Q&A: Petar Dundjerski, U of A Symphony Orchestra conductor, on Rachmaninov

Kesia Dias

Kesia DiasThe University Symphony Orchestra (USO) ended their semester on a high note at the Winspear Center for the Arts in late March.

The group made up of many talented musicians balancing challenging degrees would meet twice a week on Monday and Thursday evenings, in preparation for this momentous finale. The concert included the U of A’s Voice and Opera singers that accompanied the Orchestra and featured the debut of Gregory Mulyk’s orchestral composition.

The magnum opus of the concert performance was the rendition of Sergei Rachmaninov’s last orchestral piece, “The Symphonic Dances.” This mentally and technically challenging piece was performed beautifully by the USO group and well-received by the awed audience.

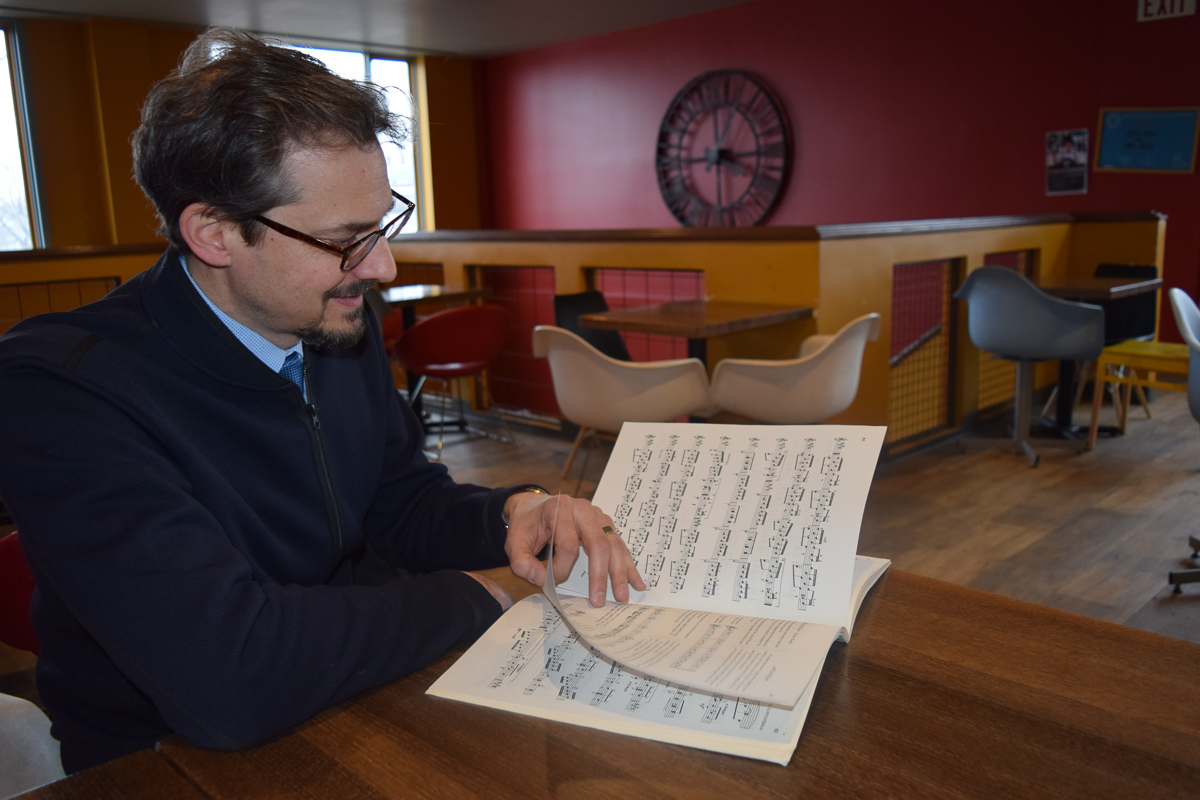

We met with Petar Dundjerski, the talented conductor of the group and a professional flautist, to find out more about the USO group and the pieces they chose for the concert.

The Gateway: Can you tell me more about how you chose to become a conductor? Why did you choose to be a conductor at the U of A?

Petar Dundjerski: I chose to be a conductor before I came to the U of A. I do remember that when I was 20, I knew I wanted to conduct after playing the flute for many years. There are pieces of music that are just not available to the flute. Some of the greatest music is written to solo music, but once you are part of a group with 60 to 80 people, or 120, you are all on the same page, literally. You are all going to where the composer wants to take you.

Ultimately you don’t make a sound as a conductor. You must always bow to those you make a sound. That said, we are there together and there is some flow of energy between us. If left uninterrupted and unobstructed, it truly is special. It is part of a bunch of notes and symbols that the composer wrote that allow the conductor to create this Great Wall of China of sound.

How do you keep your students motivated to learn these challenging pieces?

It is a constantly evolving process. Positively, by encouraging them constantly, by complimenting the visible developments, making sure their efforts are appreciated and noted. The negative approaches do not ring true anymore.

Tell me about the Rachmaninov piece.

Rachmaninov makes musical references to events in his life or in the history of music. They are put there in order to tell a story. This story is him summarizing his life as an artist and as a human being. He died three years after composing this piece. (Rachmaninov) has definitely been around the block, and was feeling some things that prompted him to summarize his life. In the last movement, the most religious of the movements, he basically looks for transcendence. “Am I able to be at peace with God, with what I went through in life? Was there a point to it? Does evil or the good win in the end?” He had a fabulous career as a pianist; he was the greatest pianist of the 20th century. He found a way to write tonal, melodic music that was very original.

The U of A’s voice and opera singers are also part of this concert. Can you tell me about that?

In the department, we have more than just strings and wind players; we have composers and the opera workshop, so we wanted to include as many people as possible. We approached (them) and asked if we could do something with them. They are performing six numbers from the Mozart’s last opera. All the operas are sung and this opera is called a “singspiel,” which is roughly translated to “sing and play.” There is a dialogue between the orchestra and the singers. They translated the dialogue from German, and the dialogue in between is in English. They were able to put the action of the opera into words.

That leads us to the last piece. We approached the compositional department and they assigned a student composer for the task.

How did the orchestra learn the piece by Gregory Mulyk?

You hope the composer is clear and anticipatory of what the orchestra is supposed to sound like. Some things work great on paper and when a composer writes a piece, it is perfect in his head. The picture will be different enough when played by the orchestra. Those changes are fairly general, it is simply fine-tuning.