Richard Bagan

Richard BaganI’ve always loved YA novels. They’ve always felt like they were written just for me. I could see myself in the protagonists and hope for a world in which things were clearly right and wrong, where the good girl always got the guy, and where there was always a light at the end of the tunnel. But in some ways, I couldn’t see myself in those girls. They were all white, thin, and beautiful when they took their glasses off. They never seemed too concerned with sexism or racism, and the problems they faced could always be neatly wrapped up in 200 pages.

Novels for teenage girls have always been a site of exploration. Usually, their themes are personal: the young protagonists struggle with family drama, bullying, and even abuse and the death of loved ones, although these themes are often shoehorned in around a romance that takes centre stage. These personal struggles are important, but novels like this have typically shied away from the political. The main characters feel less like a part of a larger system than girls coming of age in a vacuum.

Growing up isn’t all puberty and high school drama. It’s also about coming to an understanding of how the world works: how cruel it can be, how unfair and unjust, especially for young women.

An amazing thing about the Young Adult (YA) genre is that it often centres the experiences of girls. More than in any other genre, YA novels feature heroines as their main characters, and that sends a message to young women that their inner lives are complex and worthy of exploration. What these novels have largely failed to do, however, is impress on teenage girls that they have the power to make change beyond the personal.

Ignoring the political in YA does a disservice to its readers: girls who often deal with racism, sexism, and other discrimination on top of the messiness of being a teenager. It’s becoming increasingly obvious that the stories we often tell about teenage girls — and the ones we think they’ll be interested in — sell these girls’ potential and power short. It is, in fact, possible to have a crush on the new guy in class while also fighting sexism at your school. It’s possible to be an active member of the Black Lives Matter movement and at the same time be worrying about when you and your boyfriend will have sex. That’s reality for girls. We contain multitudes.

The lack of political engagement in classic YA romance novels reflects how teenage girls have been told to behave: that their hormones and inexperience and gender mean they should devote the entirety of their brain power to planning for prom and thinking about their first kiss. Those things are important too, but the lives of teenage girls are shaped by the systems around them. They, as much as anyone else in this world, want to create change, and they’re well positioned to do so.

What they need are stories that show them the way, because words and narratives have the power to create new realities for us to aspire to and work towards.

There are YA novels now that are doing work that is explicitly and implicitly political. They are telling stories that I would have found world-changing as a 14-year-old and still find inspiring as a 21-year-old.

