supplied

suppliedUniversity of Alberta computing scientist Greg Kondrak and graduate student Bradley Hauer believe the 600-year-old Voynich manuscript may have originally been written in Hebrew.

Produced in the 15th century and discovered in an Italian monastery, the Voynich manuscript has defied all attempts at decryption. Even British cryptographers at Bletchley Park, famous for deciphering the Nazi’s enigma code, failed to translate the text.

“The text has not been deciphered until now,” Kondrak said. “Even though many people have tried and many people have claimed to have deciphered it.”

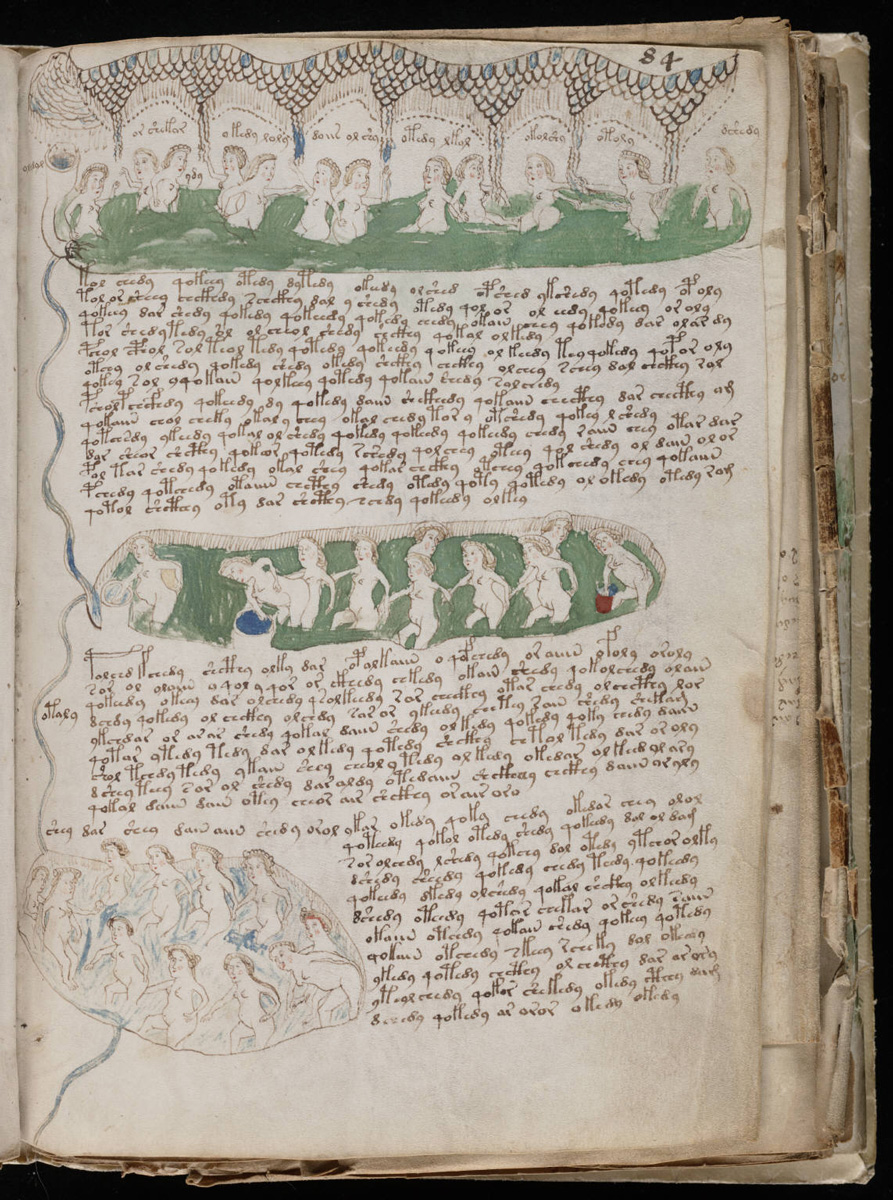

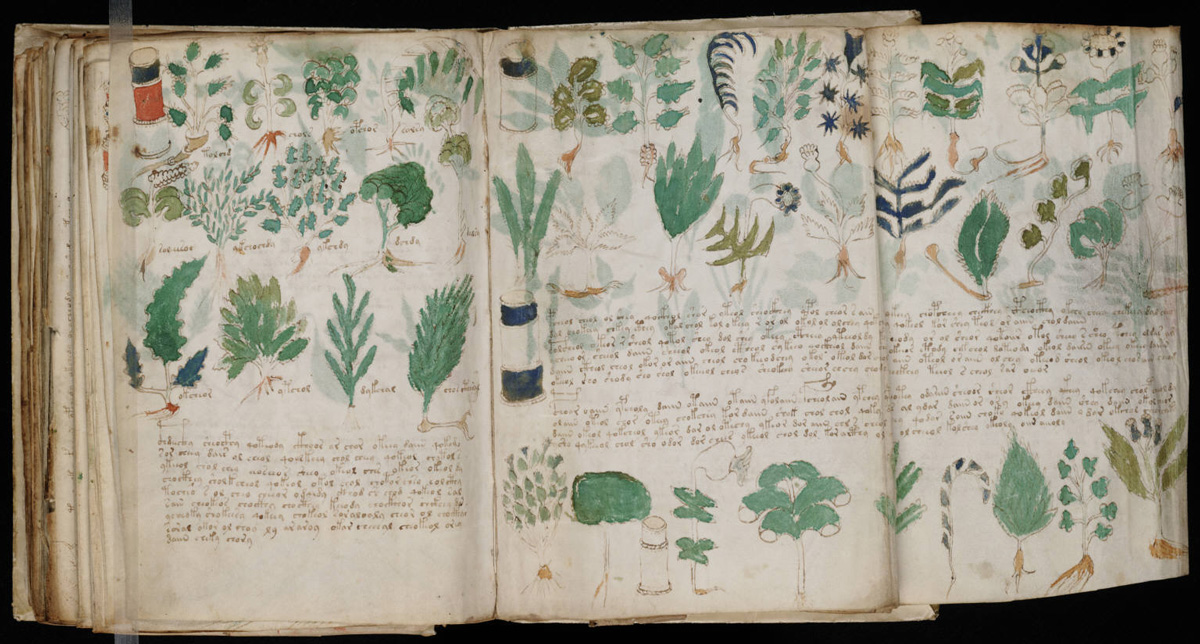

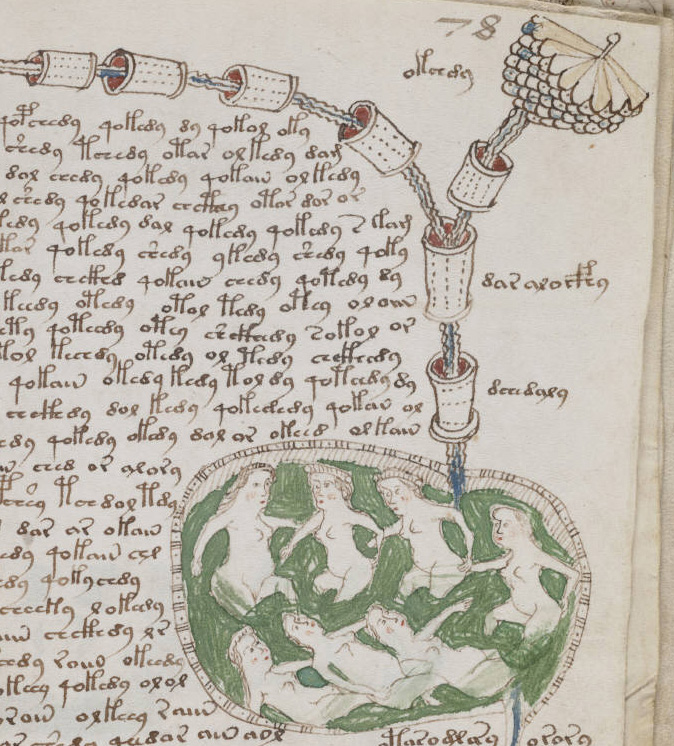

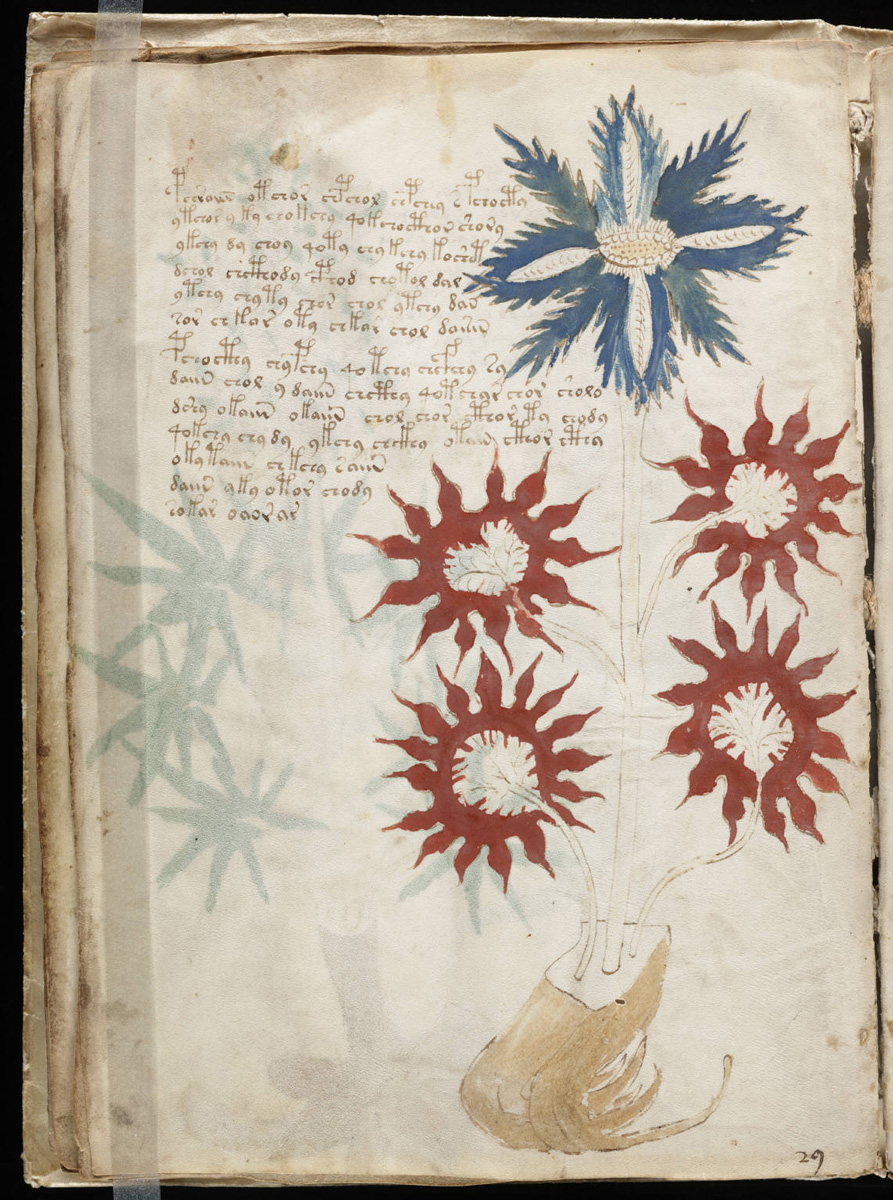

The document is written in an unknown script and language, on pages decorated with illustrations of strange plants and naked women in baths. The writing utilizes a unique alphabet, not found in any other ancient texts. These symbols are thought to have substituted original letters to conceal the work’s intended meaning.

