Supplied

SuppliedContaining ice cores that date back more than 100,000 years, one of the coolest (literally) archives has been started at the University of Alberta.

A collection of ice cores reaching a total of 1.7 kilometres in length are being housed in the Central Academic Building (CAB) after being kept in Ottawa by the Canadian Government. At the U of A, the collection will be used for research, Jeffrey Kavanaugh, an associate professor of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, said.

The new facility in CAB is equipped with instruments to analyze the cores, which were funded by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council grant.

“We’re hoping that this facility inspires a new generation of ice core scientists and ice core studies,” Kavanaugh said. “We’re also hoping that Canadian researchers and researchers from around the world take advantage of these cores and the analytical capabilities that we’re building here.”

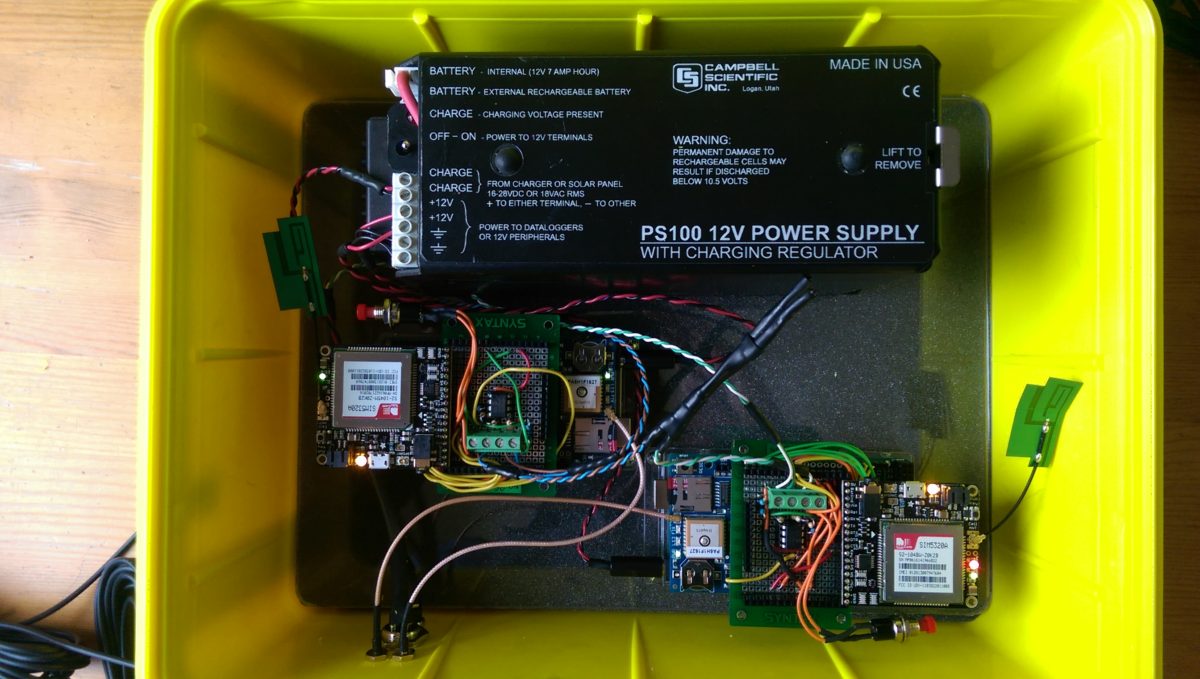

The dozen ice cores contain records of atmospheric and temperature conditions were trucked to campus earlier this week. Kavanaugh built a program to monitor the temperature of the ice as it traveled to the U of A to make sure it doesn’t melt.

“It would be rather tragic to spend the money and time to develop this new facility and all the effort to transport the ice,” he said. “And then to open it up and find the freezer had failed and we had a bunch of tubes of water which would destroy their value completely and utterly.”

The location and temperature of the ice on its 3,000-kilometre journey was tweeted out and texted to Kavanaugh. If the temperature had rose above -18 degrees Celsius, truck would have had to reroute to a freezer facility, but that didn’t happen.

Since the ice needs to be melted for proper study, priority will be given to scientists answering important questions, Kavanaugh said. Some ice will also be preserved for future analysis when new tools are developed as well.

Kavanaugh himself is focused on obtaining new ice cores to add to the library including samples from the ice fields in the Rocky Mountains, the arctic ice caps, and Yukon’s mountain ranges. It’s important to collect new ice cores before the ice fields retreat with climate change, he said.

“That record of past climate is disappearing,” he explained. “Every year that the ice retreats is a portion of the record that’s lost to us. It’s critical that we obtain cores from the ice fields of Alberta as soon as we can.”

Ice cores are important for a number of reasons, according to Kavanaugh. One example in Alberta involves chemicals — poisonous chemicals humans used in the past are still present in ice fields that provide water to Albertans and could be reintroduced into the water supply.

“Understanding how that reintroduction (of chemicals) will happen is important,” he said. “And it’s not just climate change; there are a lot of other social issues we can look at by examining the ice.”

Kavanaugh, who teaches a course on environmental instrumentation, encourages students to develop tools to answer research questions, such as the program he created to monitor the ice cores. He also uses instruments and weather stations to look at how glaciers flow as far south as Antarctica.

“Any tool you can add to your toolkit, be it electronic or a different spoken language, can be a game changer for your own understanding,” Kavanaugh said.