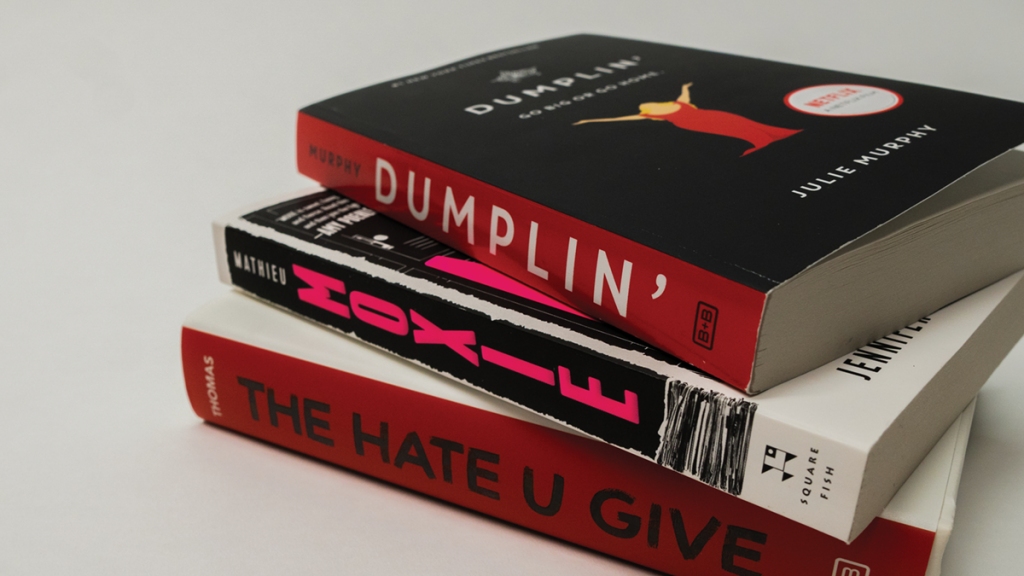

One of these novels is 2017’s Moxie by Jennifer Mathieu, which tells the story of a girl who starts a feminist zine highlighting the misogyny at her high school. But the examples of sexism that Moxie’s protagonist Vivian Carter endures and pushes back against also feel universal — double standards, sexual harassment, and unfair power structures are examined on the hyper-local level, but we know they are emblematic of the sexism young women will continue to experience as they enter the “real world.”

What Mathieu does particularly well is blend the tropes of YA romance with these political issues. At the outset of the novel, a new boy, Seth, moves to Viv’s small-town Texas high school and quickly becomes intrigued by her. Mathieu doesn’t shy away from this romance — Seth becomes a male ally, an example of how boys can support girls. At the same time, he isn’t unrealistically perfect and struggles to understand what his role is as a guy in the feminist movement.

Mathieu also fractures Viv’s high school in a predictable way. There are the typical cliques — jocks and popular girls and unassuming nice girls like Viv herself — but these labels are always more than they seem. The football players are more sinister, their entitlement more dangerous, the repercussions of their actions more far-reaching. The popular girls surprise you, and the unassuming girls become the most outspoken. In Moxie, cliques of girls band together across racial and popularity lines to amplify each other’s voices and push for justice. Along the way, Mathieu highlights conversations around feminism that feel real — some girls proudly wear the feminist label while others shy away from the controversy surrounding it. Importantly, there are girls of colour in the novel who question the lack of intersectional understanding that has plagued the feminist movement, and who become leaders at their school.

Ultimately, Moxie’s lesson is one of speaking up without drowning others out. I came out of reading it with the feeling that things can change, and with the overwhelming urge to make my own feminist zine.

Another recent YA novel that left me similarly inspired is Julie Murphy’s Dumplin’, which was published in 2015 and has just been turned into a Netflix movie. Dumplin’ follows Willowdean Dixon, a plus-size girl (also in Texas) who enters a beauty pageant to prove she can. Willowdean’s story is not a weight-loss journey; it’s about how the quest for perfection that all women are expected to relentlessly pursue is a mirage — that by comparing ourselves to each other, nobody wins.

As a character, Will (as her friends call her) is inspiring because she’s not as confident as she seems. The persona she projects hides real insecurities that most girls can probably relate to. She must overcome obstacles — her own judgmentalness, her relationship with her mother, her feelings about her aunt’s death — before she can genuinely accept herself.

Dumplin’s message isn’t explicitly political, but having a story starring a fat girl who doesn’t want to lose weight still feels radical. Will is not singled out as especially tortured or inspiring because of her weight. She is flawed and self-conscious, beautiful and loved. She feels real.

Murphy also complicates what could be a straightforward feminist takedown of beauty pageants — while Will enters the pageant in protest, she comes to see how the contest can lift young women up… in some ways. At the same time, the hyper-femininity of the pageant is paralleled in the cultures of drag queens and Dolly Parton, and celebrated as well as critiqued. Murphy sets up stereotypes just to knock them down by the end of the novel — it feels refreshing in a genre that relies heavily on mean girls and bad boys with hearts of gold.

Out of all these novels, Dumplin’ feels the most like a love story. Will’s romance with Bo, and the way it triggers self-consciousness she didn’t know she had, takes centre stage for much of the story (something the movie largely glosses over). It’s a relationship that ebbs and flows, that’s complicated and messy and that you root for all along — a perfectly imperfect YA romance, something Will deserves.

While Dumplin’ makes the personal political, Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give is a political movement made personal. Published in 2017 — and already made into a movie — The Hate U Give follows Starr Carter, a black girl whose friend Khalil is shot and killed by a police officer right in front of her.

