience, despite meeting many individuals who might qualify for having an eating disorder, I have never come across someone who was offered help for it. This might be because of the university’s lacklustre mental health programs, which exist but are inaccessible or unknown to many students (and are always a topic of contention during election season), or because of the stigma surrounding eating disorders in general.

So time, money, stress, sleeplessness, and mental health all contribute to poor nutrition in university students. But what can we do? How do we fix the unfixable?

“I think the biggest thing that will make the biggest difference in someone’s journey is having a supportive network,” Adelman says. “Not all of us have the time to spend in the gym or the money to get a personal trainer or nutritionist. That can be a barrier to access for a lot of people, which sucks, but there’s tons of information online, and it’s just about making a commitment to yourself.”

“There are a bunch of affordable options on campus in terms of physical activity,” Adelman goes on, “but the awareness on campus of those opportunities isn’t super well-known. Your gym membership in VVC is included in your tuition for most students.”

Many students seem to be sacrificing their physical and mental health in favour of their grades, which isn’t good, but it is understandable. Tuition is the highest it’s ever been. According to Statistics Canada, in the 2018/2019 academic year, tuition increased for Canadian students 2.4 per cent on average. Canadian undergrads pay an average of $6,463 per year and international undergrads pay $17,744. Most of us can’t afford to waste our time here.

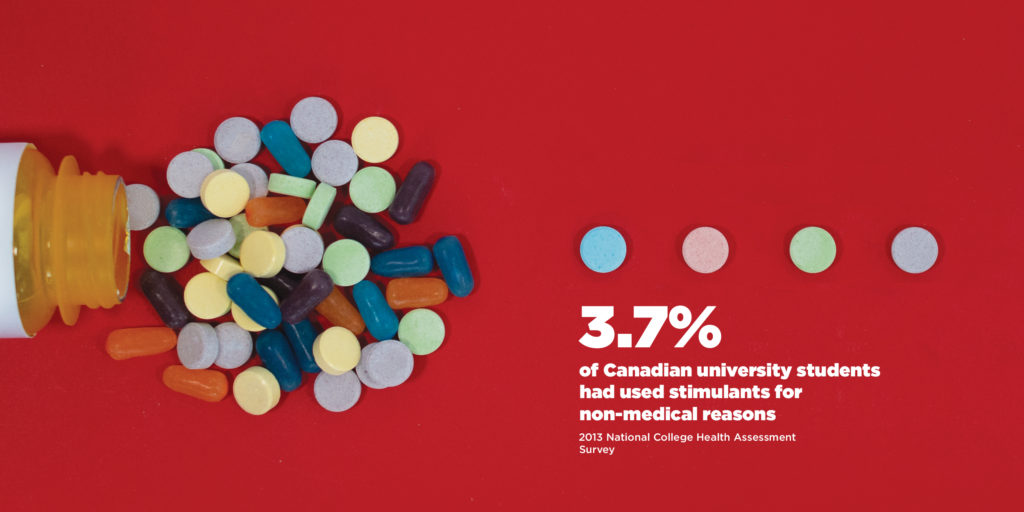

Even drug abuse has become a meme among students. Adderall, a synthetic mood-stabilizing drug, has been used so frequently to combat sleep deprivation and inability to concentrate that TV shows have written it into their storylines. grown-ish, a spinoff of the popular sitcom black-ish, prominently featured the main character’s struggle with the drug during its first season. The Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse conducted a 2013 study which found that youth (15 to 24 years of age) had the highest prescription stimulant use in Canada, at 2.6 per cent, compared to the general population average of 0.9 per cent.

Additionally, the spring 2013 National College Health Assessment Survey found that 3.7 per cent of Canadian university students had used stimulants for non-medical reasons in the past 12 months. While that study was not representative of all students in Canada, other studies conducted on individual campuses have found that up to 5.9 per cent of the student population engage in these behaviors. Ironically, being an amphetamine, Adderall is also an appetite suppressant whose chief side effect is weight loss.

The list of problems students face when trying to maintain or gain health only gets longer the more you think about it. First it was only unhealthy eating, then lack of exercise and sleep, then increased risk of eating disorder and now amphetamine abuse? How can we solve all these issues?

It just isn’t that simple. All of these problems on their own are complex, and require many steps to right. When combined, they’re like a hurricane of poor health and nutrition that students are lucky to escape alive. It’s a lose-lose situation; you take care of your health while your grades suffer, or your health suffers while you watch over your grades. If you try to take care of both, it isn’t long before you burn out and both health and grades suffer.

All of these problems on their own are complex, and require many steps to right. When combined, they’re like a hurricane of poor health and nutrition that students are lucky to escape alive.

I strongly agree with Adelman’s assessment that we need better support networks. Students are often away from home for the first time in their lives, their only company being other students who are trying to find the same balance as them. We need to provide more support to them, because they clearly and statistically need the help.

“You need to do well in your studies,” Adelman says, “but it’s often at the detriment of your physical and mental health, which are very closely tied.” So we’re still between a rock and a hard place.

Despite all the grim statistics and issues students are facing down in the modern age, there is hope. Many universities, one being Guelph, have created student support groups on campus for people who might be struggling with their mental or physical health. The University of Alberta has the Sexual Assault Centre, which helps to relieve yet another issue in the maze that is the student experience. If you ever find yourself struggling to afford meals, the Campus Food Bank is also a wonderful place to go, and the Peer Support Centre, as the name suggests, offers peer support, crisis management, and is a place where students can go if they just need to talk.

Though we are working towards easier navigation of college life, we still have a long way to go until we are healthy, happy human beings. Until then, the best we can do is strive to be better than we have been. Take the stairs, go for a walk, swap out your Starbucks coffee for a bag of carrots. If you have, or are even suspicious you’ve developed an eating disorder, you should speak with a healthcare professional. Friends and family are important support pillars too, no matter how far away they live. Chances are that they care enough to help you get help. If you feel your health is in danger, you shouldn’t be afraid to take steps to improve it. Ultimately, our health is our own responsibility, and we need to take control of it before it can begin to get better.