Family hopes student’s suicide can be a ‘learning opportunity’

Supplied

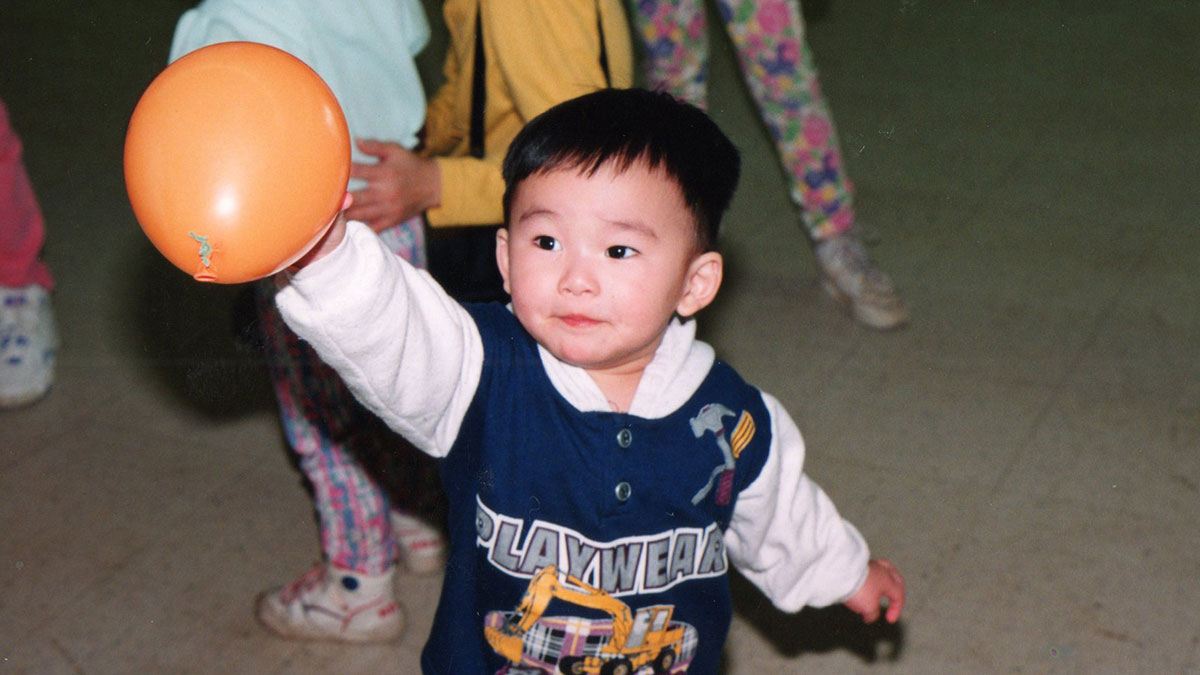

SuppliedEvan Tran’s infectious smile could transcend an entire room.

Tran’s delightful and quirky grin that stretched from ear to ear whenever he unfurled it is what those around him remembered him for. The signature beaming sign of affection, which seemingly never left Tran’s face, was a glowing reminder of the generous and caring person Tran was known to be. To classmates and the campus community, Evan is remembered as a jokester and someone who was positive and happy all the time.

But that was just one side of who he was.

Tran battled with depression and mental health issues ever since he was 15 years old. He never expressed those feelings to his classmates or friends, but when he was at home, where he felt most comfortable, he was sad and melancholic. There were no warning signs for his friends at school.

His oldest sister, Vanlee Roblee, didn’t know about his “surreal” double lifestyle either.

After Evan would put on a bubbly personality at the university, she remembered him coming home and questioning why his brain wasn’t working properly. He couldn’t formulate any memories while studying. Something that should’ve taken him two minutes to read took him half an hour.

He sought help. Tran took prescribed medications and regularly saw a psychologist. He tried to overcome his bout with depression, but he was unsuccessful in trying to save himself.

On Sunday, Oct. 11, Tran was reported missing. He was last seen leaving for the university to study and was scheduled to meet his parents at the Golden Rice Bowl restaurant at 7 p.m., but never showed up. After Roblee and her husband, Colin, posted pictures of Tran to Facebook while urging others to spread the word, a flurry of social media posts ensued. But after a visit to Roblee by the police, the search was called off.

Despite his prolonged battle with mental health issues, Roblee was still in “complete shock” when she found out her brother had committed suicide.

“We were aware, but maybe just not how bad it was,” she said of his depression. “Honestly, if I knew, I would’ve stepped in. I would’ve said, ‘you need help now.’ But it’s hard, because you’re navigating something where you don’t want to escalate a situation that may not require it.”

Angela, Tran’s second oldest sister, said the pressures he faced in university were internalized and kept hidden from his friends at school. Tran, like many university students, put unrealistic academic expectations on himself. The two talked about failure often. Tran couldn’t help but hold himself to certain academic standards, many of which he didn’t achieve.

He had setbacks, but never discussed them with his friends at school. He thought it was “shameful” for his friends to see him like that. Tran gave them no indication of who he really was or how he would truly feel.

