Christina Varvis

Christina VarvisOver the past 50 years, the University of Alberta’s Department of Anthropology, like the cultures it studies, has adapted to the transformations and upheavals in Canadian society.

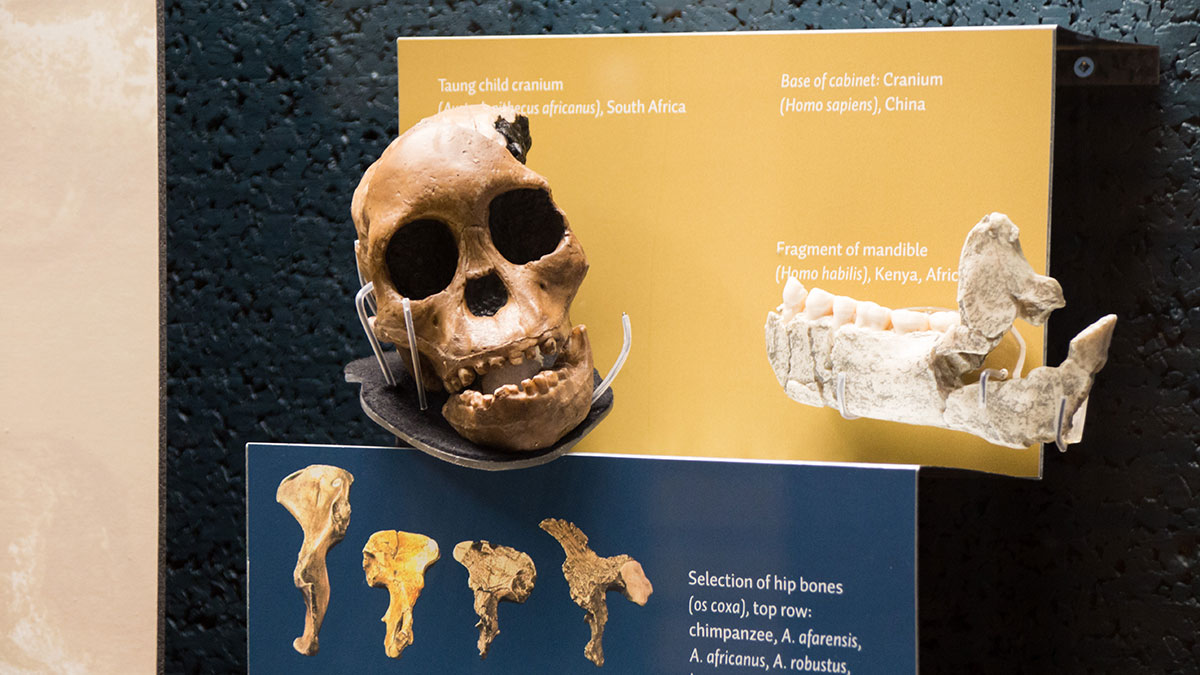

The Department of Anthropology celebrated its 50th anniversary on Jan.8, unveiling a new display on the 13th floor of the Tory building, which commemorates the achievements of U of A staff and alumni in the field of anthropology. 2016 is being heralded as a year for the U of A to reflect not only on the success of the department since its inception in 1966, but on the growth of the study of anthropology within an increasingly diverse Canada.

But for Pamela Willoughby, the Chair of the Department of Anthropology and a U of A alumnus, the anniversary is first and foremost a celebration of the department’s “divorce” from sociology.

“I’m sure it was an amicable split,” she said with a laugh.

Anthropology was introduced to the U of A in the 1950s within the Department of Philosophy and Psychology before moving into the Department of Sociology. Despite their common history, Willoughby said she believes sociology and anthropology share more differences than similarities, and the separation of the two departments has helped anthropology at the U of A “specialize and legitimize itself.”

“Sociology is the study (of) the social behavior of people like us, whereas anthropology is (the) study of people who are very different than us,” Willoughby said. “Having a (department) that says all human societies have value and all of us should be interested in understanding the differences between human societies … is very important.”

The Department of Anthropology developed during a revolutionary period for Canada’s demographic. According to Willoughby, one of the biggest changes in her field came with the adoption of the Multiculturalism Act in 1988, which promoted ethnocultural diversity within Canada. In 1966, less than 3 per cent of Canada’s population was a visible minority – by 2011, this number had grown to 21 per cent, and over 200 ethnic origins were reported in that year’s federal census.

“Now, the world is coming to us,” Willoughby said. “As people from other cultures move here, there is a question of how they will accommodate our society, and anthropology can help foster a common understanding of different cultures and our own.”

Willoughby said anthropology at the U of A is “smaller than it used to be,” partly because disciplines like native studies have also branched out and become their own faculties. For Willoughby, this is not a sign of regression, but an indication of a positive societal shift towards equality and reconciliation.

“(Anthropologists) were once the people who said, ‘We need to address these people’s issues and concerns,’ but now those people can speak for themselves,” Willoughby said.

“While we once had the monopoly on Indigenous studies … anthropology is now allowing for healing.”

Emily Parsons is in a comparable position to the one Willoughby found herself in 42 years ago when she first came to the U of A. Parsons is currently completing an honours degree, and hopes to focus her studies on gender when she pursues her master’s degree in anthropology next year. She, too, noted the effects of progressive social change over the past 50 years on the study of anthropology in Canada.

“Anthropology … used to be very male-dominated, and it used to have a much different attitude,” Parsons said. “Now I go into all of my classes, and it’s all women.”

“It’s not a boy’s club anymore. It’s not isolating. We’re getting different perspectives now, and it’s really, really important.”