Annea Lockwood helps nature sound off in FAB Gallery exhibit

Danielle Jenson

Danielle JensonWhat: Annea Lockwood, A Sound Map of the Housatonic River

Where: FAB Gallery

When: Now until November 26th

Tickets: Free

Take a look at the great and powerful river which borders our campus to the north, and when you do, consider how crucial The North Saskatchewan is to our city and school. Think about every drop of water, each of its ripples and waves, and the enormous impact it has on the ecosystem around it — one which continues to be created despite our encroachment.

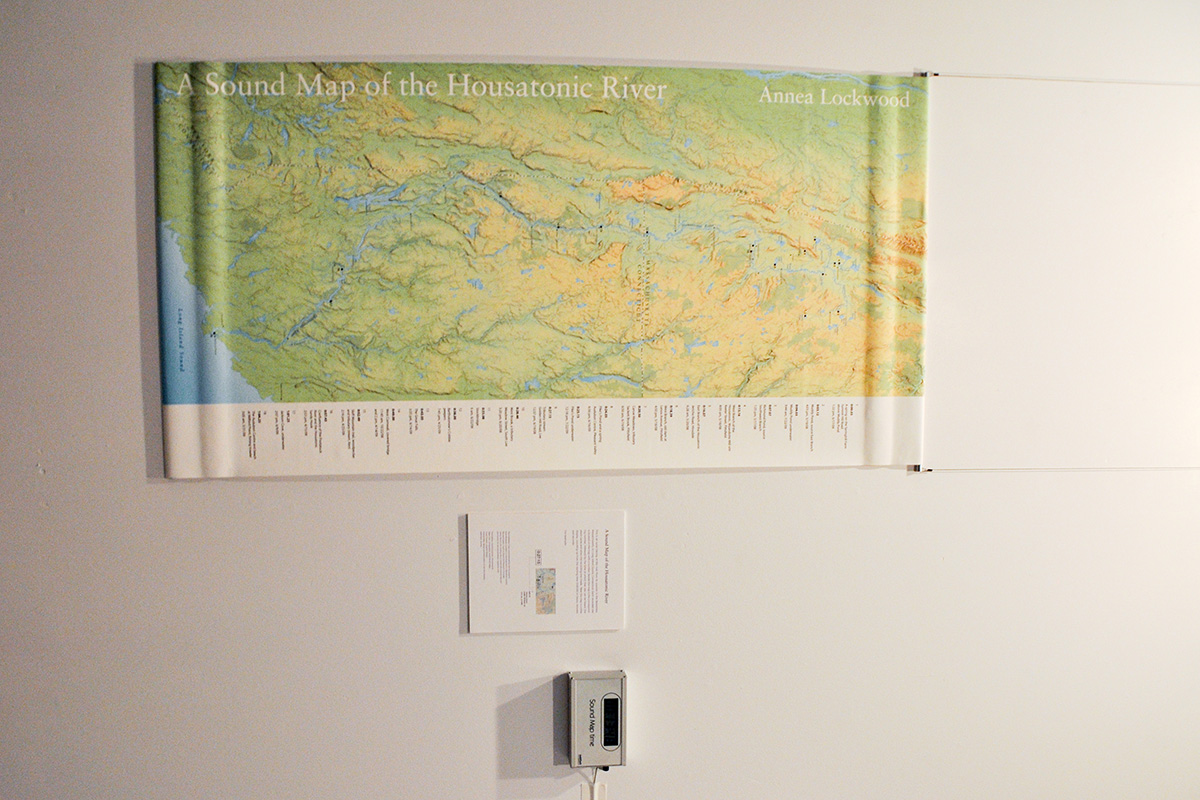

In her ongoing installation, A Sound Map of the Housatonic River, Annea Lockwood — a sound artist and graduate of the Royal College of Music in London, England (Composition 1961) — attempts to capture the details of how a river creates its own ecosystem and dramatically impacts those living around it. Her particular depiction of this phenomenon focuses on the Housatonic River in the Northeastern United States, and is presented as a four-channel sound map, which is available for visiting in the FAB Gallery until November 26.

To experience the artwork, the listener stands at an intersection of sounds between four different speakers, all playing sounds from different perspectives at the same point in a river. This point progresses from the swamps of central western Massachusetts, through Connecticut to its delta, where the river empties into the Long Island Sound.

Lockwood personally collects and compiles the sounds to create an aural tracing of the river that lasts for over an hour. In the same manner that the sound map is a single piece, her art is based on the idea that a river is an entity in and of itself. This idea was concretely demonstrated in a historic legal decision.

In 2012, the Whanganui River in New Zealand — Lockwood’s motherland — was officially granted legal personhood. This action “give(s) (the river) rights and interests,” explains Lockwood, providing legal status similar to that obtained when starting a company.

This river has a strong association with the Iwi, the Maori community who have had strong ties to it long before European settlement.

“The proposition that a river has personhood and therefore rights, to my mind, is a wonderful step forward,” Lockwood says. “Especially, the right to be whole.”

In displaying the whole of the river, Lockwood wants to leave the listener with more than a mere description. Her work attempts instead to respect and realize the Housatonic for all the different pieces that come together to create the river.

“I want to build on that sensation that occurs when a listener feels immersed in sound,” Lockwood says. “Sound is constantly moving through our bodies, vibrating cavities and liquids, and affecting our blood pressure and muscle reactions and so on. It has profound effects on our bodies, of which we’re not normally aware.”

In this way, Lockwood notes, when a river changes, it affects every aspect of its ecosystem in some way. While rivers don’t appear to change all that often, Lockwood explains how quickly a river can evolve. While compiling sounds for her Housatonic River sound map, she was recording near a delta of the Pootatuck river, a tributary of the Housatonic, when she noticed a sudden change in her recording.

“I didn’t know the Pootatuck had a little dam upriver which released water every so often, so I was recording (the rivers’) confluence, which made a really delicious sort of sound, and little by little, the sound got quieter and quieter and quieter as I was recording it,” Lockwood recounts. “I was there no more than 10 minutes, and I noticed that my mic was just about underwater. So, even in that 10 minutes, that sound changed.”

It’s because of these changes Lockwood can be critical of her work as an art form, without necessarily painting a picture of the river with such a broad brush. She views herself instead as an admiring observer that wants to display the beauty of water to the world, so that we may preserve what the Earth has given us.

“I’m hoping that whatever experience one has while listening can transfer into those broader concerns and into action on behalf of the environment,” she says. “We can develop a caring for the phenomenon that creates those sound fields… and from that caring, we can act.”