Stages of recovery: Edmonton’s theatre community responds to #MeToo

Richard Bagan

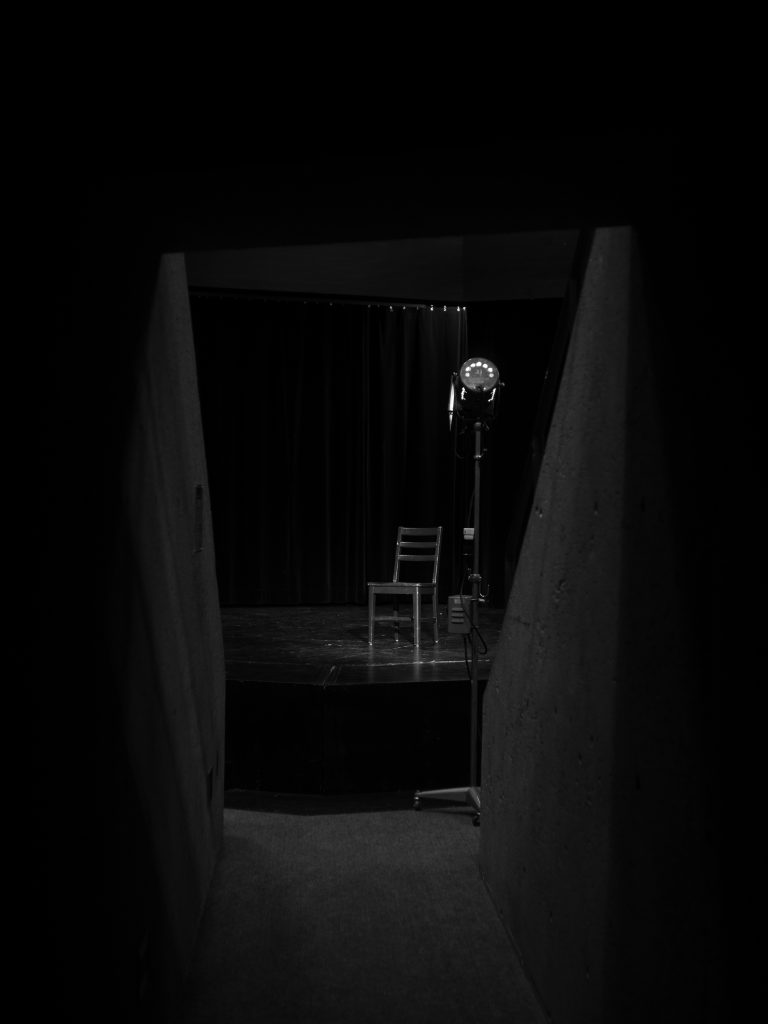

Richard BaganBack in spring, before summer festivals and fall papers, I found myself in the Westbury Theatre at the ATB Financial Arts Barns. This in itself wasn’t unusual, since the Westbury is one of Edmonton’s major theatre venues. What was unusual was that I sat onstage, in a circle of chairs, surrounded by other male theatre artists: actors, artistic directors, veterans of the craft. I was the youngest one in the room.

It was May 23, 2018, and the Theatre Edmonton Project, a grassroots coalition of millennial theatre artists, had organized “Curtain Up: A Meetup for Male Identifying Members of the Edmonton Theatre Community.”

Led by Derek Warwick from the University of Alberta’s Sexual Assault Centre, the men in attendance discussed their experiences surrounding harassment and assault in their profession. The older artists looked back on how far we’d come, while the younger men looked ahead to how far we have to go. Gnawing questions and fraught emotions filled the circle.

Hours later, the discussion gave way to silence: Brooke Leifso, a crip theatre artist and master’s student in expressive art for conflict, transformation, and peacebuilding at the European Graduate School, led those remaining in a workshop using visual art to reflect on the thoughts and feelings Warwick’s workshop had stirred in them.

But these feelings were nothing new — the theatre community had spent the professional season reeling from revelations of #MeToo. And many who had kept quiet about harassment and unwelcoming environments in their careers had now begun to speak up.