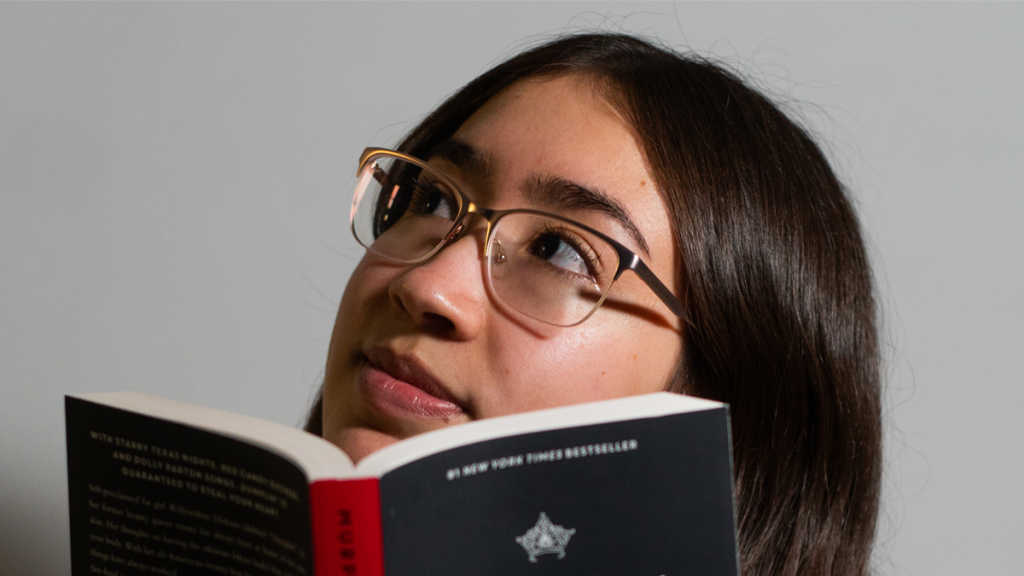

The book is a 464-page indictment of anti-black racism in America, but in the form of a coming-of-age story. Starr is not just a girl whose friend was killed. She’s not even just an activist. She’s a teenager with friend drama and boy drama and family drama. But radically, Starr is black. This fact is so unusual for a YA novel that I don’t think I’ve ever read another story featuring a black girl as the protagonist. If teenage girls haven’t been given a voice, then teenage girls of colour have been the most silenced. The Hate U Give pushes back against that lack of representation, centering the reader within Starr’s narration. Her voice is loud; it can’t be shied away from.

Starr’s narration is one of the novel’s strongest features. The reader gets to experience the way she navigates the different parts of her life, code-switching — changing her pattern of speech — to reflect whether she’s in her neighbourhood, Garden Heights, or at her affluent, predominantly white high school. Non-black readers may find Starr’s language and references confusing or alienating, and their own discomfort is, in itself, a powerful message.

Similar to Moxie, The Hate U Give brings up different opinions about the Black Lives Matter movement. On the news, police brutality is debated, and in Starr’s high school, her own (non-black) friends discuss Khalil’s death. This discourse is a reflection of the conversation happening around Black Lives Matter in the real world, and Thomas gives young women a blueprint for talking about these issues with those who don’t — or won’t — understand. But she doesn’t just paint a sanitized version of this reality — there are protests and riots, rubber bullets and tear gas. It is in this context that Starr finds her voice. As commentators blame Khalil’s death on everything but the police officer who shot him, Starr discovers the power she has to make a difference — and all the danger that comes with it.

Now I feel myself more drawn to YA novels than ever. Throughout my life, these books have taught me lessons about mental health, heartbreak, friendship, and family — they’ve shaped me. I’m excited to see this genre moving and changing as our understanding of teenage girls and what they care about expands. Every time I think of a girl picking up one of these novels and learning something new about feminism, or Black Lives Matter, or even Dolly Parton, I feel hope.

Vivian, Willowdean, and Starr show girls that being brave doesn’t mean being unafraid; it means pushing past that fear to speak out against injustice. They are the girls we should be holding up as aspirational — not because they get the guy or because of the way they look, but because of their power. The success of Moxie, Dumplin’, and The Hate U Give shows that teenage girls want YA novels that acknowledge their voices and show how to use them. We should listen to them.