Homo naledi bones raise old questions about human nature

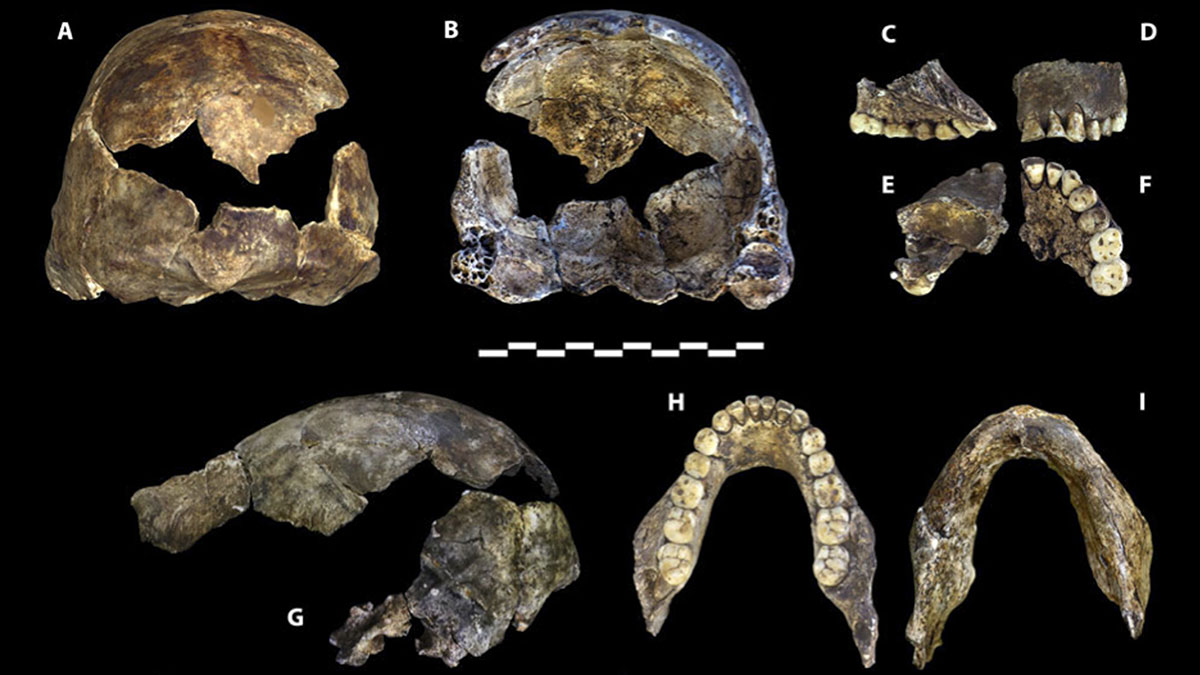

Supplied – Berger et al

Supplied – Berger et alScientists have unearthed, yet again, glowing insights into the human condition. In this case, a new species of human has been discovered, bearing even more knowledge as gifts to our wonderfully adorned, human throne atop Olympus. We call this new species “Homo naledi.”

What’s so special about this discovery? Homo naledi supposedly “bridges the evolutionary gap” between primates and ourselves. More significantly, though, Homo naledi were apparently capable of symbolic thought, made clear by their being found in a ceremonial tomb. Combined this fact with the first, and this new species becomes important; scientists have, until now, thought that only we, Homo sapiens, are equipped to think symbolically. It appears that this “x-factor” we all have — separating us from “animals”— doesn’t actually count as unique. Being human looks more and more like being animal.

I’m almost always for views that refuse to privilege humans above the rest of existence. In sum, we all need to realize that being human-centric has cost us lives and, at this rate, a planet — indeed, a home, a family. Why I’m not over the top about the discovery of Homo naledi, though, is because “gaining” knowledge is strictly not the way out of human-centrism. In fact, it pushes us the other way.

This claim will need to be qualified, of course. But let’s start here.

Naturally, scientists think that the discovery of Homo naledi poses deep questions about human nature. It strikes me as weird that we needed to discover really old bones in order to ponder these sorts of things culturally — even legitimately, for most people. My specific point here is two-fold: on the one hand, we needed scientific knowledge to even consider (again, culturally or “legitimately”) that humans aren’t the centre of the world and endowed with godly gifts; on the other, this knowledge itself is tricky, for reasons owing to thinkers writing roughly two-thousand years ago.

To elaborate, then: doubtless, we are thought to be different than other animals by virtue of our superior intellect. We come to know things about the world, and this is what makes us special. It thus becomes apparent why knowledge doesn’t really help demote humans from the top of natural hierarchy: this is what puts us there in the first place.

You might say: but isn’t knowledge now leading us to justify your desired natural egalitarianism?

Knowledge is generally considered to be “justified true belief”. When you have justification for beliefs that are indeed true, you have knowledge. The catch is, we only have access to the “justified” part of this equation. The ancients, for example, mathematically justified the claim that the sun travels around the Earth; of course, they couldn’t possibly verify the truth of their claim, but it was nonetheless knowledge.

In the same way, we are now (presumably) justified in thinking that we don’t have a fundamental human “x-factor.” But do we actually have access to the truth of this? We are simply justified.

My view, then, is this. Rather than relying on “knowledge” to contemplate the so called “deep questions,” we should rely on a humility that runs deeper than readily admitting that humans aren’t what we thought. We should be humble enough to say: the question of human nature is open, and at best we can love the pursuit of answers to it. We can only approach knowledge. This is different than saying “humans don’t have essential, special nature.” I’m saying that we must humbly keep the question open.

To be sure, rather than know the world, we do things in it; indeed, we can become good at doing things. We become good at building, manipulating, in the same way one becomes good at a sport. The utmost important thing, though, is that “knowledge” is therefore a tool: realizing this amounts to realizing that knowledge need not be a weapon aimed at our home in the name of human well being.