Making space for the unaddressed: U of A research project focuses on black mental health

A U of A research project is providing black youth the chance to speak up about mental health

Helen Zhang

Helen Zhang A University of Alberta research project is creating space to talk about an issue the black community often sweeps under the rug.

A Participatory Action Research Project to Promote Mental Health of African, Black, and Caribbean Youth is an initiative led by nursing associate professor Bukola Salami, focused on studying how black youth mental health is affected by various societal issues. “Conversation Cafes” are one of the research methods utilized by Salami and her team, and the events prompt African, black, and Caribbean youth to discuss mental health and how it intersects with topics such as intergenerational relationships. The research project was funded by Policywise for Children and Families.

On November 25, Salami held the third of four “conversation cafes,” specifically focusing on black mental health through an intersectional lens. The event consisted of a panel of speakers versed in various aspects of intersectionality and small group discussions where participants considered how barriers such as sexuality or ability influence mental health and accessibility to resources.

Black mental health was set up to fail by colonialism, says presenter

One of the panellists was Rebecca Blakey, a co-owner of The QUILTBAG, a local LGBTQ retail shop. Blakey was happy to participate in an event tailored specifically for African, black and Caribbean youth, especially considering the strength community can provide.

“I love the contributions that ‘closed-space’ advocacy can accomplish,” Blakey said.

“To be able to gather together, [despite existing] in a position of being consistently considered the most abhorrent form of life, is the best thing we can do for one another.”

For Blakey, when discussing black mental health it’s necessary to think about the impacts of colonialism and how it intentionally set-up black mental health to fail.

“To me, every single mental health issue is locatable in the fact that systems of oppression exist to value some forms of life higher than others,” Blakey said. “Settler colonialism undergirds all of that and for settler-colonialism to function, white supremacy has to be in place.”

In terms of addressing mental health in the black community, Blakey said it’s important to understand the situation colonialism has created and in trying to survive, the black community must operate without infringing upon the rights of Indigenous people.

“Recognizing that the world as it exists on this land — we weren’t set up for success here,” Blakey said. “I just want everyone to do the best we can without doing harm onto anyone else inadvertently — solidarity with indigenous people and land back fundamentally undergird all of that.”

Mental health isn’t only for the white community

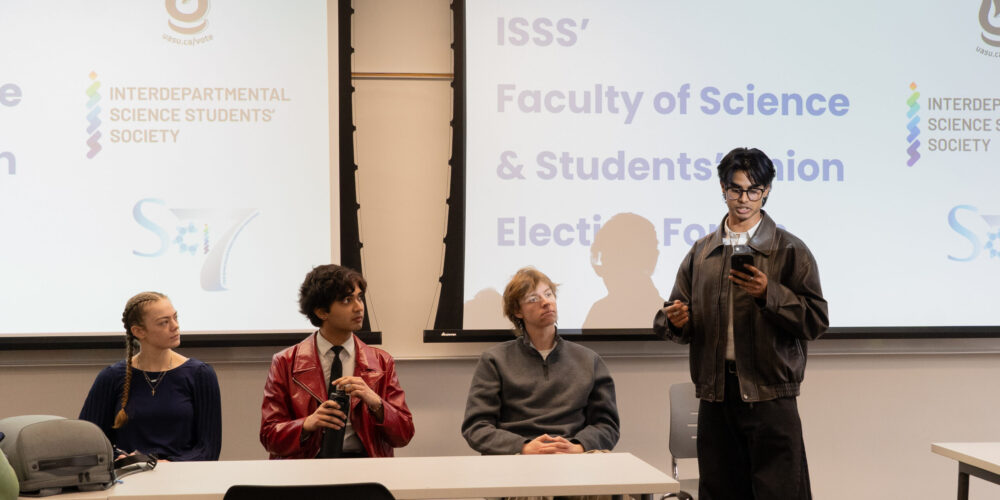

The “conversation cafe” was facilitated by community member Adama Bundu, third-year political science student Yar Anyieth, and third-year psychology student Nife Ajayi.

For Ajayi, creating a space to talk about mental health actively disrupts an inherited perspective of mental health, one shaped by the challenges of immigrant life in Canada. The idea of casting-aside mental health for the sake of survival is often passed down to first-generation youth.

“The majority of us are immigrant children — either first or second generation — and are coming from a lot of developing countries,” she said. “Mental health isn’t the focus because when you’re in a state like that, your focus is on food, shelter, water, money, the basic necessities.”

Despite this common narrative, Anyieth sees a large turnout as a sign that the community’s attitude around mental health is changing — evidence that black youth need and want spaces to vent out frustrations with peers that can relate.

“It’s exciting and really comforting to even have people attend,” Anyieth said. “They’re conscious of this, this matters to them. [Black youth] are taking small initiatives to put their well being forward and that in itself is a mission accomplished.”

Overall, a large aim of the conversation cafes is intrinsic to its name: to get the conversation around mental health started in the black community. For Anyieth and Ajayi, it’s time to break the long-held stigma that mental health is only for “white people.”

“I think that as a minority, you have a lot to lose when you’re not taking care of your mental well being,” Anyieth said. “In recognizing that it can have tremendous negative impacts, leading conversation, dialogue, awareness will hopefully push our community forward.”

“Just because we’re of African-descent doesn’t mean we don’t experience depression,” Ajayi added. “You’ll find a lot of our elders saying depression and anxiety are for white people, but we all experience it.”

For Bundu, facilitating a conversation cafe surrounding black mental health and intersectionality is about honouring the work black women and femmes did to push this theory to the forefront. It’s also a reminder that this isn’t a uniform issue, but is rather complicated by additional identities beyond black.

“Your existence within intersections is intrinsic to the level of traumas you have,” she said. “When you talk about mental health outside the complexity everyone holds in the world, it doesn’t allow for the different ways people are coming into the spaces. You can talk about mental health, but how is it also not being accessible to other people?”

Pictured: Adama Bundu, Nife Ajayi, and Yar Anyieth

Starting a dialogue around mental health may be a progressive first step, but Bundu emphasized that if the black community is serious about creating a dialogue around mental health, they must be willing to do so in an inclusive manner.

“[Intersectionality is] centring the people who are the most disenfranchised, who have continuously been erased or made to feel like they don’t have agency over what they contribute,” she said. “If I’m working to dismantle all these structures… if I’m moving forward, I’m taking the whole team.”