Q&A: MFA Artist Alissa Rossi on ‘The View From Where’

U of A artist speaks to the intertwined fates of local boreal forest ecology and technology, while inviting viewers to reflect on how we view ourselves as dominant entities within nature, through her printmaking exhibition.

Supplied: April Dean

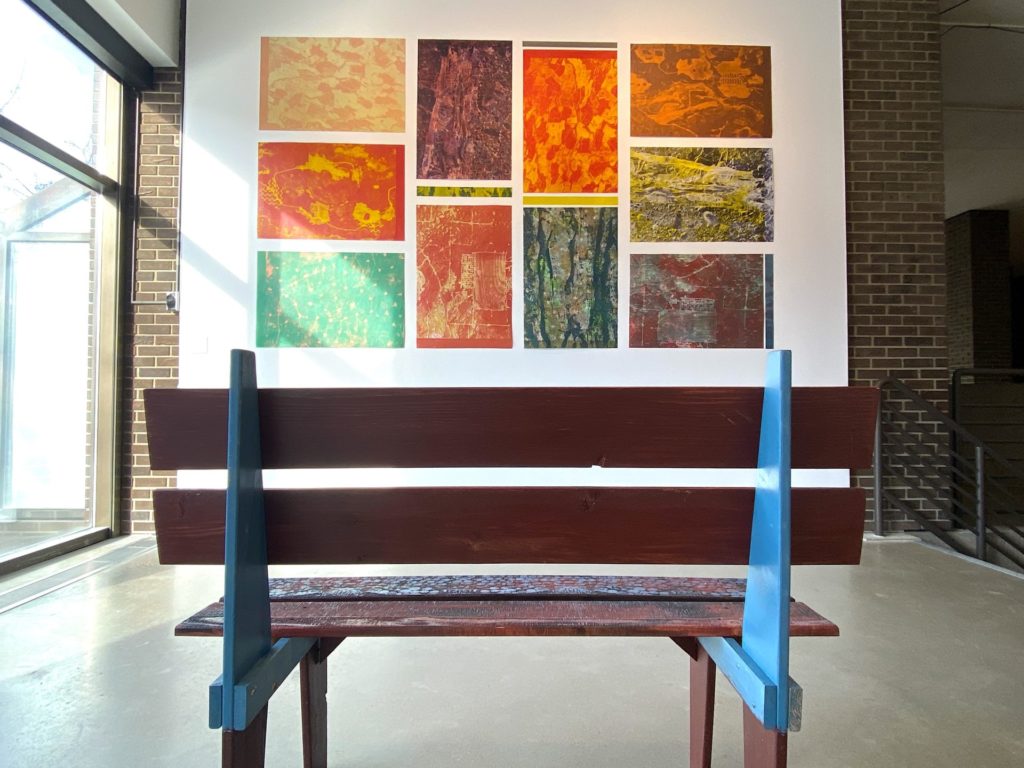

Supplied: April DeanMFA Printmaking artist Alissa Rossi presented her exhibition, The View From Where in the Fine Arts Building Gallery from October 11 to November 5.

Her exhibit presents a new way of looking at the ecological world, by allowing technology to play a leading role in guiding the creative process. These prints encourage observers to explore how the ongoing climate crisis has manifested itself on a local level with imagery from the boreal forests of British Columbia and Alberta.

The Gateway interviewed Rossi about her exhibition, highlighting larger prints showcased in the gallery, and how print-making helps communicate the deeper themes of her work.

Responses have been edited for brevity and clarity.

The Gateway: How does printmaking shape The View From Where?

Alissa: The work that’s up in The View From Where is interesting because I, and I would say this is partly because of the pandemic, went back to doing more photography-based stuff. It was super interesting to take these images of B.C. and Alberta forests, and shift the way a location looks. I feel like it really changes how you view a space, but also it’s a different world that you get to open up to other people when they come to see your work.

