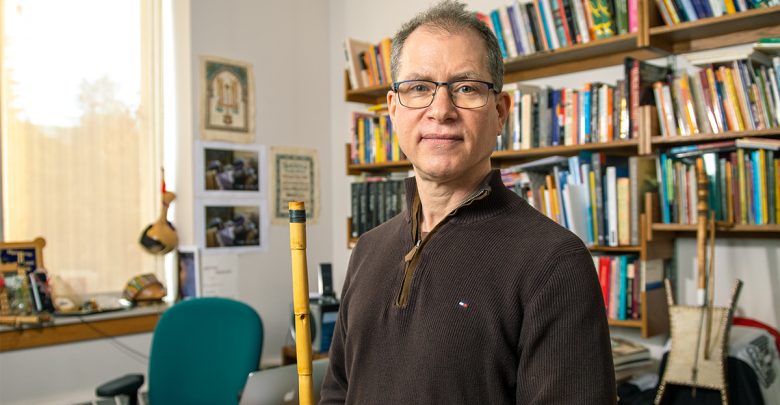

UAlberta Campus Connections Award winner uses music as “social technology” for community change

Michael Frishkopf's work in ethnomusicology is developing the vision of what it means to be human

Richard Siemens (2018)

Richard Siemens (2018)To a lot of people, music and analysis may seem incompatible. But to Michael Frishkopf, U of A Professor of Music and Director of the Canadian Centre for Ethnomusicology, they are two sides of the same coin.

With a BSc in Mathematics from Yale, Frishkopf originally worked as a computer scientist, before an interaction with a West African music group’s leader — who was an ethnomusicologist — turned his sights toward ethnomusicology, which is the study of music’s cultural and social aspects. In recognition of his local and international work to strengthen people and their cultures around the world through music, Frishkopf received the 2018 University of Alberta Campus Connections Award.

Since 2007, he has been the leader of Music for Global Human Development, a multifaceted international project dealing with the social, cultural, economic, therapeutic, and health benefits of music in communities around the world, including Edmonton’s diasporic refugee communities and those in Africa and in the Middle East.

“I’ve taken to calling music a social technology,” he says. “If you can create a feedback loop by crossing enough boundaries, you’ll be able to bring a larger vision of what it means to be a human being together. This happens in the face to face.”

According to Frishkopf, ethnomusicologists must contextualize theory with first-hand experience, which he has committed to sharing with others. As founder of both the U of A’s Middle Eastern and North African Music Ensemble and its West African Music Ensemble, Frishkopf promotes dialogue and rapport between different musicians, including both students and community members engaging with their culture. Under Music for Global Human Development, he teaches courses in the Faculty of Arts in which students work with Edmonton’s immigrant and refugee communities.

“The collaborative aspects of these projects are very important to me,” he says. “It’s empowering, it’s ethical to include people as project partners, and it’s sustainable because once they’re a part of it, they can take it away and do it on their own.”

As for the future? Frishkopf is working to expand student experiences outside of the classroom and has a fieldwork trip to Ghana coming up. He is also planning to further develop his Deep Learning for Sound Recognition initiative, a project designed to enhance the listening capabilities of AI. Frishkopf says this project has practical applications for many sound-based academic fields, like linguistics, anthropology, and bioacoustics, as well as ethnomusicology’s need to categorize, sort, and understand music. In all of Frishkopf’s projects, he aims to lay the groundwork for the protection and expansion of cultures to come.

“I like to say that everything we do as academics has some kind of impact on the world, however indirect,” he says. “Music has the power to not just bring the knowledge out, but change the attitude that people might have about a particular subject.”