Behind closed doors: A hidden legacy of animal experimentation

An investigation into animal testing at the U of A

Laura Lucas

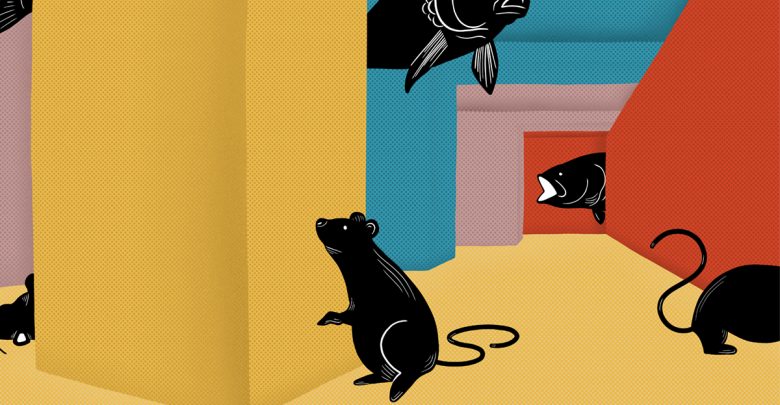

Laura LucasJyoti Singh, a fourth-year physiology student, presses a cold metal scalpel into the soft flesh of a newly euthanized lab rat. The sharp edge pierces the skin with little resistance as warm blood trickles down her purple nitrile gloves. Singh must work quickly but delicately as she separates the hind legs from the rest of the body. From there, she can isolate the saphenous nerve that relays sensory signals from the foot to the spinal cord. She believes that diabetes might impair this nerve connection. To test her hypothesis, she must extract the nerve intact; the slightest tear or the softest pinch could damage it and render the rat’s sacrifice meaningless.

Singh is one of dozens of researchers at the University of Alberta who use animals for biological research, a practice that has been legally recognized since the 1870s. According to a 2005 study from the journal Alternatives to Research Animals, an estimated 115 million animals are used in medical experiments every year. Singh has cut open more than two dozen laboratory animals in the past four years. The U of A’s animal facility is practically her second home; the animal care technicians are much like her second family.

“Not everyone is comfortable using animals in research. It’s definitely a difficult topic to tackle,” Singh says. She’s worked with both mice and rabbits, but settled with Nile grass rats because of the way they experience diabetes. By placing them on a high fat and low fibre diet, the rats develop insulin resistance within the first two months. With time, the rats experience all five stages of type 2 diabetes, similar to a human patient.

“When I first got the rats from our research collaborators they were already 18 months old, so they were really fat. They had eye problems, cataract problems, and organ failure. Because of how diabetic they are, some rats develop liver tumours and we see toxins accumulate in their urine,” Singh says. “They’re really sick and it can be hard to watch.”

This is the reason she refuses to name her rats anymore. In her line of work, she can’t afford to be sentimental. Though it’s never easy watching an animal suffer, Singh insists that if society wants better treatment for diabetic patients, it’s the price that has to be paid.

“To study how a disease works we have to induce it in an animal, otherwise there’s nothing to study,” Singh says. “That’s what the ethics guidelines and the protocols are here for, to ensure that it’s being done in a way where the animals are in the least amount of pain possible.”

Prolonged exposure to high blood sugar can cause nerve damage, leading many diabetic patients to lose sensation and motor control in their arms and legs. Because most nerve cells can’t be replaced when they die, Singh’s research focuses on finding ways to retrain surviving nerve cells to take over the jobs of their deceased counterparts. Using diabetic rats as a model, she has found that blocking select protein activity in surviving nerve cells can encourage them to fill in for damaged cells. Now, Singh is looking to test drugs that can target these proteins and improve motor control in rats with severe diabetes and other neuropathies. She hopes her research will one day benefit those suffering from diabetes and other neurodegenerative diseases. “Either you can do this type of research or you can’t,” Singh says. “In the beginning, I used to get quite emotional, but now I’ve stopped feeling.”

95 different institutions in Canada use animals in their research programs, including major Canadian universities such as the University of Toronto, McGill University, and the University of Alberta. However, there are no legislations or policies in Canada requiring any of these institutions to release statistics on research animals. The nature of the animal’s role in medical research and the experiences of the animals themselves remain behind closed doors.

“Most students are not aware, unless they’re directly involved in those research projects, how animal experimentation takes place at the U of A campus,” says Susan Hamilton, one of the U of A’s associate vice-presidents of research. Hamilton’s area of specialty is the humanities and social sciences. To understand the reason behind this lack of transparency, Hamilton has dedicated her career to studying 19th century scientific literature, when physiologists would dissect human and animal bodies to understand how they worked.

Animal research was brought into England from neighbouring countries in the 1870s. In 1873, Scottish physiologist David Ferrier published a paper on cerebral localization while working at King’s College Hospital. Splitting open the skull of a living monkey, Ferrier applied electrical stimulation to various regions of the brain to map out its function. Universities began training students on the topic, and animal labs could receive government funding.

