Supplied

SuppliedUniversity of Alberta professor Irene Cheng and her team have recently developed a system to predict natural and man-made disasters using artificial intelligence.

Cheng, a professor in the department of computing science, worked on the project with three of her graduate students and 3vG, a Vancouver-based company. The collaboration began nearly 19 months ago and is the first space project to be funded in western Canada by the Consortium of Aerospace Research and Innovation in Canada (CARIC).

Cheng was initially contacted by the CARIC director, who meets with industry and academics to establish collaborations to potentially fund. She then contacted 3vG, a company that uses satellite technology for ground movement monitoring for their clients. 3vG currently surveys for potential damaging ground movement around mining sites, pipelines, and infrastructure.

“The good thing about universities working with industry is we have the methodology and technology, but they have the expertise and application, so this kind of collaboration is really wonderful,” Cheng said.

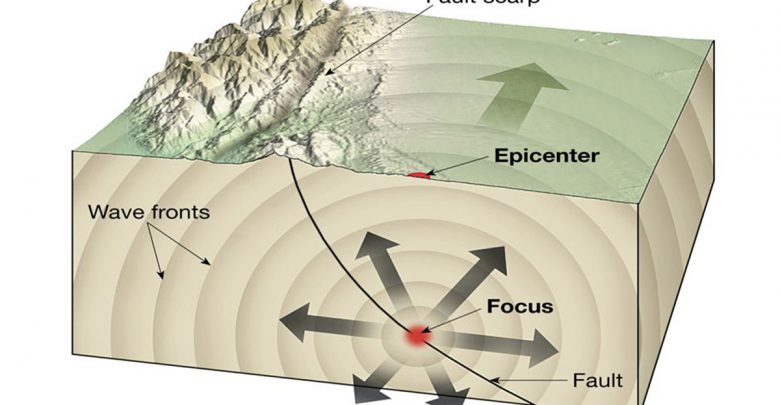

The company’s technology is based on radar, which emits radio waves down to Earth from a satellite and detects changes in the reflected wave as a result of ground movement. This allows monitoring of shifting ground areas which are then studied to predict natural or man-made earthquakes or landslides.

“The impact of that kind of information can be huge,” Cheng said. “These days we talk about energy, the environment, extreme weather, infrastructure. All these things have something to do with ground surface.”

Currently, these satellites must circle Earth 30 times, generating enormous amounts of data. Once that information is gathered, experts then sort through it to inspect the quality of the data. This is a complex, time consuming, and error-prone process, which has meant it can take roughly six months for predictions to be made.

Cheng’s team’s expertise in artificial intelligence was sought to develop a machine learning program to automate and improve much of the process. As a result of their work, predictions can now be made in only one month with as little as one satellite flyover.

For Cheng though, this isn’t the end of the road. She believes the satellite technology, now equipped with her machine learning program, will allow for even more applications in the future, including predicting volcano eruptions.

“There’s a lot of applications we can tie into this model, so we’re pushing [artificial intelligence] out because… it can be applied to a wide range of applications,” she said. “It’s not easy, we haven’t solved some problems, but we have done advancements.”