That attitude, the embarrassment of knowing when you need help, is what Tran’s family is trying to overcome. They see the tragedy as a learning experience, not just for them, but also for others who may find themselves in a similar situation. Society is bred to think that people can’t talk about their sadness, slumps and struggles, and the family sees their openness following Tran’s death as an opportunity for preventing further tragedies and keep the mental health conversation going.

“For others, how many of them didn’t have that opportunity to have this sort of outlet?” Angela Tran asked. “To be given that opportunity to make a positive change, why wouldn’t we take it?”

“We want to bring something positive to his death,” Vanlee Roblee added. “We want to honour him.”

While Tran didn’t seek help from his friends, he always offered his assistance to them.

When Students’ Union Vice-President (Student Life) Vivian Kwan ran in the SU elections last year, none of her volunteers showed up one day — except Tran. He taped Kwan’s posters to billboards, approached random students to give them her flyers and vouched for her support on social media. He even reminded her to eat three times a day, as appetites tend to get lost on the campaign trail.

“He was like, ‘Hey, just let me know what you need and I’ll do it for you,’” Kwan recalled. “And then he just started taking up duties.

“It was just really heartwarming. I could never forget that.”

Kwan was eventually elected with Tran’s help. One of the most prevalent items in the Student Life portfolio is mental health. Kwan admits that mental health initiatives are long-term projects, but Tran’s death and his family’s willingness to be open about preventing future suicides could create the awareness that these battles need right now.

Tran knew about the mental health services offered on campus and used them. Kwan wants to implement an evaluation process on the services to see how the SU and university can improve each area.

“Clearly, for Evan, he used the services, but what’s missing?” Kwan asked. “We don’t know, so hopefully we can start working and see what we can do better. If we have more students equipped with skills to identify crises, that might be a great help.

“Evan was always smiling, but you never know what’s really underneath and inside.”

Tran was afraid of being judged and criticized, which is why he was afraid to reach out. His family want to learn what others can take with them as tools, his cousin Cindy Lu said.

“We want to take away the stigma from mental health and suicide,” Lu said. “It does happen. It’s a real disease, and it’s not an easy fix.”

Dean of Students Robin Everall called Tran’s family. The family made it known that they were using his suicide as a learning experience, and Everall told them that was why she requested to meet with them as well.

The university can appear “cold” and “institutional” when it comes to tragedy, but suicides impact Everall and the U of A deeply, she said. Tran was well known by the Dean of Students office as he volunteered for their mental health initiatives. He was a moderator for the University of Alberta Compliments website and had undergone mental health assistance training. But even then, he didn’t get the help he needed. What mental health services work for others didn’t work for Tran.

“Post-secondary institutions are all challenged not only in how to provide those mental health services, but in helping people reach out to them when they need to,” she said. “That’s sometimes a harder piece than having the services available. What we need to help message is to say, ‘We all struggle.’ There’s no shame in reaching out when you struggle. So when you struggle, this is what we have to offer you. Please use it.”

That’s why a large crowd is expected at a campus memorial for Evan on Wednesday, Oct. 21 at Dinwoodie Lounge from 6 to 9 p.m.

One of the speakers at the event is Tran’s close friend, William Lau.

Tran’s reach on campus went beyond volunteering. He was elected as a representative on the university’s Students’ Council and General Faculties Council. He was also an active participant in various student groups, including the Stollery Youth Committee, where he met Lau.

Lau felt an instant connection to Tran. They clicked right away, as they both were at an event to take photos, had wide-framed glasses and spoke Chinese. Both of them are also known for their dual radiant smiles.

“If I had to describe his role on campus, he would be a servant leader,” Lau said. “He always put others first, and was extremely humble. He put this heart into making things better for other people and was a real giver. He’d just be there for others.”

His viewing (Saturday, Oct. 24 from 6 to 9 p.m.) and funeral service (Sunday, Oct. 25 at 11 a.m.) at Connelly-McKinley Funeral Homes are also expected to be overcapacity, Tran’s brother-in-law Colin Roblee said.

Tran wanted to improve other’s mental health through his actions on campus. When those at the viewing and funeral reminisce on Tran’s life, Roblee hopes the suicide doesn’t sully his memory.

“We want to change people’s perceptions. We don’t want people to think he took the easy way out,” he said.

For Vanlee Roblee, she’ll never forget being in the emergency room when Tran was born. She even named him. Evan meant “little warrior.”

Tran may have lost his fight with depression, but his sister Angela Tran said she thinks he would be proud to see what he’s done to create awareness on the issue of mental health. He never wanted to inconvenience anyone, so he might feel conflicted with the impact he’s made, just might surprise him, and even make him smile.

“He was a complex individual and had these two lives,” she said. “I want these two lives to coincide. I want people to understand that you have your good side, but you have your warts as well. That’s what makes a person a person. I always saw him when he was happy. As much as he was capable of joy, he was also capable of extreme sadness. It’s OK to be open and have both sides.”