“I’m seeing in the theatre community a want for practical skills to make change,” Leifso told me later. “What I hope for is an increased sensitivity of how to build safe creative spaces for everyone and avoid the pitfalls of toxic power dynamics no matter how they [arise].”

When I met with Leifso in a downtown café a month later, the mood was palpably different. The summer sun shined down on us and our coddled eggs as we discussed the artistic community we both love — the same community that we had witnessed unravel since October. “The theatre community is particularly ripe [for change], because it’s a series of people who really want to do well,” Leifso said. “So how can we build places for compassion and reflexivity?”

In 2006, activist Tarana Burke coined the phrase “Me Too” to support survivors of sexual violence. Eleven years later, on October 5, 2017, The New York Times published a story reporting several allegations of sexual harassment against Hollywood film producer Harvey Weinstein. The Times’s report spanned decades of alleged misconduct. On October 15, 2017, actress Alyssa Milano tweeted: “If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet.” The response was overwhelming.

Soon enough, people the world over — mainly women — began using #MeToo on social media to share personal stories of sexual violence and calls for justice. Meanwhile, several other men in media and politics were publicly accused of sexual misconduct, including Kevin Spacey, Louis C.K., and James Franco. But #MeToo didn’t only affect global industries — it reverberated on a local level as well.

As the hashtag became a movement, Edmonton-based playwright, filmmaker, and performer Chris Craddock used it in a personal Facebook post. What followed, however, was not a story from the receiving end of sexual violence, but a confession of being its perpetrator. Craddock said he had touched without permission and acted as though women were objects, and that he was horrified to realize it.

Days after Craddock posted his confession, Rapid Fire Theatre (Emonton’s leading improv company) cut ties with the now infamous artist, who had once been its artistic director. In an open letter signed by Rapid Fire’s current artistic director Matt Schuurman, general manager Karen Brown Fournell, and president Amir Reshef, the company said it would not work with “identified predators,” including Craddock.

When I called Schuurman, he was reluctant to dredge up the pains of the past. As he noted, these events were emotional, painful, and traumatic for a lot of people. But the company has worked to heal from its wounds.

Now over a year out from the scandal, Rapid Fire has reviewed and publicized its policy against harassment and discrimination — and Schuurman stressed that it reviews its policies on an ongoing basis. The company has also created a form to report incidents of inappropriate behaviour, with the option to report anonymously, and offers new consent and bystander training annually.

“Creating safe spaces is not just a checkbox,” Schuurman said. “It’s constantly evolving… You have to make it part of the culture of your organization, to always be cognizant of it and always be working on it.”

Since improv is spontaneous, performers aren’t able to plan carefully in advance. This can lead to misunderstandings or unwelcome surprises onstage. A few years ago, Schuurman introduced check-ins for performers to let each other know what they’re comfortable with doing in that night’s show. After October 2017, Rapid Fire made this an expectation.

“When you have clear boundaries, you know how far you can go, rather than guessing and being vague about it,” Schuurman said. “These conversations only make us stronger; they don’t hold us back. They in fact propel us forward… That makes for healthier performers, better performances, and better art.”

Three floors above Rapid Fire’s home in Zeidler Hall stand the offices of the Citadel Theatre’s artistic director, Daryl Cloran, and executive director, Chantell Ghosh. The hallways are plastered with posters from bygone productions. Ghosts of plays, performances, and events haunt this venerable building — and mingled with them linger the phantoms of bullying, hurt, and trauma.

“The theatre, quite possibly because of the intimacy and vulnerability of the creative process, was maybe more susceptible [to workplace bullying and violence],” Ghosh said. “When things went bad, they went bad bad.”

Early in Cloran and Ghosh’s tenure, a number of artists and staff approached them about experiences of feeling unsafe in the workplace. When common themes emerged in these stories, the two approached the Citadel’s board of directors to consider taking action. On March 13, 2018, Cloran released an open letter about the dark history of his company. The letter said that, at times, the Citadel has been a negative workplace for artists and staff, and that this is unacceptable. In the months that followed, Cloran and Ghosh met with artists who had felt alienated from the Citadel due to harmful experiences in their past. They provided opportunities for artists to return to the Citadel space after feeling unwelcome there.

