U of A performance of Eugène Ionesco’s play ‘Rhinoceros’ revels in absurdity

Studio Theatre’s latest show displays the tenets of early postmodern theatre.

Supplied: Brianne Jang

Supplied: Brianne Jang This winter Studio Theatre took on a challenging production about fascism, rhinos, and relationships.

From February 9-18, the Studio Theatre at the University of Alberta showcased the graduating Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA) acting class in Rhinoceros. This performance, directed by Jake Planinc, features Martin Chimp’s translation of Eugène Ionesco’s original French play for English-speaking audiences.

The show was just as absurd as one would imagine given its title, and very much felt like a production that was meant to be performed in French with some awkward phrases in the translation. It is a difficult production to pull off, due to it’s fast-pace and experimental style.

Studio Theatre puts on four shows a year at the Timms Centre for the Arts. This group provides hands-on experience for students in the BFA program and introduces the soon-to-be-graduates to Edmonton’s larger theatre community. Rhinoceros is the third performance in the 2022-23 season, following Weasel by Beth Graham and Ubu Roi by Alfred Jarry.

Twentieth century playwright Ionesco is considered the unofficial king of absurdity, and his 1959 play Rhinoceros is certainly no exception.

The play opens in the main square of a small French town. A dishevelled man, Berenger (played by Will Gosse) rushes to meet his friend, the well-groomed Jean (played by Patrick Lynn). As the two begin arguing about Berenger’s drinking problem and general incompetence, they are interrupted by an off-stage rhinoceros, indicated by trumpet calls played over a loudspeaker, barreling through the town.

As the plot develops, it is revealed that townspeople are catching a disease called “rhinoceritis,” which causes them to turn into rhinoceroses. After his coworker-turned-lover Daisy (played by Amy Bazin) leaves him to become a rhinoceros, Berenger is the last man left standing, held up in his apartment with a gun and his slipping grasp of reality.

The fictional disease has often been read as an allegory for the rise of fascism and Nazism prior to and during the Second World War. Ionesco uses humour throughout the production to both lighten the tone and provide an indication of how characters use comedy to rationalize the absurd events going on around them.

Unfortunately, this critique is intertwined with a problematic narrative about regression and animality that reflects colonial ideologies. It is impossible to view the production in a contemporary setting as a purely political critique, as it relies heavily on stereotypical binaries that generalize all non-European cultures through references to the wildness and destructive nature of the rhinos. The jokes about the confusion of African and Asian rhinos were dated and should not be performed in current iterations of the play.

Much of the dialogue swaps between several sets of characters having parallel conversations. These conversations were difficult to follow, as the actors jumped in sporadically overtop of each other.

However, the interplay between Jean and Berenger in the opening scenes was quite effective — a refreshing interjection of the realistic into this ridiculous plot. Jean’s transformation after the intermission was portrayed impeccably by Lynn, or at least as accurate as I could imagine the metamorphosis into a rhinoceros to be.

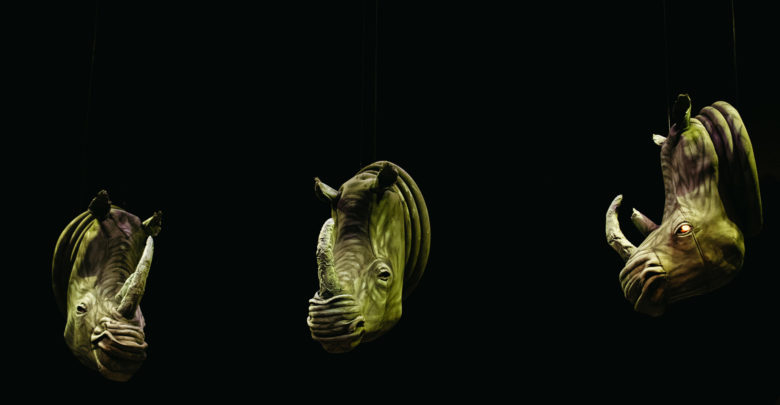

As the cast became more rhinoceros than human, they wore disturbing headpieces and stomped from the aisles down to the front of the stage in a truly unsettling manner. A large rhinoceros cutout sat behind the actors and the set for the duration of the performance. Initially, it was hidden so that the audience couldn’t quite tell what it depicted until it was slowly revealed as the disease simultaneously overtook the town and the coherence of the narrative. We all knew what was coming, but that did not make us any less confused by the end of the play.

The next and final production by Studio Theatre for the academic year follows similar themes of hysteria, but through a narrative inspired by true events. The Devils by John Whiting will be playing at the Timms Centre for the Arts from April 5-15 with reduced pricing for students.