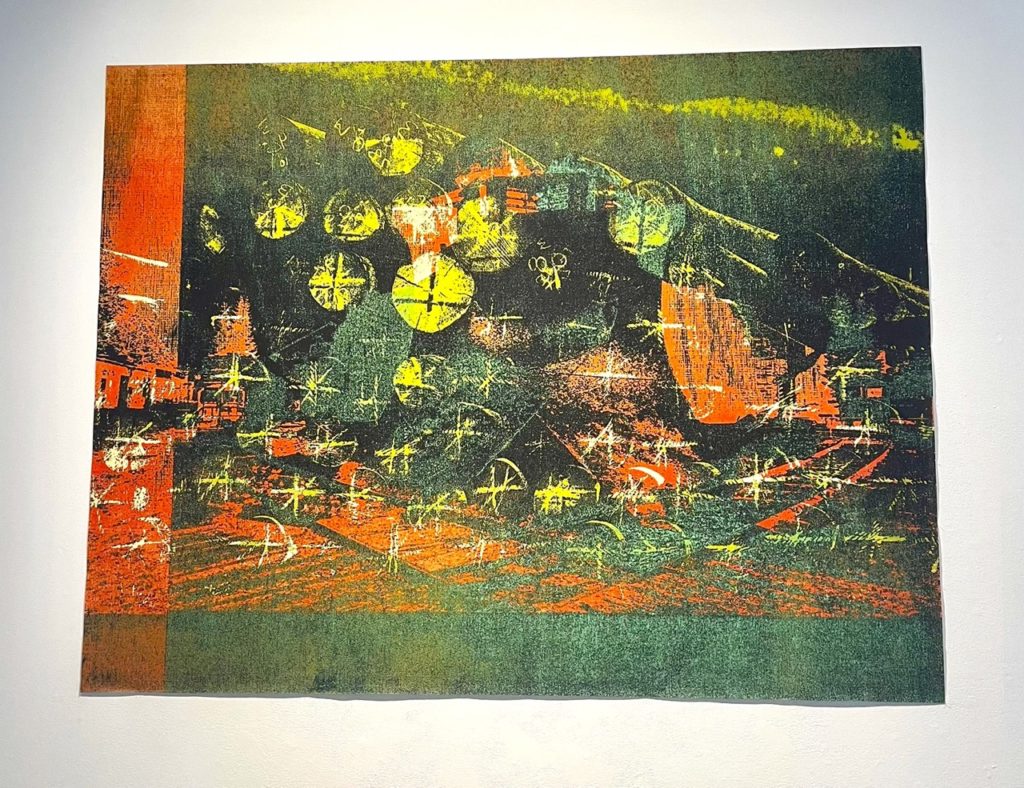

Q: Can you tell me more about ‘the executioner’s daughter’? What inspired the name of this piece?

Alissa: It’s one of those pieces that I really love, but I’m never sure why I love it so much. I think it’s probably the darkness that’s in it. It’s a very heavy image in a lot of ways.

The executioner’s daughter, which is related to the executioner, actually comes from the title of Angela Carter’s “The Executioner’s Beautiful Daughter” that I read as a teenager 15 years ago that I’ve always remembered. I went back to it, and I’m not embarrassed about it, but it’s a very problematic story with some very weird and disturbing descriptions of people. The story is about how the executioner of the village, kind of like the idea of police in a very simple way, is able to do all of the things that he’s executing people for.

This relates to the ideas of human hubris and technology and the way that we behave while thinking that there are no repercussions. It also relates back to the fact that climate change is on this very slow time scale where things that we did maybe 50, 100, 150 years ago are manifesting in the climate now, and what we are doing now is going to manifest within the climate in the future.

Q: Your piece, ‘postcard from the apocalypse: wish you were here’ immediately caught my attention. What is the significance of this piece to you?

Alissa: That one was kind of difficult to title because it really does feel like a postcard. It feels like there’s someone there standing out, like how we are currently observing all these climactic things happening around us, but in a weird way, feeling isolated from it.

The black framing and the black bars provide a space between the viewer and what’s on the other side. Even though B.C. has had forest fires and the smoke has drifted over to southern Alberta, there’s always this distance in it. And even though we are now starting to understand that it’s happening here, it all seems to be happening somewhere else, like the planes and the yellow-y soft hues in the distance.

The ‘wish you were here’ thing is cheeky because we are here, whether we like it or not. There’s also a weird serenity that I find in that one. This partly comes from memories I had had visiting B.C. when the fires were really bad a couple of years ago. I was stopped on this hilltop overlooking the Colombia River, and there was all of this smoke coming in from the mountains near sunset.

The sky was horrific and beautiful at the same time. This guy and his family had pulled up in a minivan and actually asked me to take a picture of them in front of this view. And I was like “what are you taking photos for in the apocalypse?”

So there’s a bit of that going into it too, this very surreal moment of “are you seeing the same thing that I’m seeing?”

