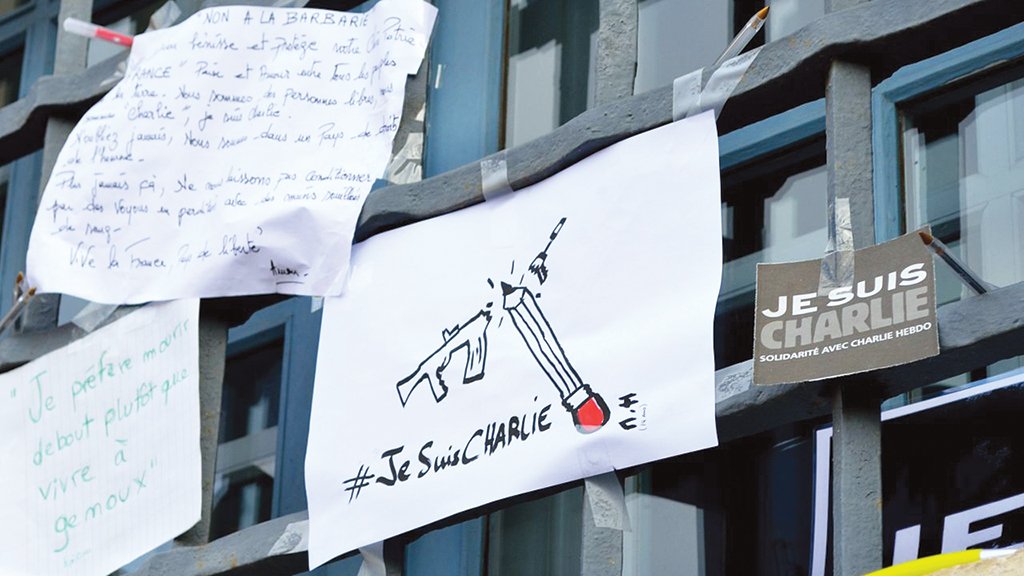

Questioning the journalistic approach to free speech in the wake of Charlie Hebdo shooting

Supplied - Gyrostat (Wikimedia,-CC-BY-SA-4.0)

Supplied - Gyrostat (Wikimedia,-CC-BY-SA-4.0)As an aspiring journalist, I hope to give a voice to the voiceless, tell meaningful stories and keep citizens informed. To me, freedom of speech is the core value of journalism. However, the attacks at Charlie Hebdo have placed me in a rather muddled position.

Without a doubt, a tragedy has taken place and nobody’s lives should have been sacrificed. Immense perseverance and strength was needed to continue publishing a “survivor issue” despite what happened. The magazine’s determination to not bow down to terrorism is something to take pride in. I remember feeling proud of the publication when I heard new issues were flying off the stands around the world and the demand for it continues to increase. This shows the world stands by Parisians in their fight not to let terrorists deter free speech.

But upon watching some interviews with journalists around the world, the issues brought up made me look at this tragedy in an altered way. It began when media outlets such as CNN, ABC, The Daily Telegraph and The New York Times made a decision not to display the new cover to their audience. I asked myself why these major companies refused to join a symbolic movement fighting for the freedom that forms the very foundation of their work.

Then I thought, perhaps these publications stand by the belief of freedom of speech not including mockery or shaming of anyone’s religion. Religious tolerance should be something upheld in all societies. Everyone deserves the right to free speech, but that shouldn’t include hateful remarks or depictions. For example, being able to have freedom of speech in Canada doesn’t mean anyone can say whatever they want. As ironic as it sounds, freedom comes with limitations.

Charlie Hebdo, as a satirical magazine, claims their content exists for the purpose of humour. Shows like The Colbert Report and The Daily Show are satirical in nature, and people enjoy watching them for entertainment. A lot of people don’t always share the same sense of humour, but one’s race or religion shouldn’t be scorned under the justification that it’s just for humour. The line that defines mockery and freedom of speech remains ambiguous and can be debated from many points of views.

Naturally everyone thinks differently, and newspapers and magazines often have to report stories of multiple attitudes of life. The matters they report on can’t guarantee it won’t offend anyone’s way of thought. For example, journalists reporting on gun control laws may anger people who own guns. But while publications retain the right to report on significant issues, they also have a responsibility to uphold a reputation of religious tolerance.

The co-founder of Charlie Hebdo, Henri Roussel, questioned “what made him feel the need to drag the team into overdoing it,” with ‘him’ referring to editor Stéphane Charbonnier and his decision to depict the Mohammed character in 2011 (The Telegraph). Roussel recalled the times where the magazine continued to stir up controversy even after attacks, and Charbonnier’s stubbornness despite his advice.

Reading Roussel’s harsh critique had its difficulties, especially after so many innocent lives were sacrificed. However, his remarks solidify the issue of free speech vs. ridicule. It’s necessary for all journalists, in the wake of what happened in Paris, to question whether they’re at times going too far with satirical criticism or whether it’s more important to fight back with Je Suis Charlie.