Rebecca Lai

Rebecca LaiImagine a wildfire rapidly engulfing your hometown. Your dad rushes through the door after talking to the neighbours and screams, “We have to evacuate now!” Mom is at work and your younger sister is still at school and you can’t help but worry if they’ll make it out of town.

You don’t know where you’ll go or for how long, so you frantically pack clothes and toiletries. You and your dad lock the front door, not knowing it would be the last time, and then desperately drive your way out of the neighbourhood. There’s bumper to-bumper traffic that lasts three hours on what’s normally a six-minute commute. While stuck in traffic, you look up at the sky — it’s black, ashes are falling down, it smells smoky and hot. The uncertainty and desperation to get out safely stifles you.

Your two uncles join you because they ran out of gas. Everyone tries to decide if you should go north towards the oil camps or down south to Edmonton. Your uncle calls the police to ask for advice and they say they don’t know; just get out of the town. When you arrive downtown, it’s completely abandoned and so smoky you can’t see the buildings on Franklin Avenue anymore. You’re greeted by police officers who tell you to take a certain road, and soon everyone in the car is shocked to see the trees and bushes on fire as you drive next to them. The smoke is slowly moving closer but your family decides to spend a night parked on the highway to save gas.

On May 3, 2016 the common icebreaker question, “If your house was on fire, what would you save?” became a reality for everyone living in Fort McMurray.

You don’t want to drain your phone’s battery, but you go on Facebook to update your friends and family and call kind strangers who are offering to bring gas. You can’t help but feel hopeless, and you can’t comprehend everything that’s happening. It’s not until the next smoky morning that a stranger knocks on your window mid-nap and offers you enough gas to reach Athabasca and eventually Edmonton — where you get to reunite with your mom and sister who took one of the first buses down.

I was born at the Northern Lights Regional Health Centre in Fort McMurray. I grew up in a blue house, riding bikes with the neighbourhood kids after school, playing hide-and-seek, squishing a pop can into our back tires so we would sound like motorcycles — our street probably despised us. My sister and I loved to collect rocks and worms after it rained, and on the weekends our dad would always drive us to McDonald’s.

On hot summer days, my mom would take my sister and I swimming at Centennial Pool. Then she would get us pizza, a rare Western treat from the type of Asian mom who can’t go a meal without rice.

Fort McMurray is a place where people come for the money but stay for the community. It has everything you need to get by: multiple Tim Hortons, rivers surrounded by bright evergreens, and the glowing aurora borealis.

About 88,000 people evacuated Fort McMurray in the first week of May 2016, fleeing to Edmonton or other neighbouring towns. My family stayed at my uncle and aunt’s house on the northside of Edmonton. Over 15 family members and work friends were staying there, filling up all the rooms. Some of us had to make makeshift beds on the floor.

The evacuation lasted for about a month before re-entry plans were implemented in June, but one silver lining is that it brought everyone together. Every day was eventful as we looked for something to keep us entertained other than helping everyone fill out the evacuation papers and unemployment forms. My dad and uncle are cooks, so we had the best food every night, and it felt like a party with the amount of people eating together.

The Fort McMurray wildfire made worldwide media coverage. People called it “The Beast” because it had a mind of its own. It would die down but come back even stronger. My relatives in Hong Kong and Texas were worried about us and wanted updates every day via FaceTime.

I remember waiting outside the Butterdome for three hours with my family to collect government funding for evacuees. Strangers living near campus offered us water, muffins, and sandwiches. Those small acts of kindness warmed my heart.

My family held out hope that our house would be untouched by The Beast, but within the first week of the evacuation, the municipality released pixelated satellite photos of our neighbourhood that showed that our street had been the only one affected. Our home had burned to the ground. My family lost everything.

The Beast had destroyed 2,400 houses and buildings — and my house was one of them.

What hurt me the most was losing VHS tapes of my grandma living in Fort McMurray, and sentimental items from my grandparents like pictures on their shrine and baby photos of my sister and me — they could never be replaced. Why hadn’t I saved more? Why did this happen to my family?

Almost all of the evacuees were given the chance to visit their homes and attempt to recover items with help from professionals. When it was my parents’ turn, they found our basement flooded with water up to the workers’ knees. It seemed unlikely they’d be able to recover anything.

I remember my dad telling me that he had to beg the workers to at least try to recover our fireproof safe. After many attempts, they were able to get the safe and pry open the damaged, burnt door. Surprisingly, we were able to recover several of my dad’s two-dollar Canadian bills, jewelry pieces that belonged to my grandma, and old passports. It wasn’t much, but we remain grateful for the items that were saved.

I didn’t know how affected I was by the fire until I moved to Edmonton in September 2016 for university while my family was in Fort Mac. The new people I met asked me where I was from a lot, and when I told them their faces lit up with empathy and curiosity. Some asked about the fire, but many didn’t. I think they felt too uncomfortable, or maybe they had forgotten about it.