As per the letter, the company retained Wade King, a human rights and disclosure advisor, to implement a safe disclosure process. Due to the confidentiality of the process, Cloran and Ghosh said they couldn’t give specifics on the events described or name the alleged perpetrators.

But, Cloran said, they took the lead from community members who wanted to resolve the harms of the past and move onward into — hopefully — more positive futures. On May 14, 2018, the Citadel hosted a gathering for theatre community members to discuss their experiences. For Cloran, this event was an important healing moment — one he hopes will precipitate a stronger spirit of openness and fellowship in the theatre he now runs.

“[For me, theatre involves] building art in a manner that is about the group creating something great, as opposed to an auteur director who comes in and breaks or demands things,” he said. “It’s a shift in the belief in how great art can be made.”

On an institutional level, the Citadel has hired a human resources specialist, which it didn’t have before. It’s also implementing training for managers to deal appropriately with their employees, especially in the high-pressure situations of theatre. The company is participating in the Canadian Actors’ Equity Association’s “Not in Our Space!” program, which aims to help artists address concerns with industry harassment.

On January 9, 2019, the Citadel published a report on these efforts. According to the report, the company has piloted a “360 degree” anonymous evaluation process for staff to communicate feedback and issues with management to the Citadel’s Board of Directors. Going forward, actors and other community members will help review this evaluation system. The company has also reviewed its policies on child chaperones and open rehearsals to be “proactive about best practices.” The Citadel plans to release new reports on at least an annual basis to “continue the conversation” about its workplace environment.

To follow up on these initiatives, the company hosted another community event on February 11, 2019, where six leaders in Edmonton’s theatre community discussed their best practices in creating welcoming spaces for artists. Approximately 20 people were in attendance.

In the future, Ghosh hopes the Citadel’s staff will be well-equipped to handle workplace problems and will have a reputation across Canada for being a place of “excellence and openness.”

“It’s not paperwork, it’s ‘people work,’” Ghosh said. “If you stay vigilant and keep having these conversations, that is the only way you’re going to gradually shift culture.”

At first, Heather Inglis didn’t quite believe the Me Too movement would lead to substantive change in her industry. But as the artistic director of Theatre Yes, an Edmonton-based “boutique” theatre company, she began to see a cultural shift when institutional leaders like Schuurman made statements in response to what had previously been only an online phenomenon. “I was shocked that there were colleagues of mine who had behaved poorly for whom there were consequences,” Inglis said. “That was not something that I had ever seen before.”

For Michelle Robb, a U of A BFA acting student and emerging playwright, the revelations regarding Chris Craddock likewise struck her as a turning point. As #MeToo hit the theatre community, Robb was heartbroken. She used to look up to some of the individuals who were outed, though as a younger artist, she admits she’s largely in the dark about their alleged wrongdoings.

“I’m hearing that usually male artists who I used to look up to have done bad things,” Robb said. “I want to know what the bad things are!”

I worked with Inglis and Robb in the Citadel’s Young Playwriting Company while #MeToo was trending, and we often mulled over these ruptures in our theatre community in the company’s boardroom.

In Inglis’s view, the Citadel is doing good work to get to the bottom of the “psychological bullying” of its past. But, Inglis said, the ingrained psychological basis of sexism and bullying requires vigilant, constant work to combat. Robb is unsure how far these efforts can go — especially since all public statements have been unspecific due to confidentiality.

“Is it adequate? I don’t know what would be adequate,” Robb said. “Is it as bad as they’re making it sound? Is it worse? The language around it is hard to navigate when you’re addressing a public that’s both full of people who are in on ‘the dirt’ that’s been happening and people who are just entering the scene.”

Inglis said a lot of the men who were called out in the past year have been “exiled,” and their careers are over. Craddock, for instance, has disappeared from the theatre community. Robb commented that this can have severe psychological effects.

In Inglis’s view, we need to ask questions about what appropriate responses to crimes and social misdemeanors are when they’re occurring in public culture, not in the legal system. For her part, Robb wishes there had been more acknowledgement with #MeToo that “we don’t know the right answer” to rectifying or retributing harms. Considerations of mercy, Inglis said, appear in ancient texts throughout the world. “People are complicated,” Inglis said. “They’re good and they’re bad: everyone.”

