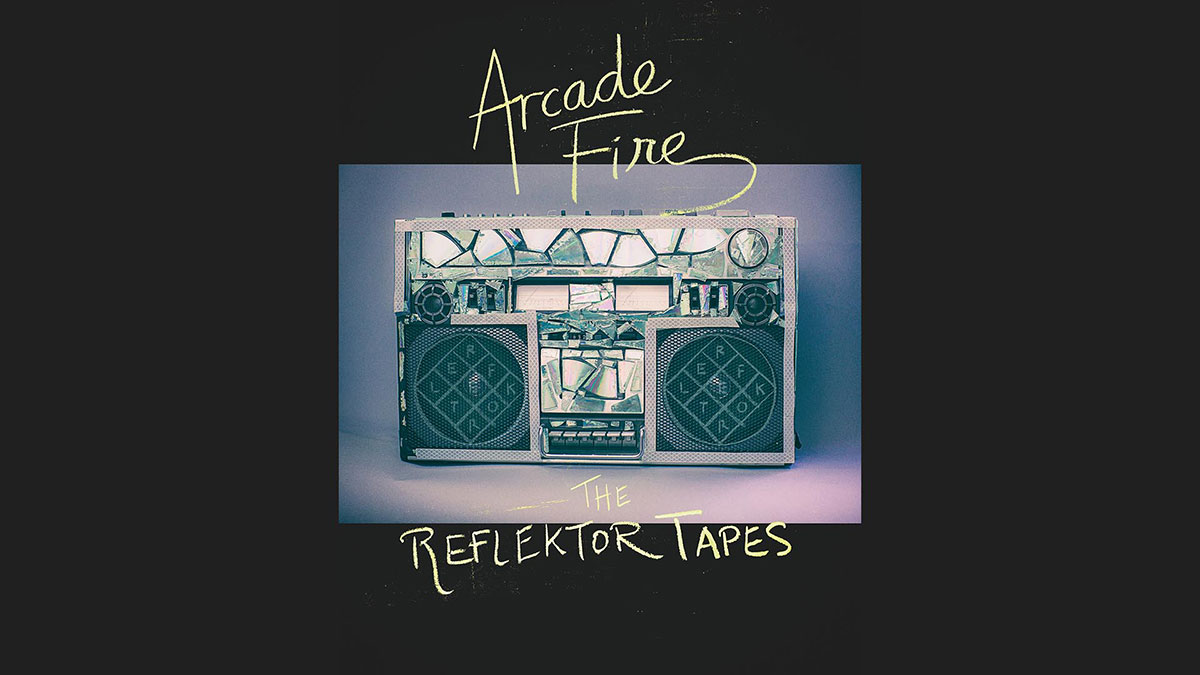

Movie Review: Reflektor Tapes

Supplied

SuppliedIt’s been two years since Arcade Fire released Reflektor, their highly anticipated follow up to The Suburbs. The latter LP earned indie rock its first Album of the Year Award at the Grammys, but the trophy came with the burden of showing the world that their recent upgrade to superstar status wouldn’t have an adverse impact on their songwriting.

Reflektor was a wonderful response: a bold album with an edgy sound that differed significantly from the group’s previous LPs. The sonic adjustments — grittier basslines, more focus on rhythm and greater tendency toward experimentation — were a defiant declaration that the group would prefer to risk losing old fans than attempt to gain new ones. Reflektor occupies an important spot in the group’s discography, and while many would dispute the claim that it is their finest album it has a certain quality that makes it almost immune to criticism. It’s their White Album.

Two years after Reflektor’s release, L.A. based film director Kahlil Joseph has renewed interest in the album with his documentary that follows Arcade Fire in Haiti during the period leading up to its composition and in Jamaica where it was eventually recorded. Joseph’s previous work includes the riveting short film When the Quiet Comes for Flying Lotus as well as the music video for FKA Twigs’ Video Girl. In The Reflektor Tapes, Joseph pays tribute to the rich musical traditions of the Caribbean by exploring Arcade Fire’s immersion into rara — Haitian street festival music — and the subsequent influence of rara on their sound as they quickly become intoxicated with its energy and pulsating rhythms.

Joseph’s nonlinear directorial style shares much in common with the album itself. He tends to wander in ways that are at once epic and aimless. His high frequency of splicing establishes a non-continuity that complements the underlying chaos of Reflektor, evoking its dizzying but often exhilarating tempo changes. Joseph also includes a large quantity of scenes depicting Haitian urban life, at times using a split screen format to layer the footage alongside shots of Arcade Fire’s concerts in North America. The visual effect of sold out arenas next to Haitian street festivals powerfully contrasts the different ways in which music is distributed and enjoyed in different cultures. It’s doubtful that this technique is intended as a direct criticism of Arcade Fire given their history of advocacy for the people of Haiti, but it does seem to be suggestive of the general tendency of capitalism to subsume the cultural practices of developing countries.

A notable implication of the film’s irregular and fractured style of delivery is that lengthy exchanges of dialogue are few and far between in spite of the numerous interview clips utilized. Its quest for experimentation leads it far off the beaten path and the film actually reveals surprisingly little about either Arcade Fire or their album. This is not to suggest that it fails, only that its title is misleading. The Reflektor Tapes is not so much about Arcade Fire as it is about the band’s fascination with music, or more generally, a universal fascination with music as portrayed through the curious eyes of professional musicians. From this perspective, the lack of dialogue is effective because it emphasizes the superior communicative power of music and its ability to go to lengths that speech can only dream of.