I found myself needing to buy the most basic necessities like socks and pencils. It felt like I was starting my life from scratch. Lots of people told me the things I lost were just things, that the memories are more important. While that’s true, I needed time to mourn the loss of my home and the things I could never get back. I needed an outlet to express my feelings and gain a sense of closure.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve loved art. Pursuing it as a career wasn’t my first choice, but I decided to take the risk and study art and design at Keyano College, a community college in Fort McMurray. While I do enjoy creating art, I felt that design was my calling and wanted to push myself by continuing my education at the University of Alberta after my first year.

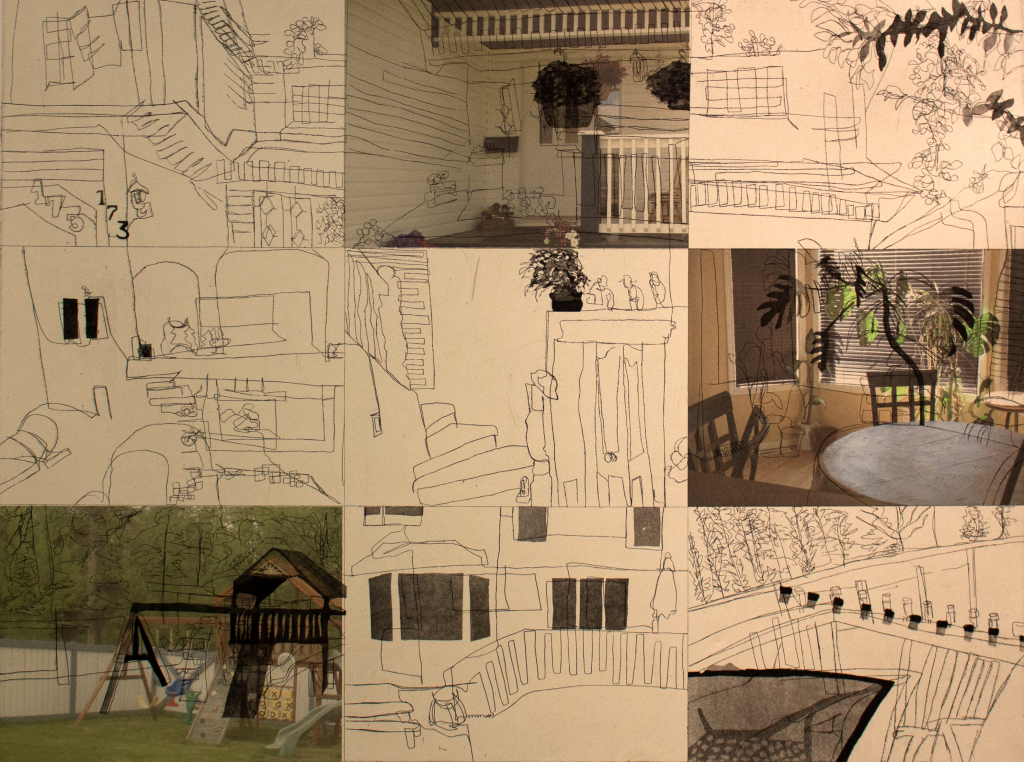

In my second-year design classes at the U of A, we were introduced to the importance of storytelling. For our first self-directed project, I decided to design a memoir about the wildfire. I wanted to be able to write down my feelings and let the memories fade away.

When I created my memoir and prints about the fire, I was in a different stage of recovery for each project. Now I look back on the adversity that happened more than two years ago through a different lens.

After the fire, I constantly felt guilty because I was forgetting what happened during the evacuation. I would find myself closing my eyes, trying to relive it so the feeling would stop. But pouring my emotions onto the page made me let go of my memories of the fire. Designing the memoir let me tell my story, for myself and to educate others.

I thought that project would be enough to gain a sense of closure and move on. Yet, I found myself still talking about the wildfire a year later. I realized I was still mourning. So in my third year, I decided to base my printmaking theme for the semester on the fire. I wanted to explore my journey of resilience through the artistic process. By the end of the semester I had created three different series of prints: “Closure,” “Memories at 173,” and “Fresh Start.” These prints represent the progress of recovery that the people in Fort McMurray were experiencing.

When I created my memoir and prints about the fire, I was in a different stage of recovery for each project. Now I look back on the adversity that happened more than two years ago through a different lens. The road to resiliency isn’t easy, but I’ve learned how to bounce back from the worst times.

Sometimes, memories from the fire resurface in the news or on social media, and I’ll suddenly remember that it actually happened. Once, I watched the Discovery Channel’s Fort Mac Wildfire: Rogue Earth with my friends, and it was so surreal to watch a documentary on Fort McMurray — a town that no one in the world really knew about before the fire. My family was able to move into our new house on the same lot in Fort Mac this past summer. I can’t speak for everyone, but my family has moved on from this tragedy. And while my house was being rebuilt, so was I. Fort McMurray will never be the same — and I’ll never be quite the same either.