Supplied

SuppliedRussell Cobb’s recently released book, Ghosts of Crook County: An Oil Fortune, a Phantom Child, and the Fight for Indigenous Land, details a true story of a massively wealthy oil entrepreneur trying to buy land owned by a boy named Tommy Atkins. Atkins, despite having family and other people claim to know him, was never found and may not have even existed.

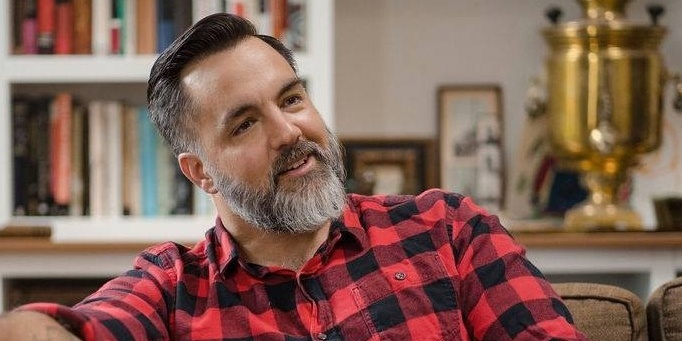

Cobb is the co-ordinator of the media studies program at the University of Alberta and an associate professor in the department of modern languages and cultural studies (MLCS).

Hailing from Tulsa, Oklahoma, Cobb cited the Tulsa Race Massacre as his “initial inspiration” into “what is left out of the official recording of a narrative of a place.” The Tulsa Race Massacre, which occurred in 1921, resulted in the deaths of between 50 and 300 people and the destruction of Oklahoma’s second-largest Black community.

Growing up in Tulsa, Cobb said that he noticed hints to a hidden past, but didn’t learn what that history was until later on. He recounted buildings that were purposely designed to look melted or stairs that quite literally lead to nowhere, all done in an effort to hide what had happened not even a century before.

“Until maybe 20 years ago, most of this was not recognized or discussed. White Tulsa just wanted it to go away, but Black Tulsa also hid part of it because they were afraid it could happen again,” Cobb said.

“There was an incredible backstory that … nobody had ever talked about,” Cobb says

His new book dives into the same territory — hidden and unwritten history. He stumbled upon the story naturally when he was selling a property in Oklahoma.

While selling his mother’s house in Oklahoma, his realtor told him that at one point the property had belonged to an Indigenous person, but that it was unclear how the property had transferred from them to the next owner.

Cobb looked into the history of the house and uncovered a story involving oil companies buying up land. This led to the story of Tommy Atkins and the ways in which oil companies would immorally acquire land from Indigenous peoples in Oklahoma.

“I found [that] there was an incredible backstory that … nobody had ever talked about,” Cobb said.

Almost exactly a year before Cobb’s book was released, Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon came out. The film is based on David Grann’s book of the same title, detailing similar theft of land from Indigenous peoples in Oklahoma not far from Tulsa.

“It definitely inspired me to keep pushing. Osage County is just north of Tulsa. If this is happening up there in rural Osage County … it is entirely possible that something like that [was] also happening in Tulsa, and no one is talking about it,” he said.

”You don’t know what’s not there,” Cobb says

Angie Debo was an Oklahoma historian who had looked into the same story as Cobb earlier on, but after receiving death threats, she did not continue her work. Cobb noted how he was able to “[take] up the parts of the work that she started and wasn’t able to finish,” and add more to the story that she had missed.

Cobb said that while her work was great, “she had a lot of blind spots.” Many of Oklahoma’s Indigenous population were also Black, which was left unwritten from history, according to Cobb.

Their part in everything from the “frontier war, natural resource exploitation, cowboys to country and western music” was unrecorded. Cobb made sure to have this history unhidden.

On his research process and choosing where to look, Cobb quoted Robert Caro, saying “my advice is to turn over every page.”

“You don’t know what’s not there. How are you supposed to know that in this one archive, there’s a record of a murder that no one ever discovered. Turning over every page in an archive is very tedious, not every page is exciting,” he said.

Cobb’s book holds a strong connection to Alberta. This is evident in Alberta’s own history of residential schools, to the more recent issue surrounding the Keystone XL pipeline negatively impacting Indigenous land.

“Those connections have been there forever, and they’re only getting more and more globalized,” Cobb said.