‘Connections’ exhibit showcases talents of U of A scientists and artists

The Royal Alberta Museum exhibition is a collaboration between the university's Neuroscience and Mental Health Institute and the faculty of arts.

Supplied

SuppliedArt and science are usually seen as two distinct areas of study. Ask anyone, they would probably confidently tell you whether they’re more of a science or art person. But what happens when the two come together and work hand-in-hand?

Two University of Alberta faculty members answered this question when they conceived of the Connections project. In 2020, Simonetta Sipione, a pharmacology professor, and Marilène Oliver, a fine arts professor, developed an online gallery that showcased an array of neuroscience images. The intention was to portray the delicate intricacies and connections between the brain, mental health, neurological diseases, and the neurological healing process. The gallery was then turned into an exhibition at the McMullen Gallery in the U of A hospital. Now, Connections is the latest temporary exhibit at the Royal Alberta Museum (RAM).

Connections is a collaboration between the Neuroscience and Mental Health Institute (NMHI) and the faculty of arts at the U of A. It strives to highlight the physical connections in our brains, and how they interact in relation to mental health, disease, and recovery. The exhibit emphasizes the importance of art as a force of healing, and how science and art function in relation to each other. I sat down with two Connections contributors to discuss their involvement and how the exhibit has impacted them. Tamara Deedman, an artist and assistant lecturer in the department of art and design, and Brian Marriott, a neuroscience PhD student, both contributed works to the exhibit.

“My work … [has] always kind of been headed by grief,” Deedman says

Oliver invited Deedman to create pieces for Connections because of the strong thematic parallels between her work and the vision for the exhibit.

“My work … [has] always kind of been headed by grief. Specifically grief within the lens of … loss of innocence due to trauma but … also like, loss of a person,” Deedman explained.

Deedman is primarily a printmaker, and she explained the significance of making her mark through chemistry instead of paints or charcoal.

“The act of printmaking is about the multiple. You get to make and make … and you can kind of change it as you go.”

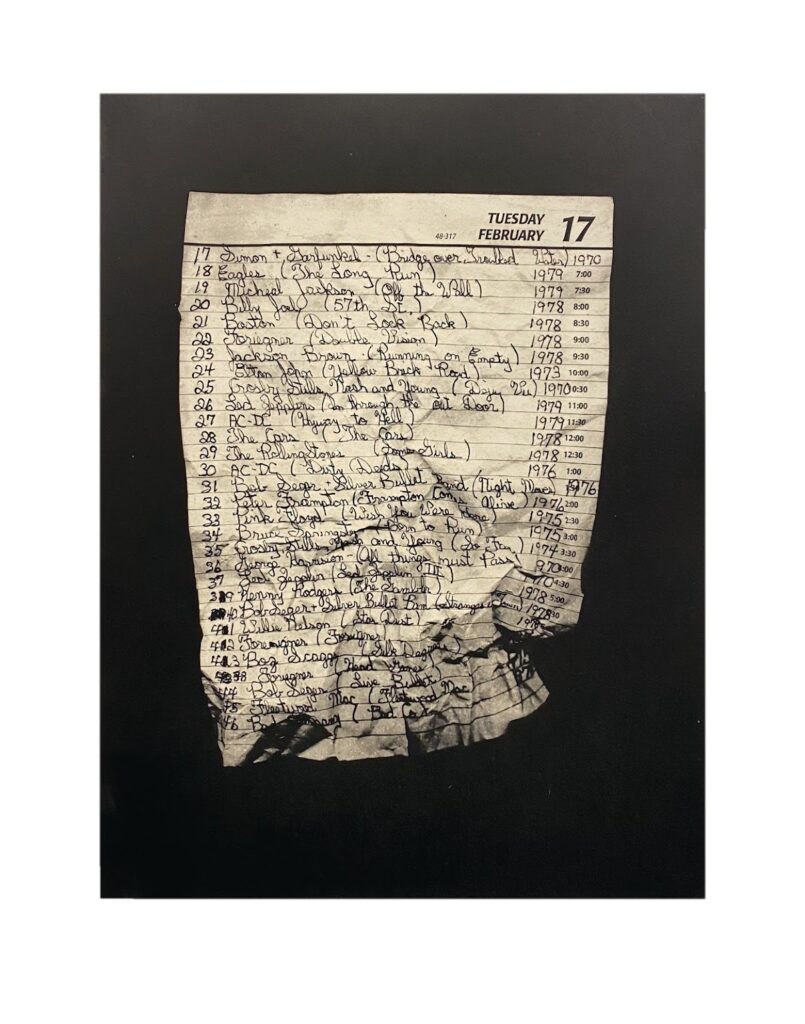

Printmaking also connects her to her late father, the subject of her pieces in the exhibit. Deedman created five prints of a list of her father’s CD collection from his archives. In each print, the list gets increasingly more crumpled, and in the last one, the print is bombarded with saturated colour. She explained that creating prints is a similar activity to collecting. In making her work, Deedman is “enacting the same coping mechanisms as he was.”

Deedman said she was “very honoured to be asked to be part of the exhibit.” She explained the “tumultuous” nature of her relationship with her father, and how she wasn’t able to give him a funeral, as he died during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“This … body of work … feels like a collaboration with him and … the funeral I can never give him. It was a really big bookend for the work … which honours my father,” she said.

“The collaboration is … incredible. Because it’s an opportunity for us scientists to take a different angle on things,” Marriott says

Marriott works on foundational neuroscience research that looks at “different parts of the brain and trying to figure out what they do.” He is specifically interested in the claustrum, a region of the brain that has an unknown function. Marriott uses microscopes and photography to observe different regions of the brain.

Marriott has three images in the exhibit. One portrays how “two different, but very closely related, parts of the brain connect to other parts of the brain.” Marriott describes the photo as “striking” because it displays how many small connections and pathways exist in the human brain.

The second is an image of the enigmatic claustrum. Marriott explained that the claustrum has about 1,000 specific cells that connect to “so many other regions of the brain, and we don’t know what those connections are actually doing.”

Marriott’s third image shows his hands holding a model of an astrocyte. “An astrocyte,” he explained, “is more of a supporting cell in the brain.” It provides nutrients and supports to the neurons that surround them. Each image emphasizes an important connection in the brain, and communicates the importance of connections in the lives of people.

Marriott expressed that the Connections exhibit is important for a couple of reasons. Firstly, it allows for the public to bear witness to the work and research scientists do that is usually inaccessible. It allows for anyone to break the physical barrier of the cranium by seeing these brain images.

“The collaboration [between science and art] is … incredible. It’s an opportunity for us scientists to take a different angle on things,” Marriott said.

Connections explores both the emotional and physical realities of the human brain. It marks the importance of both science and art, and the power that lies in their relationship. The Connections exhibit is at the RAM until June 22.