Supplied

SuppliedTiago Simões, a recent Biological Sciences PhD graduate, knew Megachirella wachtleri was likely the oldest lizard fossil when he read the 20-year old article detailing its discovery.

However, it took almost 400 days of data collection in 17 countries, and several collaborations all over the world, to demonstrate this.

Simões, who recently published a Nature article detailing his findings, travelled extensively to study numerous fossils and test his hypothesis that Megachirella is the most ancient reptilian ancestor known. The fossils were carefully selected to cover as many reptilian groups as possible. The authors then studied their anatomical characters, such as features of their teeth and vertebrae, to understand the evolution of reptiles.

Megachirella was discovered in the Italian Alps two decades ago and was described as a close ancestor to lizards and snakes, known as squamates. Squamates comprise almost 10,000 currently living species, roughly twice as much as mammals, yet scientists know very little about their evolutionary history.

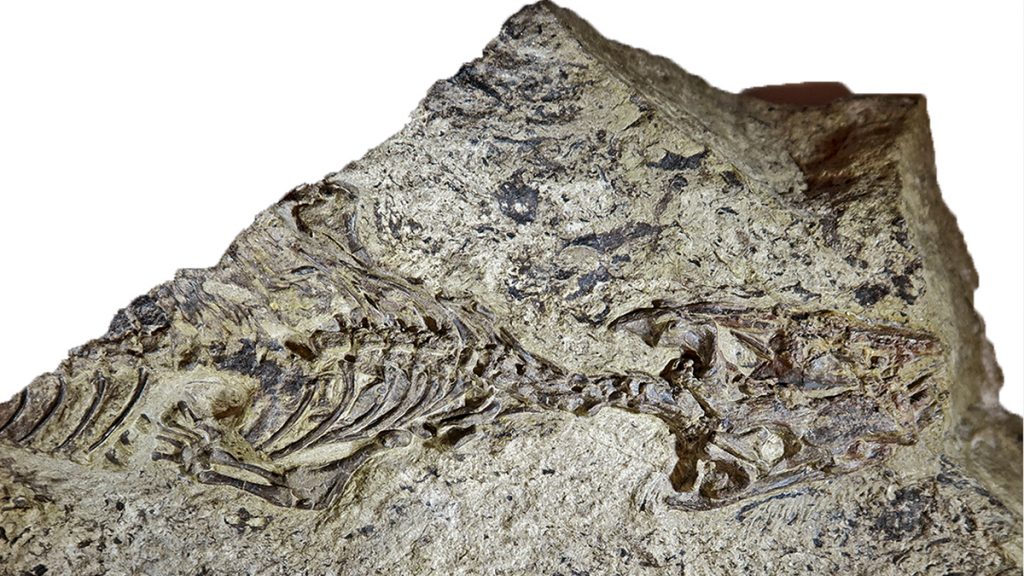

When it came to Megachirella, Simões and the eight other authors of the study looked at the bones in its wrist, skull, arm, and shoulders, with a novel technique in paleontology: high-resolution CT scanning.

CT scans are assembled from X-ray images taken at different angles. X-ray resolution relies on differences in radiation absorption. Bones, which have calcium that absorb large amounts of radiation compared to the surrounding soft tissue largely devoid of calcium, produce a high contrast on medical X-ray images. These specialized CT scans, however, can distinguish the calcium in fossils from the slightly different calcium found in the surrounding rocks.

“[Using this technology,] we saw anatomical characters [in Megachirella] that you only see in lizards and snakes and not in any other group of reptiles either living or extinct,” Simões said. “[Megachirella] is one of those perfect transitional fossils in that it has some of those primitive features but also some features that characterize only lizards and snakes.”

Molecular data, which involves comparing genetic sequences from living species, was also used. The authors then combined the anatomical and molecular data to create the largest assembled reptilian evolutionary tree, which demonstrated Megachirella was the oldest ancestor.

The study also performed an analysis to estimate the time of origin of the ancestral species. What Simões and his team found was that reptilian ancestors existed before the Permian-Triassic extinction, the largest extinction event in history that killed roughly 70 per cent of land species and 90 per cent of aquatic species.

“Most paleontologists and zoologists thought all those major groups of reptiles had originated [after the Permian-Triassic extinction], so instead of the extinction paving the way for the origin of the lineages, it was actually the surviving lineages that eventually led to the large diversity of reptiles we see now,” Simões said.

Although squamate evolutionary studies are rare compared to mammalian studies, Simões believes a better understanding of squamates should be pursued.

“They’re so diverse, ecologically important, [and] they’re also cold-blooded and therefore far more susceptible to climate change, so understanding lizards and snakes is quite valuable to understanding the impact of climate change,” Simões said.