Then in August of 1874 at a British Medical Association meeting, French physiologist Eugene Magnan injected absinthe into dogs to induce epilepsy to educate the audience on the adverse effects of alcohol. The account was reported in Animal World that summer, a journal published by the Royal Society for the Prevention of Animal Cruelty. In the article, Frances Power Cobbes, founder of the world’s first anti-vivisection organization, argued that these experiments posed a moral danger to society. In 1875, Cobbes advocated for the regulation of animal use in medical research. In the summer of 1876, the Cruelty to Animals Act was passed.

“The act eventually comes to be known as the vivisectors charter,” Hamilton says. “It was supposed to be an anti-cruelty law, but it in fact facilitated scientific experimentation because of the administrative process that comes into being.”

Under the Act, scientists no longer had to disclose their use of animals to the public, and instead regulated themselves. The number of animal experiments in Britain more than doubled by the end of 1876. This legislation set the framework for other countries looking to regulate animal experimentation.

In Canada, animal experimentation was formally regulated in 1968, when the Canadian Council for Animal Care (CACC) was established. The CCAC is Canada’s organization for oversight of animal ethics and care; it enforces a licensing and inspection system for all animal experimentation. For most Canadian universities, including the U of A, ethics approval comes from internal animal care and use committees, which operate under CCAC guidelines.

At the U of A, animal care and use committees are made up of 12 to 13 members each, composed primarily of scientists such as department chairs, faculty members, post-doctoral researchers, and graduate students. By Alberta law there must be a veterinarian present, and by CCAC requirements, at least one layperson to represent the Canadian public. For a research project to receive ethics approval, all members of the committee must vote yes, otherwise, the proposal is sent back for revision.

Complaints from modern-day animal rights groups maintain, however, that there is a problem when it comes to the inaccessibility of animal research statistics. Each year, the CCAC publishes blanket statistics summarizing the total number of research animals used in Canada. In 2016, 4,308,921 animals were reported as being used in scientific research, with the top three species being fish, mice, and cattle respectively. But like the UK, Canada does not require institutions to publicize details of animal experiments. This means the exact number of animals used at any specific Canadian university, and the nature of the experiments they’re used for, are rarely disclosed. For Hamilton, this comes from the lack of transparency legislated in the 1870s. But for those in the CCAC, the figures are hidden simply to avoid potential misinterpretation.

In 2016, fish replaced mice as the most used research animal in Canada. The jump from 1.2 million fish in 2015 to 1.6 million fish in 2016 was interpreted by many animal rights activists as a dramatic increase in fish dissections. But Craig Wilkinson, a U of A veterinarian and member of the CCAC’s public affairs and communications committee, explains that this wasn’t the case. The majority of these fish were kept for breeding purposes. Scientists needed embryos and eggs for genetic studies like adding and removing genes to observe how cells behaved in a developing organism. Adult fish were rarely experimented with.

“Things like this take quite a long time to explain and a lot of institutions have these types of nuances,” Wilkinson says. “Because universities are concerned that people might misinterpret the data, they’d rather refer to the CCAC compiled averages and people can draw their inferences from that.”

For many modern-day activists, the argument only further emphasizes the need for transparency. The concern was at the forefront of the 2010 STOP Animal Research protests at the University of British Columbia. Activists filed formal freedom of information requests to UBC for details on animal use in their research programs. In 2011, UBC became the first publicly-funded university to release its research animal statistics. These statistics are released annually online, and include numbers of species and individual animals used in research; the site also lists the types and relative invasiveness of the experiments animals were used in.

Several universities are following suit. Brock University released its animal use statistics on its website in 2015 and students at Queen’s University are urging their institution to do the same by filing similar freedom of information requests.

While these reports continue to disturb many animal-rights advocates like Ash Hulewicz, a fourth-year Environmental Studies student and president of the U of A Vegans and Vegetarians Club, she’s glad that there’s an attempt to be transparent. “A call for transparency is essential for promoting social change, we can’t question a process if we don’t know what the process is,” Hulewicz says. She’s hoping the U of A will similarly step up to break that legacy of invisibility.

“All we know is that animal experiments require annual ethics approval and must follow university regulations, but what are these regulations?” Hulewicz asks. “Why is that information not more transparent? How many animals? What kind of animals? What are they subjected to? Just saying that there are policies in place to mitigate any discomfort an animal might feel tells me nothing about what the animal is actually experiencing.”

For Chloe Taylor, an animal ethicist and associate professor in the U of A’s department of women and gender studies, the lack of transparency is a tactical move by the CCAC to keep students and staff in the dark. She argues keeping institutions from publicly sharing information on animals in research programs makes people less likely to challenge the system.

“I think people are assured that because there’s an ethics requirement, we can just assume that things are being done properly,” Taylor says. “But if everyone could see the animals and what’s happening to them, I think there would be a lot of protests and no university wants that.”

Even though some experiments don’t have the technology to go animal-free, U of A microbiologist Lisa Stein says that most of the time, animals are only used because scientists are entrenched in ancient training.