To unravel its mysteries, Kondrak and Hauer first set out to identify the manuscript’s language.

Kondrak explained that languages construct words and sentences in unique ways. Letters and words are repeated in specific frequencies and arrangements. Even without understanding which letter each symbol represents, the language in which encrypted scripts are written can be identified through statistical patterns.

Kondrak and Hauer trained a computer algorithm to recognize 380 languages using different versions of the United Nations declaration of human rights. When the program was applied to the Voynich manuscript, the algorithm was 97 per cent confident that the writing is in Hebrew.

To translate the writing, the program was taught every word in the Hebrew bible. But decoding the text has proven more challenging than identifying the language. Kondrak explained that the Hebrew alphabet is an abjad, a writing system where vowels are removed, which makes decryption difficult.

“There’s a lot of ambiguity, you can put vowels in wherever you want to make it into a real word,” Kondrak said. “But then that means it’s only one interpretation of many, it’s possible that your guess might be correct, but you can never be sure.”

Many historians who do not believe the manuscript to be in Hebrew have cited this as a fatal flaw in Kondrak’s work. However, Kondrak continues to stand by the science.

“If someone in the future completely deciphers the manuscript and they can confirm that it’s indeed Hebrew, I’d be very happy, but at this point it’s an educated guess,” Kondrak said. “The duty of the scientist is to come up with hypotheses and provide evidence to support (that) as much as (they) can.”

With the help of a Hebrew speaker, Kondrak translated the first line of the manuscript as, “She made recommendations to the priest, man of the house, and me, and people.”

The team is now awaiting a historian well-versed in Hebrew to translate the rest.

“It’s important that we do it,” Kondrak said. “We want to understand what our ancestor’s lives (may have been) like, it’s part of our human history.”