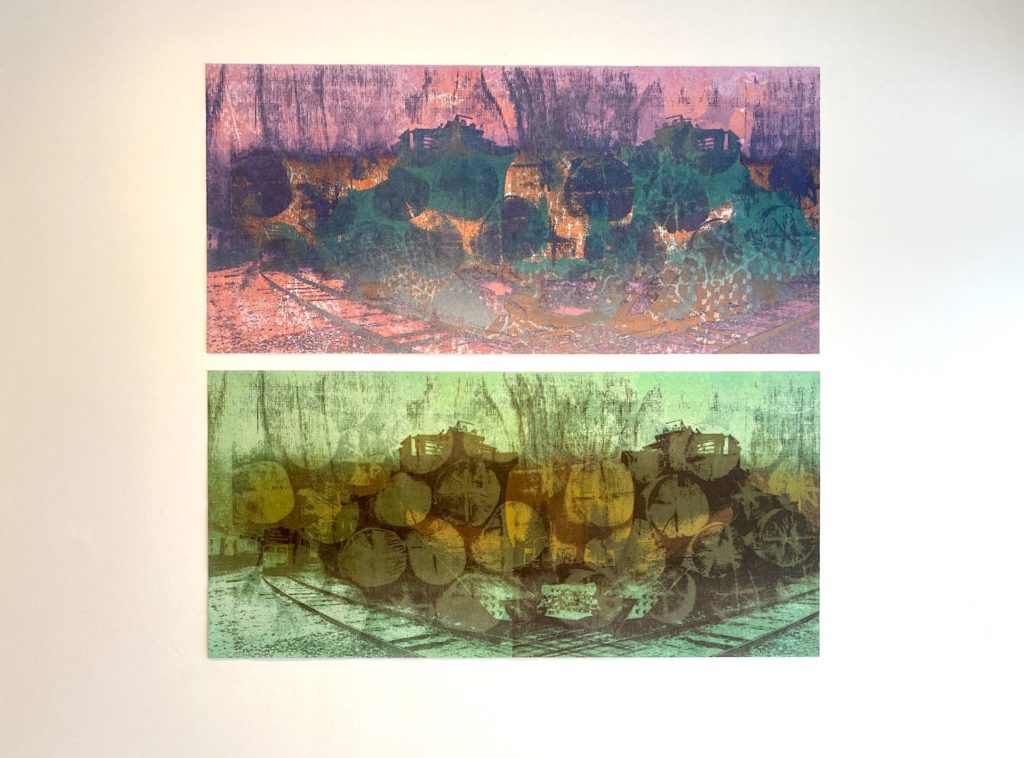

Q: The names and colours of ‘regeneration’ and ‘sorrow, mirth, funeral and (re)birth’ suggest hopefulness. How do those pieces fit into this theme?

Alissa: I think the hope in those ones is from the colour palette, because it’s a lot lighter but regeneration is more abstract. To me, it’s the collapse of human structures that starts taking on a new ecological life, whether you think of rust taking on a new ecological life, moss growing on something, or even animals building shelters within collapsed forms. Everything has been abstracted to a point where you can’t really tell what you’re looking at. And yet, it starts to emerge as a presence.

It also connects with the two pieces next to it, sorrow, mirth, funeral, and re(birth). The three of them work together because you have to go through regeneration, this really difficult destructive phase, in which there is a rebirth afterward. Even if the birth is something completely different than what came before, some people take solace in the idea that perhaps human life may not continue after the worst of climate change has happened, but other things will survive.

It’s cold comfort, but there will be a continuation of life in a different way. Sorrow, mirth, funeral, and (re)birth come from the rhyme in John Brand’s Observations on Popular Antiquities where if you see one magpie it’s sorrow, if you see two it’s mirth, and so on.

It’s a connection between the human and the ecological with the idea of fates being intertwined together. With the ecological being the fate-master, and its implied intelligence. And I love magpies, they are horrible, asshole birds.

Q: How do you hope students, faculty, and community members feel when they observe the art in your exhibition?

Alissa: The base idea behind The View From Where is to reassess how we relate to ecology, the way that we view it, and that’s informed by so many things such as the capitalism we practice, and the colonial histories here. It’s also informed by things going back to scientific rationalism and the enlightenment. We have these streams of thought that have constructed the western view of looking at ecology, which allows us to have extractive capitalism we are destroying the planet with.

I’m hoping that it gives pause to consider where these things come from, and consider the assumptions that are built into the ways we look at things. I want people to step back and see ecology from a different viewpoint, to see it without that lens of western thinking. This is really hard to do, but this is an attempt to pare away that lens. I think that we need to re-orient ourselves because we are not going to get through this if we don’t. So that’s my little bit of hope.