Edmonton International Film Festival reviews

Screenshot

ScreenshotVeteran and Beginner filmmakers alike come together as the Edmonton International Film Festival kicks off. EIFF showcases the independent works of these artists. Festival goers learn about the film community and can potentially discover hidden gems. The Gateway looked at a few of the films playing at the festival this weekend. All films can be seen at Landmark Cinemas 9 City Centre. More information can be found at www.edmontonfilmfest.com.

Borealis

Directed by Sean Garrity

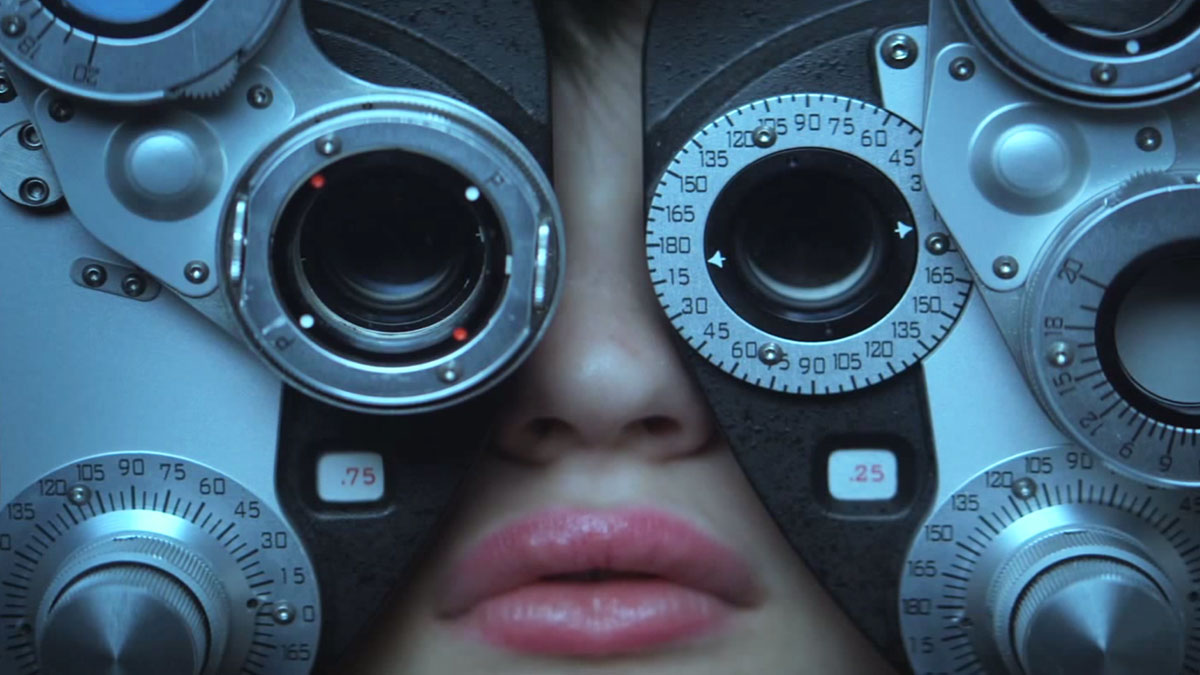

The synopsis of Borealis was intriguing: a dysfunctional father/daughter relationship (the father with a gambling addiction, the daughter about to lose her vision) and a road trip to see the Northern Lights were all qualities that grabbed my attention. The first twenty minutes of the film are appealing as the audience is introduced to the characters, however once it becomes apparent that there isn’t much past what we’ve been introduced to, Borealis loses some serious momentum. It would have been nice to see that Jonah, an unemployed single father with a gambling problem, have more to him than being an unreliable dope, but his character doesn’t really show anything beyond this. Same goes for his daughter, Aurora; despite being about to lose her sight forever, she acts the way pretty much all angsty teenagers do, regardless of being legally blind or not.

Although the storyline is interesting, the delivery just did not meet expectations. What could have been a profound, sentimental piece on beauty, loss (the difference between controllable loss and fated loss) and love, the film simply had a hard time surpassing lines of superficiality. The script was average, with a few admirable lines (mostly coming from Aurora), but the cinematography was pretty good. There were a number of scenes and shots that were quite striking, particularly the ones in which Aurora’s vision is demonstrated for the audience. Of course, the filming was done in Manitoba, which awards the crew some bonus points: anybody who could make Manitoba look interesting is pretty good. Borealis is about on par with what you might think of when someone mentions a road trip through Canada’s forgotten province—stark, tedious and somewhat lackluster. The film definitely captures the chilly temperatures of Churchill, but the warmth promised from the father/daughter relationship is unfortunately lost. — Rachael Phillips

Eadweard

Directed by Kyle Rideout

Eadweard is a psychological drama that follows the career of Eadweard Muybridge, iconic 19th century photographer whose goal for science and art was to document motion — inadvertently inventing the motion picture. His goal, which is realized with greater and greater intensity as the project progresses, is to document motion. Eadweard begins by photographing animals walking, and soon moves to humans, and then naked humans, to capture every angle. Eventually, he moves on to recording deformed subjects. The intensity of Eadweard’s photography evolves parallel to the relationship between he and his wife, Flora, which culminates in the photographer becoming the last person in the United States to be acquitted of for murder with the verdict of “justifiable homicide.”

Visually, the film is clean and colourful, giving the motion picture an element of liveliness that Eadweard himself was unable to capture in the 1890s. The pace of the plot slowly meanders with Eadweard’s development as a photographer, but not in a bad way — this lack of speed is made up for by the movement on screen. Like Eadweard’s own work, the film makes a priority of capturing the motion of its subjects, which engage the viewer.

In terms of psychological development, the film’s focus on Eadweard allows the viewer to experience his increasing difficulty with his interpersonal relationships as he becomes more and more dedicated to his photography. Tensions between he and his wife are never out of control to the point of violence, but their enthusiasm for each other fluctuates over time.

Overall, the film was slow but the visual elements made it into a nice visual experience that gives the viewer a better idea of who the inventor of film really was. — Jamie Sarkonak

Station to Station

Directed by Doug Aitken

Station to Station opens with the promise that the viewer will see one train travel over 4000 miles from coast to coast across the U.S. We are promised an art fueled extravaganza where 10 different creative teams take control of the train, with a huge “Happening” occurring at each station the train stops at. With gorgeous shots of the American countryside or a train covered in neon lights shooting through the night, it’s a visually striking piece.

Each “Happening” is essentially a new art medium performed at a station, or aboard the train. The “Happenings” are each shown in a minute-long short, which either details a short film of an art installation, a minute-long musical performance, or an artist describing their medium.

The most visually interesting parts of the film are the clips where an artist has a chance to show off a huge piece they have created for this project. Some are stationary at a station, like “Smoke Bombs,” where an artist has put together colourful smoke in a gorgeous display. Others play off the moving train for inspiration, like the “Happening” where the artist uses a series of lasers to trace the path of the train. The art interspersed with shots of gorgeous scenery is a treat for the eyes.

There is a lot of music throughout the film, with acts like Ariel Pink and Cold Cave performing on the train while others like Beck and Savages perform on a stage. The music parts are bland compared to the cinematic art shots – one minute of a Dan Deacon concert is boring compared to the artful cinematography making quiet middle-American towns seem beautiful.

If you’re aching to see quick shots of gorgeous countryside, Station to Station is worth a watch. The musical interludes can seem unnecessary at times, but the cinematography and the beautiful representation of art on the screen more than makes up for them. — Kieran Chrysler