High-profile cultural commentators, including Canadian author Margaret Atwood, have voiced similar concerns. On January 13, 2018, Atwood penned an opinion piece in The Globe and Mail called “Am I Bad Feminist?,” saying #MeToo is “a symptom of a broken legal system” and that we need to ask what will come next. Atwood borrowed the term “bad feminist” from the American writer Roxane Gay, who coined it to describe being a feminist while enjoying things that may seem at odds with feminism. In response to Atwood’s piece, Gay tweeted, “Actually, Margaret… with all due respect, this isn’t what I meant by Bad Feminist.”

Gay, along with other feminist figures, has criticized Atwood’s line of thinking. On October 5, 2018, Gay wrote in The New York Times that “Despite everything we know about the prevalence of sexual assault and harassment, women are still not believed. Their experiences are still minimized. And the male perpetrators of these crimes are given all manner of leniency.” The rhetoric that men have unduly suffered due to #MeToo, Gay claimed, downplays the experiences of women. Instead of reserving empathy for male perpetrators, Gay said we should focus on empathizing with and supporting female survivors. “The bar for a man’s ruin is, apparently, quite low,” Gay wrote. “May we all be so lucky as to have our lives so ruined.”

Robb is exploring these themes in her play Tell Us What Happened, which is currently in development with Theatre Yes. The play follows a group of girls living together in Edmonton who run a Facebook group for “girls to go on and talk about their girl struggles.” At the start of the play, some of the girls in the Facebook group realize they’ve been sexually assaulted by the same guy — and that guy is the best friend of the group’s founder. The girls’ lives are fractured as they question how to lead when the group’s stories become personal.

“I wanted to see if I could find out what the right thing to do would be if that were to happen,” Robb said. “And I wanted to demonstrate how hurt girls can get at such a young age. I really feel bad for my characters since they’re forced to grow up a lot faster than they should.”

Robb began writing the play in September 2017 — before the Me Too movement began in earnest. Robb isn’t sure if the play would be different if #MeToo hadn’t happened, but the event catalyzed discussion whenever she brought the play in to workshops. In Robb’s current draft, the script makes no reference to #MeToo; she wants the events of the drama to hold up regardless of the cultural moment in which they’re staged.

“I don’t believe that a hashtag is what started this movement,” Robb said. “I think a hashtag is what made this movement visible.”

The play will premiere in Theatre Yes’s 2019-20 season as a co-production of Theatre Yes and The Maggie Tree, an Edmonton-based independent theatre company focusing on developing works by, for, and about women. For Inglis, Tell Us What Happened answers a need for artistic commentary on the cultural explosion that #MeToo precipitated. Inglis said the play fits her company’s mandate of “intelligent theatre for adventurous audiences.” Since Robb is a young woman playwright, she is, according to Inglis, uniquely positioned to talk to her peers about these topics in an intelligent and complicated way.

“I think it’s our duty as artists to create conversation and dialogue about what’s important in our world,” Inglis said. “And Michelle’s play very much fits that bill.”

Inglis hopes the women of Robb’s generation have healthier work experiences in theatre, and that they get more work as playwrights, directors, and leaders.

“I think [the move to a post-#MeToo future is] going to be slower and stranger than we can possibly imagine,” she said. “I do hope that we can give people the benefit of the doubt for trying hard to do their best.”

In an emailed statement, Leifso said she has stopped doing workshops for the professional theatre community because, while the people in power do want change, they don’t necessarily want to individually change. “The change required could topple the system currently built, starting with educational institutions,” Leifso wrote. “People before art.”

Ultimately, she hopes we can not only combat harmful actions on an individual level, but oppression on a structural level. Efforts to call this future in from the wings may be fraught with alienation, contests for dominance, and generational and gender-based divides — but like Inglis and Robb, Leifso is hopeful.

“I’m so curious to see how we move forward in the future in a way that has greater sensitivity,” Leifso said. “How can we hold complexity for each other?”