Film Review: ‘Meadowlarks’

U of A professor Tasha Hubbard's new film demands that we confront and learn about a history that wants to be forgotten.

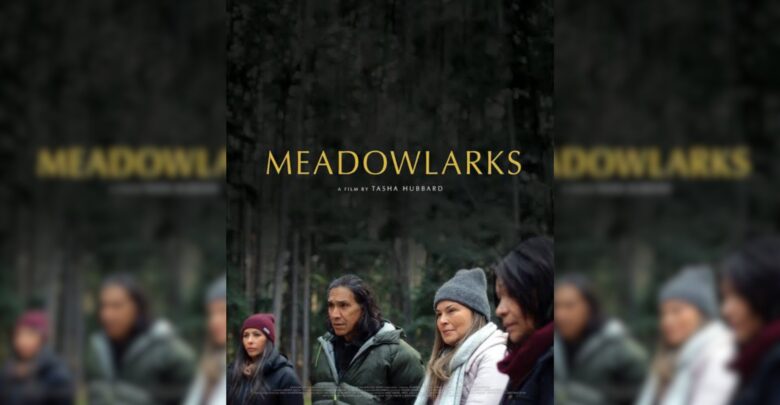

Supplied

SuppliedUniversity of Alberta professor and filmmaker, Tasha Hubbard’s new film, Meadowlarks, is based on her 2017 documentary, Birth of a Family. The documentary follows four siblings coming together after being victims of the Sixties Scoop. Meadowlarks is a drama, following the same story.

The Sixties Scoop refers to the 1960’s forced removal of thousands of Indigenous children from their families and places of birth across Canada and the United States. The children were then adopted into non-Indigenous homes.

Over one weekend in Banff, four estranged siblings reconnect with one another. They share their stories and discover the truths that were stolen from them. Over the four days, the film follows the siblings’ painful journey to regaining who they are as they confront and overcome the fear that they never fully will.

I have to admire the dynamic storytelling that director, Hubbard, and screenwriter, Emil Sher, weave into this film. We gain insight into the lives of each of the siblings in the years that they have been separated. Even George, the sibling that refused to come to the reunion, has a complex storyline like everyone else. With this, the film presents a multi-dimensional insight into the lives of Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Hubbard highlights Indigenous voices and the complexity of Indigenous stories and characters that are often portrayed as one-dimensional in Canadian film and television.

Each siblings’ story delivers powerful insight into the alienation that occurs when you have your identity defined by someone else. And that alienation is portrayed in many ways. Notably, how they felt within the foster care system, and their disconnect at the beginning of the film. They also confront alienation from their culture and language. They fear not seeing themselves in their own people, and the sinking feeling that they have no heritage to pass down.

One of the most striking portraits of alienation is a moment of realization from one of the characters. Gwen, one of the siblings, at one point admits to feeling powerless to change how other people, particularly the Canadian government, perceive her. Similarly, the same thing that happened to their mother. With this, Hubbard does well to show us how cycles of discrimination further a generational detachment.

Near the end of the film the four siblings have a sit down with two Indigenous Elders. This scene stands as a reminder that there exists a community that never forgot them. And, how that community is willing to support them on their path to putting themselves back together.

Something I think plays well into this theme is the way that the storytelling and cinematography work together as they follow the siblings on their journey of self-discovery. James Klopoko, the film’s cinematographer, carefully portrays the beautiful scenery of Banff. It represents freedom and possibility, which contrasts the fear and uncertainty the siblings have when they first meet. The landscape is almost teasing the siblings — reminding them of the beauty of the home they never really knew. Klopoko skillfully plays with the cool blue lens at the beginning of the film that highlights that initial disconnection and alienation. Then, he uses warm hues that fill the screen at the film’s concluding scene as characters are portrayed together.

The film does not fully answer all of the questions that the audience has. But I believe that this is a powerful tool as it demands further research from the audience. It demands that we confront and learn about a history that some want to be forgotten.

I definitely recommend giving the film a watch. Meadowlarks does well to confront patterns of alienation and powerfully uses Indigenous voices to tell Indigenous stories.