Loving the liminal: LGBTQ2S+ activists discuss identity at Students’ Union event

Rachel Narvey

Rachel NarveyIdentity is complicated, and how we see ourselves sometimes feels lost in the storm of preconceived notions others might push onto us.

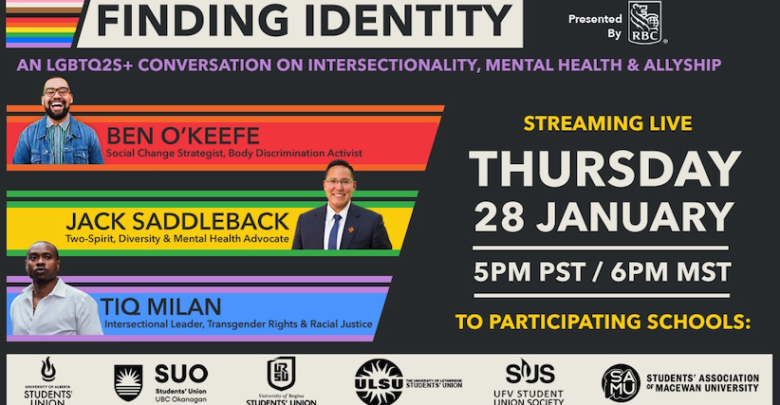

LGBTQ2S+ activists described their experiences of navigating perception and identity at a January 29 event, hosted by the University of Alberta Students’ Union. Moderated by transgender Youtuber Kat Blaque, speakers included Jack Saddleback, a Two-Spirit mental health advocate, Tiq Milan, a transgender writer, and Ben O’Keefe, a queer social change strategist.

Together, the speakers discussed the liminal nature of identity, ways to push past colonial paradigms of gender and restrictive masculinities, and how to make universities more inclusive.

Panelists discuss embracing liminality as a radical practice

Inititally, O’Keefe had struggled with the label “gay” when his partner began identifying as trans-feminine.

“There was a certain struggle that I had to deal with in myself, which was, how do people perceive me?” he said. “We sometimes assimilate … as opposed to just being that round peg that won’t fit into a square. You don’t have to fit the square, you can be a circle, and just embrace it.”

Milan described how others would approve of his relationships when they were perceived as heterosexual, but that approval would vanish when he spoke in a way that didn’t seemed queer.

“They would be like ‘that’s such a shame, [his wife] doesn’t know that her husband is gay,’” he said. “So for me, my desire, sexuality, and sexual orientation is about queerness and finding that space in between, beyond these rigid ideas.”

For Saddleback, a more expansive understanding of love can be found by connecting to traditional Cree teachings.

“You look at love medicine — sâkihito-maskihkiy — there was no definite answer about what that meant [in traditional Cree teachings],” he said. “[It was] not just love between a man and a woman, no, we understood that love is love. We as lonely human beings who are only one piece of the universe experiencing itself couldn’t say what that was supposed to be.”

Pushing past colonial paradigms of gender

Saddleback described growing up as a young gender-queer child in Maskwacis, home of Samson Cree Nation, where the fluidity of his gender was celebrated.

“Even though I had been assigned female at birth, I didn’t have to adhere to any sort of colonial gender,” he said. “I dressed the way I wanted to, I played how I wanted to, my family simply saw me as just Jack.”

When Saddleback moved to Calgary, he realized that the acceptance he’d found when he was younger might be more rare than he’d thought.

“It’s interesting to see how my growing up has shaped my understanding about the impacts that colonization has had on what we understand to be the human experience,” he said

He highlighted that terms like transgender man don’t directly translate to Indigenous understandings of gender.

“Heteronormativity, the gender binary, and colonialism are all connected,” he said. “Reconciliation and decolonization cannot happen unless Two-Spirit people are in all conversations.”

Milan describes seeking a “diverse, expansive” masculinity

Milan described how oftentimes, he is perceived as a cisgender man, and having that identity projected upon him comes with both privilege and baggage.

“I think about my identity as how I define myself, but also part of my identity is how I navigate that space of how other people perceive me,” Milan said. “I’m constantly in this place of trying to deconstruct what it means to be a masculine person, what it means to be a man and what it means to be queer.”

He explained how identity can be about “the experiences and opportunities” that he creates for himself, and for other people.

“As a masculine person in the world, I’m also intentional about creating space for feminine folks and women in my life to feel safe and to be their most authentic self.”

For Milan, engaging with masculinity has been about considering what lays outside traditional representation.

“I wanted to embody the masculinity that I saw in gay men and butch women,” he said. “That really showed me that masculinity was tethered to the spirit, that it didn’t have to be imposed by everything outside of it, that masculinity can be self determined … a diverse, expansive masculinity.”

He emphasized how different layers of his identity coalesce and inform each other.

“Being Black isn’t just about a race or being African American,” he said. “There’s also a divine experience that I’m having within my Blackness, there’s a divinity that I’m having within my queerness and my transness that kind of pushes my identity forward … I like to think of it as layers of identity, not fractions.”

O’Keefe also elaborated on how for him, identifiers and labels have sometimes felt more limiting than validating.

“So many of these identifiers are actually social constructs,” he said. “Even when I used to identify as gay, that was what someone telling me what I could be, not what I am and who I am. Now identify as queer because it can mean anything that I want it to mean.”

Transforming the institution from the inside out: how to change academic spaces

Blaque described her experience at an arts college, where many incorrectly assumed that the work of dismantling harmful ideologies embedded within universities had already been accomplished.

“People really thought ‘we ain’t gotta do shit here because we’re already weird and queer,’ but that wasn’t always the truth of it,” she said. “I’m really curious to hear what you guys have to say on the topic of making academic spaces more loving and accepting of their LGBTQ2S+ students.”

O’Keefe shared that despite getting good grades, he didn’t go to university due to how negative the experience of traditional education had been.

“My advice is to reclaim that space for you,” he said. “Education is such a major tool. Ignorance by its very definition is a lack of knowledge, the only way that we defeat it is through educating ourselves and others.”

O’Keefe listed some things schools could do, for example having bathrooms that people feel comfortable using and ensuring that people are safely housed.

“Also, what can you do to build community in your school?” O’Keefe asked the audience. “I’m going to flip this back and say that there’s a lot of power that you have if you are a person in this space, so what can you do to help someone else?”

Saddleback — who was formerly the president of the University of Saskatchewan Students’ Union — spoke about how there are still many underlying anti-indigenous sentiments within academia, specifically in terms of the worldviews they uphold.

“The interesting thing about higher education is that many of the individuals who go into [post-secondary education] will then go off into this larger colonial structure that upholds higher education in a larger class system,” he said.

“I love higher education, I love being able to break down these mentalities and systemic barriers in theory, but we need to do it in practice. So I implore people, I beg people, take that privilege that you now have with that degree and use it for good.”