From the Archives: “The Book of Witches”

Khadra Ahmed

Khadra AhmedRecently, there has been a notable increase of interest in witchcraft. From modernizing shows such as Sabrina the Teenage Witch to increased interest in the religion 274 class studies in witchcraft and the occult, there seems to be a fascination with this once taboo religion.

In 1988, a manuscript depicting the view of witchcraft from the perspective of the Roman Catholic Church was donated to the University of Alberta. It’s contents, however, would lay undiscovered until 2005 when History and Classics professor Andrew Gow stumbled upon it.

The Gateway revisited a feature from the November 14, 2012 issue to re-live the discovery of this manuscript.

By: Katelyn Hoffart — The Gateway 2012-13 Staff Reporter

“The year is 1460 in Arrras, Switzerland, an area then known as the Duchy of Burgundy. Shifting ideals on magic and superstition have prompted mass witchcraft panic across Europe. Local women — especially prostitutes — are the main targets: the accused tortured in order to produce confessions. A monk known by Jean Taincture from the Dominican religious order, a group initiated by the Roman Catholic Church to battle heresy, begins to write the first treatise that gives an overview of European witchcraft, and the manuscript is passed down through the hands of many.

Fast forward hundreds of years to the 21st century, and the book has crossed oceans and continents to the University of Alberta’s Bruce Peel Special Collections Library. But lost amongst all the rest of the library’s treasures, its incredibly rare and unique historical insight remained unnoticed for years.

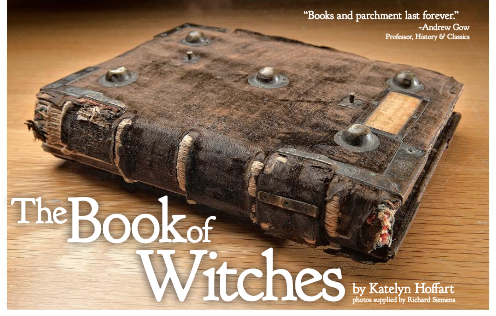

Faded brown velvet cloaks the thin wooden boards used for the covering — adorned with engraved dull brass bands, bosses and clasps to protect the now fragile book. Sections of the stringy binding lay exposed and tattered.

Originally catalogued under “Sermons Against the Sective Waldensians,” the label indicated that the subject pertained to the widespread religious movement during Medieval Europe that rejected priesthood and challenged the church.

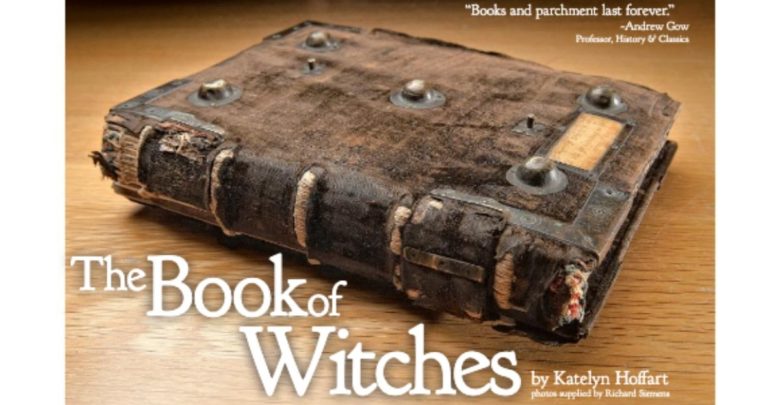

In 2005, Andrew Gow, a professor from the department of history and classics, was searching for teaching materials at the Bruce Peel Special Collections Library with his graduate student at the time, Rob Dejardins.

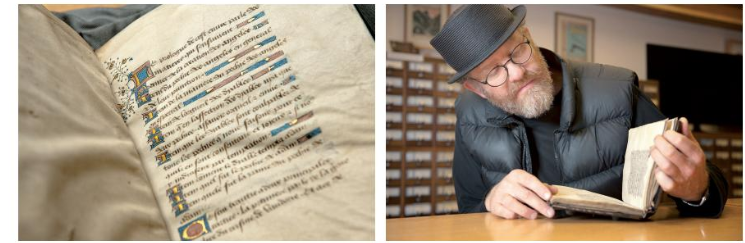

Although the label of the book didn’t pertain to the subject they were researching, curiosity led them to take a closer look at it anyway. They discovered that the perfectly legible elegant French handwriting written across animal skin parchment was actually about witchcraft.

Although the ornately coloured text comes across as strikingly beautiful, the subject matter is far from it. Dark descriptions of night orgies, devil-worship, hexes, and infant murder to grease flying broomsticks are just some of the written notions that reflect the intense hostilities toward women targeted as witches.

Gow described the writings as “over the top” literary fiction designed to explain some elements of the natural world — such as famine — that couldn’t be explained in pre-modern societies, as well as to explain societal conflict by blaming a supernatural force.

“It’s kind of a unifying theory that makes sense of everything — if you believe in the premises of the theory,” Gow said.

This made it extremely difficult for the accused to defend themselves against the ideas that were accepted by the mass population.

“The theory has always built in self-preserving mechanisms that say things like, ‘Witches typically will deny that there is such a thing as witchcraft or deny that they are mating the devil,’ in order to throw you off track,” said Gow.

He noted how prior to the mid-1400s, folk magic came to be associated with witchcraft was considered superstition rather than a crime to be dealt with through penance or prayer.

The idea that the devil was making earthly agreements with humans established the notion of diabolical witchcraft, which led to the beginning of state-sponsored witch hunts and trials.

“These are all invented by Romans against Christians, and then they’re just recycled, which is why we know that there were no diabolical witches. Because we know it’s a fantasy, we make up weird nonsense about our enemies in order to discredit them or make them appear truly dangerous,” Gow said.

Three known copies of the book were translated into French from the Latin original, one residing in Paris which contains the first visual depiction of witches riding broomsticks. The manuscript also once contained a colourful image of some sort, now only evident by a small corner of a page that was ripped out.

This particular copy is also believed to have been passed down through a variety of private collections, and it differs greatly from its Medieval French pen. This is indicated from an English inscription on the book that says, “On the Creation and Fall of Angels.”

Gow believes there is a chance that one of these owners was a notable aristocrat: King Edward IV — in exile during the War of Roses when the copy was made — is believed to have been sent this particular edition from the Duke of Burgundy, whose copy now resides in the Royal Library of Brussels.

The manuscript finally made its way into the U of A’s library as a donation by Dr. John Lunn in 1988. Originally, the book was appraised to be worth $4,200, based on its physical condition. Now that the content and identity of the book has been discovered, however, Gow describes its worth as “priceless.”

Gow, Desjardins and the rest of their small team have been working hard to write their own book with an English translation of the manuscript, as well as translated copies of all trails from the area when the panic broke out in Arras.

The translation of those Latin documents have proven to be more difficult, but an effort well worth the time. This incredibly rare find is a treasure that will be published to fuel fascination throughout the local, national, and international community.

“When not one single piece of digital text or audio recording is legible or available or findable, this book will still be legible. Nothing that we record today will be available in 1,000 years; this book will be,” Gow said.

“Books and parchment last forever.”