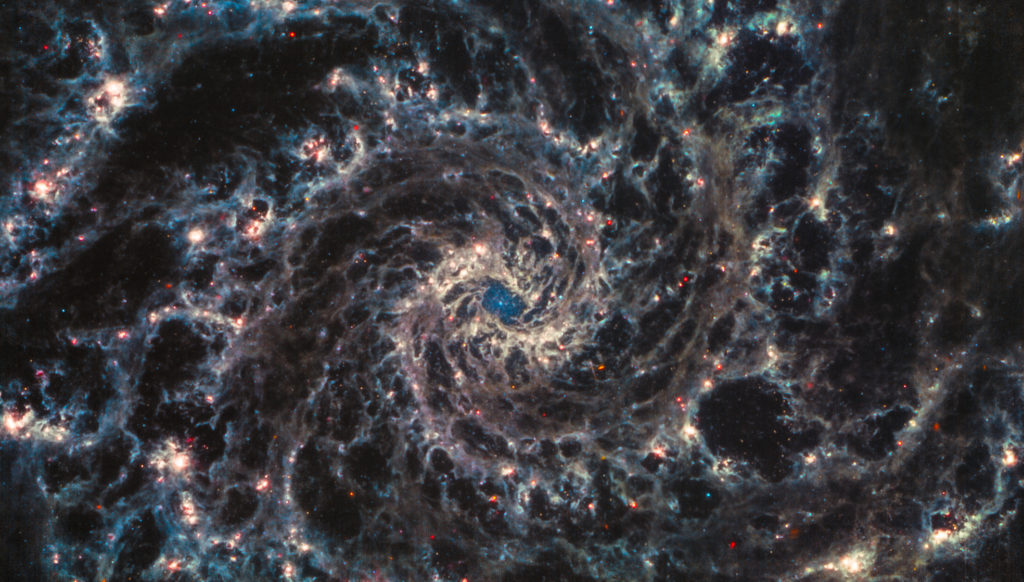

NASA / ESA / CSA / Judy Schmidt

NASA / ESA / CSA / Judy SchmidtA research team led by the University of Alberta has made new discoveries about the formation of spiral galaxies and how they evolve over time, from the first-ever images that capture the early stages of star formation.

The discovery was made by Hamid Hassani, a PhD student in the department of physics and and lead author of the study, and co-author Erik Rosolowsky, a professor in the department of physics. Hassani and Rosolowsky discovered young stars that were erupting instantaneously when examining the infrared light emitted from interstellar dust clouds.

“Infrared light — which we can’t see with our eyes — has lower energy than the light that we actually see,” Rosolowsky explained. “The reason why the new space telescope is so amazing is because it’s giving us this first, really high-resolution, beautiful view of the infrared light.”

The images were taken by the James Webb Space Telescope, which has mid-infrared technology that allows it to capture images of stars that would otherwise be invisible due to stellar pollution.

Even though infrared light can’t be seen, it gives off infrared radiation. When light passes through gas clouds, there is also dust mixed in, creating stellar pollution that blocks the light from young stars.

However, the stars heat up the dust and create infrared light, which can be captured by the James Webb Space Telescope.

“Otherwise, these stars would be invisible — they’d be cloaked behind the gas that’s giving birth to them. So we can actually see the first stages of star formation because we have this great new view of infrared light,” Rosolowsky said.

The study explores how galaxies are evolving, and why a galaxy can last as long as it can. According to Rosolowsky, one reason could be that when stars are being born, the light that touches their surroundings “essentially heats up the gas, stopping the galaxy from eating all of its fuel really quickly.”

“The idea that we’re trying to study is whether that is effective, or whether that’s actually the reason why galaxies last a long time.”

By using data from the James Webb Space Telescope, Rosolowsky discovered the youngest stars that can be found, as they were right on the cusp of star formation. This finding showed how close young stars are to their surrounding gas, and how much light is being poured out into that gas.

“Our conclusion was that they actually put out a lot of light,” Rosolowsky said. “Star formation is important because it literally builds galaxies, but it also is important because it kind of regulates itself.”

The research team plans to continue using the James Webb Space Telescope to research different types of galaxies, and observing different kinds of light.

As younger stars also give off ultraviolet light, Hassani and Rosolowsky are planning to study it along with radiation, to continue “gathering a more complete picture by all the different colours of light that tell us about the galaxy,” Rosolowsky said.

“In Canada, we have access to using a different satellite, and we’re really excited about studying the ultraviolet radiation and light, and comparing that to what we’re seeing in the infrared.”

Rosolowsky added that the discoveries being made are changing what is taught in the classroom.

“Not just our discoveries, but a lot of the new insights are transforming what we’re teaching here, so I think that’s really exciting.”