“We’re teaching students the same methods we were trained on, and they’re the same methods that our supervisors were trained on,” Stein says. “We’re essentially using 1950s knowledge in our highly specialized fields, and because they produce results, we feel like there’s no need to improve. But it’s a stupid reason.”

“We’re teaching students the same methods we were trained on, and they’re the same methods that our supervisors were trained on,” Stein says. “We’re essentially using 1950s knowledge in our highly specialized fields, and because they produce results, we feel like there’s no need to improve. But it’s a stupid reason.”

Even for molecular biology labs that don’t use laboratory animals in their studies, most molecular methods still rely on animal products. Serums needed for growing cells are harvested from the blood of fetal calves, and antibodies used for detecting biological molecules come from immunizing rabbits or mice and collecting their blood.

For Stein, these methods are not only archaic, but also unnecessary. By replacing traditional methods with modern techniques, she was able to make her research laboratory animal-free for “only a marginally higher price.” Stein explained that common serums used in labs can be replaced with synthetic alternatives and that animal antibodies can be swapped out using aptamers, a type of synthetic DNA product that can selectively bind to target molecules just like antibodies.

Likewise, Stein explains that many animal models used to develop treatments also have modern substitutes. The study of phage therapy, treating infections using viruses that kill bacteria, can now be modeled in waxworms instead of mice. Stein feels that many of these animal-free methods aren’t being adopted by most laboratories because of a modern case of scientific elitism, that is, the idea that only scientists have the expertise needed to accurately evaluate animal research.

“People rely on the animal care and use committees to provide checks and balances, but I’ve sat on those before and it’s just people sitting around justifying their ancient training. There’s no incentive for anyone to seek non-animal alternatives or to discontinue animal use,” Stein argues.

The U of A’s Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) is mostly made up of scientists and requires only a single member of the lay public to represent the broader Canadian perspective. Experiment applications are split between four committees: agriculture and livestock, which oversees experiments performed on large animals including pigs and cattle; biological sciences, which includes population studies and field work; and two seperate biomedical committees to evaluate studies performed on small animals including mice and rabbits. ACUC members like Craig Wilkinson say scientists are the most represented demographic because of their knowledge and expertise.

“People are uncomfortable when they think about animals being used in research, it’s human nature, and I’m glad people have that type of compassion,” Wilkinson says. “But people can be assured that those of us in animal research are also animal lovers and we want to make sure that the animals we use are being cared for as well as we possibly can.”

Animals are housed in sterile, climate controlled facilities, and their bedding, water, and food are replaced on strict schedules. The CCAC also mandates that ethics reviews be guided by principles of the three R’s – reduction, replacement, and refinement – to ensure animals are only being used in cases where it’s essential and necessary.

Wilkinson explains that statistical modeling is done to determine the minimum number of animals needed to produce convincing data. Veterinarians intervene and experiments are halted when animals become ill. Biopsies and ultrasounds replace surgeries where possible, and drugs are delivered through food or water to eliminate the discomfort of injections. When the time comes to euthanize the animal, proper anesthetics must be administered first.

“As a vet, sometimes I see people’s pets be in far more discomfort than we would ever allow an animal to be in (during) research,” Wilkinson says. “I think that if people knew how much time, effort, and money went into providing quality care for animals they would be a lot less worried about than what activists say they would.”

Animal rights advocates like Taylor and Stein argue that having scientists regulate scientists is a fatal flaw: Taylor points to a case in 2010 as an example of how research took precedence over ethical concerns. A Canadian research team led by professor Jeffrey Mogil at McGill University videotaped the facial expressions of mice experiencing 14 different pain-inducing procedures to understand how the animal expressed pain. Tails were immersed in hot water, mice were injected with mustard or acetic acid, and nerves were damaged via surgery without anesthesia. When the study was published May 2010 in Nature Methods, a prestigious scientific journal, animal rights advocates complained, calling the work “frivolous,” “unnecessary,” and “unethical.”

The CCAC defended the study, claiming that it provided insight into how mice expressed feelings of pain, and could be useful in assessing mouse welfare. But for Taylor, the fact that this study could have passed an ethics review was both laughable and deeply disappointing.

“These types of experiments have no value or merit to it, it has no impact on improving human lives. Anyone could have seen that. Just because something hasn’t been done before doesn’t mean it’s truly worth doing,” Taylor said. “But of course scientists would defend it — people who volunteer to be on these committees are those who actually have a stake in scientific research and they’d want to protect that. If the public knew more about how animal research was done and could be more involved in the process, things like this would never happen.”

In order for change to take place, Taylor feels that the push has to come from within scientific circles. It’s a sentiment echoed by Stein, who believes that the reason animal experimentation remains so heavily used is due to institutional inertia: the more people there are doing things a certain way, the harder it becomes to drive change.

“It’s a lot easier to keep with the 1950s standards, because it’s hard to change, but it’s possible to modernize biology,” Stein says. “When we turn our attention to efficiency and alternatives, the world changes. It just takes a certain number of people wanting to move in that direction to make it happen.”